You Know Who Else Besides Humans Are Dangerous to Loons? Loons!

The birds’ own aggressive nature means that even without human interference, their populations face stress from within.

Few birding experiences rival hearing the haunting call of the loon or seeing them glide by in protected coves on a lake. For the birds’ protection, Vermont Fish and Wildlife is asking boaters and anglers to enjoy loons from a safe distance this summer, and take precautions to keep them healthy. With their striking black-and-white plumage and ruby-red eyes, loons are a symbol of wild beauty, gliding gracefully in protected coves.

But beneath this serene image lies a surprising truth: loons can be their own worst enemies. As we work to protect these iconic birds from human threats, their fierce territorial battles reveal another reason they need our help—they’re remarkably tough on each other.

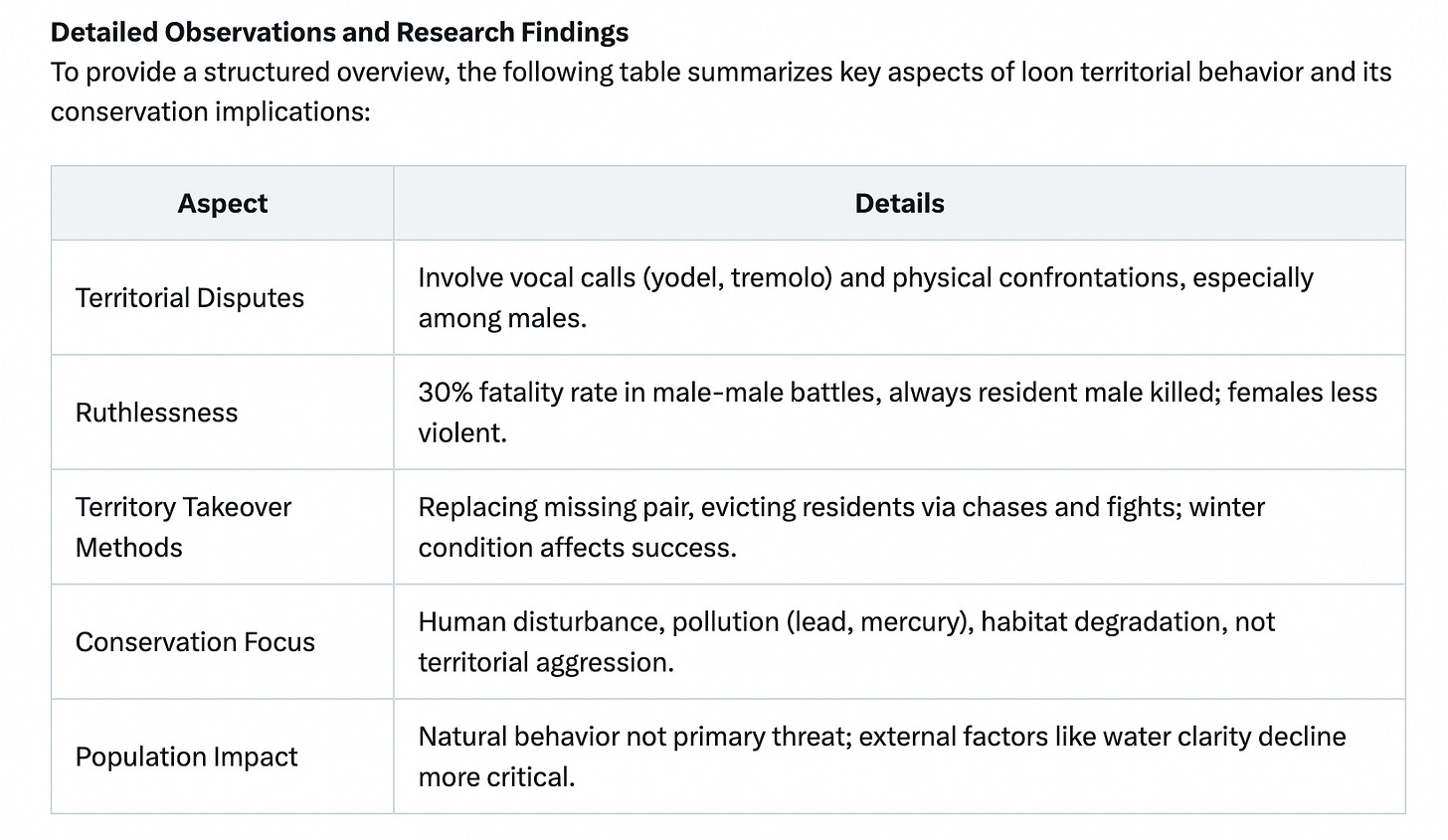

Loons, scientifically known as Gavia immer, are highly territorial, especially during the breeding season from spring to summer. Male loons stake out prime lake territories for nesting and raising chicks, defending them with a distinctive yodel call that signals ownership. When an intruder—often a young or displaced male—challenges for control, things can turn brutal. Research from The Loon Project shows that about 30% of these male territorial battles end in death, with the resident male always the one killed. These fights involve aggressive chases, wing flapping, and sharp pecks with strong beaks, sometimes leading to fatal injuries. Females, while less violent, also displace each other, often forcing the loser to seek a new lake.

“It’s a stark reminder of how high the stakes are for loons,” says Eric Hanson, a biologist with the Vermont Loon Conservation Project. “These battles are natural, but they can take a toll on individuals, especially in areas with intense competition for good nesting sites.” The ruthlessness doesn’t stop at eviction—older males, nearing the end of their breeding years, ramp up their aggression, fighting harder to hold their ground in what researchers call a “terminal investment” strategy.

This internal conflict adds a layer of complexity to loon conservation. Human activities, like boating too close to nests or using lead fishing tackle, are well-known threats. Vermont banned lead sinkers under one-half ounce to curb lead poisoning, which kills loons annually, and the Vermont Loon Conservation Project places collection tubes at boat launches to safely dispose of harmful gear.

Motorboat wakes can flood shoreline nests, and shoreline development degrades the shrubby habitats loons need. But the birds’ own aggressive nature means that even without human interference, their populations face stress from within.

Despite their fierce behavior, loons remain vital to our ecosystems and deserve our care. They’re top predators in aquatic food chains, controlling fish and insect populations, which helps maintain healthy lakes. Their presence is a sign of clean water and intact habitats, benefiting countless other species.

And let’s not overlook their beauty—those sleek dives and soulful calls are a gift to anyone lucky enough to witness them. “Loons are tough, but they’re not invincible,” says Jillian Kilborn, a wildlife biologist with Vermont Fish and Wildlife. “We need to give them space to thrive, both from us and, in a way, from themselves.”

Conservation efforts are making a difference. Volunteers monitor loon pairs through the Vermont Loon Conservation Project, and events like LoonCount Day on July 19 help track populations. Boaters are urged to obey “no wake” zones within 200 feet of shorelines, and anglers are asked to reel in lines when loons dive nearby to prevent entanglements. Shoreline property owners can help by maintaining natural vegetation instead of lawns, creating safe nesting areas.

Loons may be their own adversaries in the fight for territory, but that’s no reason to love them any less. Their competitive spirit is part of what makes them remarkable, a testament to their drive to survive in a challenging world. By protecting them from human threats, we give these beautiful birds a chance to navigate their own battles and continue gracing our lakes with their presence. So, the next time you hear a loon’s call, take a moment to appreciate its wild heart—and keep your distance to ensure it keeps beating.

For more information or to volunteer, contact the Vermont Loon Conservation Project at loon@vtecostudies.org.