Winter 2025-2026: Vermont Readies for a Major Influx of Northern Finches

Ornithologists call this phenomenon an "irruption"—an irregular, mass migration of boreal birds driven south by food scarcity in their Canadian forest home.

Every few years, backyard birdwatchers across Vermont experience something unusual: their feeders suddenly attract waves of unfamiliar, brightly colored birds from the far north. Ornithologists call this phenomenon an “irruption”—an irregular, mass migration of boreal birds driven south by food scarcity in their Canadian forest home.

Unlike familiar spring and fall migrants such as warblers, which travel on a predictable schedule based on day length and hormones, irruptive finches operate on a different logic: they stay put in the boreal forest as long as there’s enough food to survive the winter. When seed crops fail, they move. The Finch Research Network (FiRN), a collaboration of scientists and birders who monitor these movements, has confirmed that conditions are ripe for a significant irruption into New England this winter.

The Northern Story: Why Birds Are Leaving Canada

The driving force behind this year’s irruption is a widespread failure of key food sources across eastern Canada. According to FiRN’s 2025-2026 Winter Finch Forecast Update, seed crops for white spruce and white birch—staples for many finch species—are rated “very poor” across a vast stretch from central Quebec to Manitoba. Mountain ash berries, a critical food source for fruit-eating species like Pine Grosbeaks, are similarly sparse.

Early warning signs appeared as far back as August, when Red-breasted Nuthatches—often considered a bellwether species for irruptions—began appearing south of their normal range. Some were reported as far as the Gulf Coast of Alabama, according to the Valley Forge Audubon Society. When these scouts move early, researchers say, bigger flocks typically follow.

Adding to the picture, widely distributed Spruce Budworm outbreaks in eastern Canada this past summer provided a feast of protein for nesting finches, leading to high survival rates among young birds. The result: larger-than-usual populations of finches are now competing for a smaller-than-usual food supply, intensifying the pressure to head south.

Vermont’s Mixed Picture: Not Quite a Bonanza

While conditions in Canada are clearly pushing birds south, the question of whether Vermont will host massive flocks depends on what food awaits them here. Regional forecasts have been somewhat optimistic, suggesting that cone crops from the Adirondacks through New England are above average this year. However, local authorities offer a more nuanced view.

Kent McFarland of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE) predicts that irruptions in New England may actually be “subdued” this year. The reason centers on one tree: Eastern White Pine. Last winter saw a bumper crop of white pine cones, which attracted significant numbers of Red Crossbills to Vermont. Following that abundance, the white pine crop is “largely absent” this season, according to VCE.

This creates a mixed picture. Birds that rely on spruce and other conifers may find adequate food here. But Red Crossbills—among the most striking of the irruptive finches, with their uniquely twisted bills adapted for prying open cones—are unlikely to linger in Vermont in large numbers. Instead, they may bypass the state entirely in search of better foraging elsewhere.

Some early forecasts compared this year’s potential to the “Superflight” of 2020-2021, which was one of the most dramatic irruptions in memory. That event was driven by a rare perfect storm: total crop failure in the north and bumper crops throughout the south. Experts suggest 2025-2026 may fall short of that benchmark, but it should still be a noteworthy year for finch diversity in Vermont.

What Birds to Watch For

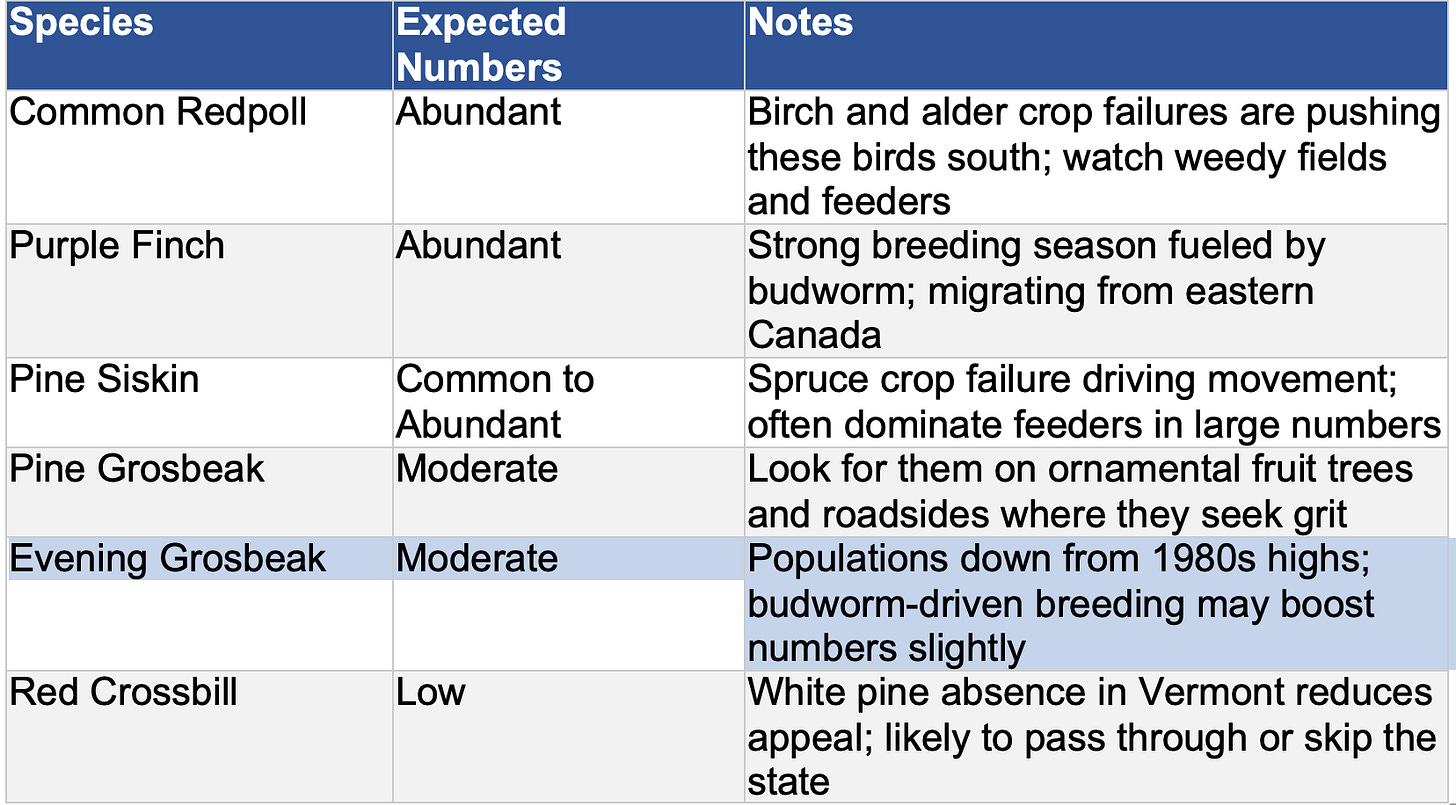

Based on current forecasts, here is what Vermont birdwatchers might expect this winter:

A Note on Redpolls and Recent Taxonomy Changes

Longtime birders may recall distinguishing between Common Redpolls and the rarer, paler Hoary Redpolls. In 2024, the American Ornithological Society officially lumped these into a single species, now simply called “Redpoll.” Research found that the plumage differences are controlled by a “supergene” affecting coloration—similar to how eye color works in humans—rather than indicating separate species. Nevertheless, spotting the frosty, pale “Hoary” variant remains a rewarding challenge when scanning large flocks, according to FiRN’s forecast.

Telling Purple Finches from House Finches

With Purple Finches expected to arrive in force, confusion with the year-round resident House Finch is inevitable. The legendary field guide author Roger Tory Peterson offered a memorable way to tell them apart: a male Purple Finch looks like a “sparrow dipped in raspberry juice,” with the rosy color washing over its back and wings, while a House Finch appears “streaked with brown,” with the red confined mostly to its brow and breast. Consult Birds Outside My Window for more identification tips.

Before You Fill Your Feeders: Safety Considerations

Black Bears and the December 1st Guideline

Vermont’s Black Bear population remains active well into late fall, and bird feeders are the most common source of human-bear conflicts in the state. The Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department advises residents to wait until December 1st—or until there is persistent snow cover and bears have denned—before putting out feeders.

Climate trends have shortened the hibernation window for Vermont bears, with many emerging earlier in spring and denning later in winter, according to Valley News reporting. Intentionally feeding bears is illegal in Vermont, and leaving out attractants like bird feeders once a bear has become habituated can result in the animal being destroyed. Wildlife officials often summarize the risk starkly: “A fed bear is a dead bear.”

Feeder Hygiene and Disease Prevention

Large congregations of birds at feeders create opportunities for disease transmission. Pine Siskins, one of the species expected in abundance this winter, are particularly susceptible to Salmonella. Outbreaks can cause significant die-offs when fecal matter accumulates at heavily used feeding stations.

The Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department recommends cleaning feeders every two weeks with a 10% bleach solution (one part bleach to nine parts water), rinsing thoroughly, and allowing them to dry completely before refilling.

Concerns about Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (H5N1) have prompted questions about feeder safety. While songbirds are less susceptible than waterfowl, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology notes that transmission at feeders is possible. Regular cleaning and monitoring for any signs of sick birds remain prudent practices.

What Happens Next

The coming weeks will reveal how this winter’s irruption unfolds. Redpolls and Pine Siskins are typically among the first to arrive in numbers, often appearing at thistle feeders and in weedy fields. Pine Grosbeaks tend to linger around ornamental crabapple and mountain ash trees in suburban areas, while Purple Finches gravitate toward sunflower feeders.

Birdwatchers can contribute to scientific understanding by reporting sightings through platforms like eBird, which helps researchers track the timing and extent of irruptive movements. The Finch Research Network will continue to update its forecasts as the season progresses.

For Vermonters eager to welcome these northern visitors, the key is patience: wait for true winter conditions, keep feeders clean, and be ready to encounter birds that may not appear again for years. Even if 2025-2026 falls short of a historic superflight, it promises to be a season of colorful visitors and unusual sightings—a reminder of Vermont’s connection to the vast boreal forests to the north.