Why Wagyu, and Why in Vermont? Here's the Beef

Terroir (natural environment) is a cornerstone of the wine world. A growing number of farmers and chefs argue it's just as crucial for raising meat, and Vermont is seen as ideal.

A new label appearing on packages of beef from a Springfield farm is shining a spotlight on a small but growing corner of Vermont's agricultural landscape. The farm, Vermont Wagyu, recently announced it would be the first in the nation to use the "Certified Authentic Wagyu" mark, a new program from the American Wagyu Association (AWA) that is certified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The move signals a coming-of-age for American-raised Wagyu, a type of beef renowned for its tenderness and intricate marbling. But it also raises a deeper question: in a state famous for its dairy cows, cheddar cheese, and maple syrup, why is this luxury Japanese beef finding such a successful home here? The answer may lie in a concept most often associated with fine wine: terroir.

First, What Exactly is Wagyu?

The term Wagyu (和牛) literally translates to "Japanese cow." It refers to specific breeds of cattle genetically predisposed to intense fat marbling. This isn't the thick cap of fat you might trim off a steak, but rather delicate, intramuscular fat that riddles the muscle tissue. When cooked, this fat melts, creating a rich, buttery flavor and a texture so tender it can, as a common saying goes, be cut with a fork.

This unique marbling is a result of a higher concentration of monounsaturated fats, particularly oleic acid—the same "good fat" found in olive oil. According to nutritional studies, this profile means Wagyu fat has a lower melting point than typical beef fat, contributing to its signature melt-in-your-mouth quality.

Raising these animals is a long and meticulous process. Unlike conventional beef cattle, which are typically raised for 15 to 18 months, Wagyu cattle can be raised for up to 30 months or more. This extended timeline, combined with specialized diets and careful animal husbandry, allows the distinctive marbling to fully develop.

The Argument for Vermont's Terroir

Terroir is the idea that the unique environment of a place—its climate, soil, and topography—imparts a distinct character to an agricultural product. While it's a cornerstone of the wine world, a growing number of farmers and chefs argue it's just as crucial for raising meat. For Vermont's Wagyu producers, the state’s environment isn't just a backdrop; it’s a key ingredient.

Proponents believe several factors make Vermont's terroir uniquely suited for producing world-class Wagyu:

Climate and Comfort: Wagyu cattle are naturally hardy, with a thick hide that prepares them for harsh conditions. It's argued that Vermont's four distinct seasons, especially its cold winters and temperate summers, create a less stressful environment than perpetually hot climates. A low-stress life is considered essential for developing the highest quality meat, as stress hormones like cortisol can negatively impact muscle tissue.

Superior Forage: The quality of a cow's diet is directly reflected in the quality of its meat. Vermont's nutrient-rich soil, ample rainfall, and rolling pastures produce exceptionally lush grasses and hay. This high-quality forage forms the foundation of the cattle's diet, contributing to the nuanced flavor of the finished beef.

Purity of Resources: Clean air and cold, fresh water are hallmarks of Vermont's landscape. Just as with humans, pure water is essential for an animal's health and development, and local producers point to this as a critical, if often overlooked, element of their success.

While cattle ranchers in other states like Texas or Washington would make strong cases for their own unique terroir, the combination of Vermont’s climate, water, and forage creates a compelling argument for its place as a premier region for raising Wagyu in the United States.

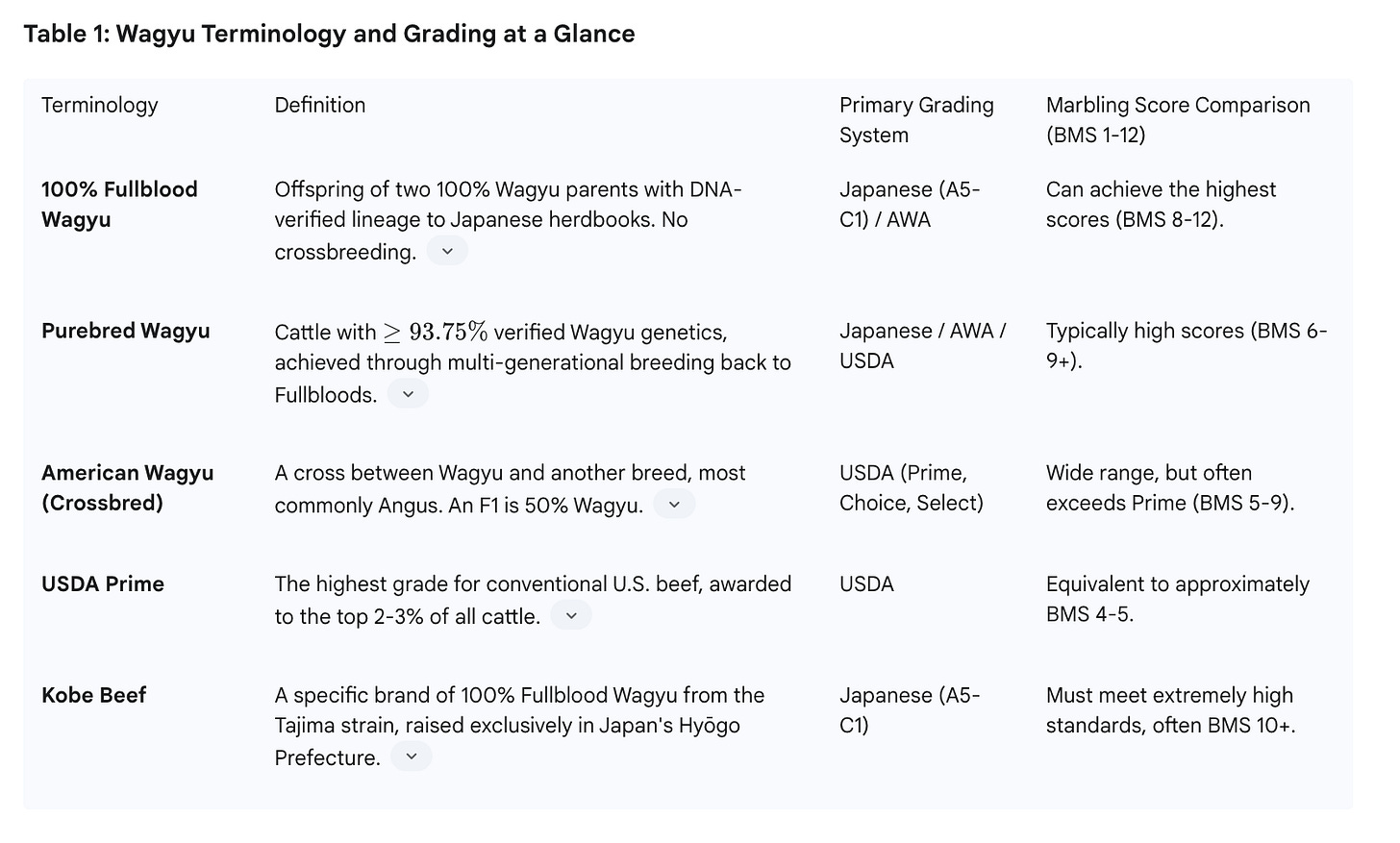

A Cut Above Prime

For years, American beef producers have used the USDA's grading scale—Select, Choice, and Prime—to signify quality. Prime is the highest grade, awarded to beef with the most marbling. However, producers of American Wagyu have long argued that their best products far exceed the minimum standards for a Prime rating.

Japan has its own, more granular system, which grades beef on a scale from 1 to 5, with A5 representing the pinnacle of quality. The new "Certified Authentic Wagyu" label is the American industry's answer to this gap. According to the American Wagyu Association, the program was created to give consumers confidence that they are buying genuine Wagyu with a marbling level that qualifies as being at the high end of the USDA Prime grade.

Sheila Patinkin, owner of Vermont Wagyu and the former AWA board president who, according to the press release, spearheaded the committee for the new label, says the program is vital. "By looking for the Certified Authentic Wagyu label," she stated in the release, "consumers, restaurants, and food service workers alike can now identify the quality of their beef with confidence."

The Vermont Connection

The presence of a farm like Vermont Wagyu, and others in the state like Morgan Brook Farm in Westford and Sheldon Creek Farms in Pawlet, is no accident. The Green Mountain State's agricultural identity has increasingly been defined by high-quality, artisanal products with a strong sense of place. Just as consumers seek out Vermont-made cheeses, craft beers, and spirits, a market has emerged for locally raised, premium meats.

This farm-to-table ethos, deeply embedded in the state's culinary scene, creates a demand that a handful of local farmers are now meeting. Restaurants from Burlington to Manchester feature Wagyu on their menus, often as a premium "Wagyu burger," signaling a willingness among Vermont diners to pay for a superior product with a local story. These Vermont farms are not large-scale operations; they are typically family-run, fitting into the state's pastoral landscape of smaller, specialized agriculture.

The numbers show just how specialized this niche is. According to data from the American Wagyu Association, 100% Fullblood Wagyu—animals with a direct, un-crossed lineage to Japanese herds—make up a minuscule fraction of the total U.S. cattle population, somewhere around 0.016%.

Is It Worth It?

The primary barrier for most consumers is, unsurprisingly, the price. Wagyu steaks can cost several times more per pound than even a high-end cut from a conventional breed. The cost is a direct reflection of the investment required: the expensive genetics, the longer lifespan of the animal, and the superior terroir and feed.

For those who do indulge, the experience is often seen as more of a delicacy than a typical steak dinner. The richness of the meat means portion sizes are often smaller. Proponents point to its unique flavor and texture as an unparalleled culinary experience. They also note the potential health benefits of its fat profile, which is higher in beneficial monounsaturated fats compared to other red meats.

Ultimately, the rise of Wagyu in Vermont is another chapter in the story of the state's agricultural evolution. It reflects a modern food culture that values not just sustenance, but quality, craftsmanship, and the unique taste of a place—the terroir—where the food was raised.