Why the First Flakes of Vermont Snow Are the Dirtiest: Lessons from Winter Storm Fern

Winter Storm Fern dumped up to 18 inches on Vermont last month. State environmental data shows that not all of that snow is equally safe to consume.

A Massive Storm Creates a Natural Experiment

Winter Storm Fern swept across Vermont between January 23 and January 27, 2026, bringing 8 to 18 inches of snow to different parts of the state. The storm originated from an atmospheric river from the Pacific that merged with Gulf of Mexico moisture before transitioning into a powerful nor’easter. The preceding arctic front created wind chills that dropped below zero, setting up conditions that would determine the chemical composition of the snowfall.

The storm created what scientists view as a large-scale case study in atmospheric chemistry and public health—one that reveals how Vermont’s winter precipitation acts as an efficient filter for airborne pollutants.

Why Snow Acts as Nature’s Air Filter

Freshly fallen snow may look pristine, but from a scientific perspective, it functions as what researchers call an “atmospheric scrubbing” mechanism. The complex, branching geometry of snowflakes—specifically their high surface-area-to-mass ratio—allows them to capture airborne pollutants more effectively than rain.

As Winter Storm Fern moved across the continental United States, it incorporated pollutants from upwind industrial areas, including black carbon from coal-fired plants, nitrogen oxides from transportation corridors, and diverse chemical aerosols. The falling snow acted as a transfer mechanism, moving these contaminants from the atmosphere to the ground.

The Washout Effect: Why Timing Matters

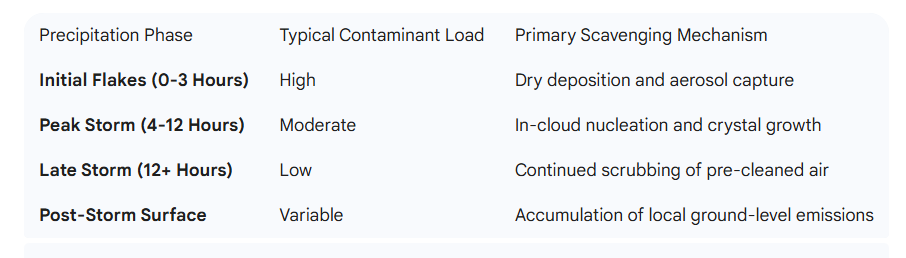

The safety of consuming snow depends fundamentally on when it fell during the storm. Scientific analysis shows a “washout effect” with distinct phases during major winter weather events.

In the initial hours of Winter Storm Fern, the falling snow acted as a primary filter, removing the highest density of suspended particles that had accumulated in the atmosphere during preceding dry periods. This early-stage snow serves as a repository for dust, pollen, soot, and chemical contaminants.

As the storm progressed through January 25 and 26, the atmosphere underwent progressive cleaning. Snow falling several hours into the event typically exhibits lower concentrations of impurities, as the reservoir of airborne pollutants is exhausted. However, even “purified” snow is not sterile—the very nucleus of a snowflake often consists of a microscopic particle of soil, a bacterial cell, or a fungal spore.

The chemical constituents found in Vermont’s snow include sulfates, nitrates, formaldehyde, and mercury, though these are typically present at sub-toxic levels in a single ingestion event. The broader concern arises from cumulative ingestion and the potential for higher concentrations in localized areas.

Burlington and Urban Corridors: Traffic Creates the Biggest Risk

The safety of snow consumption in Vermont varies dramatically by geography, with urban centers like Burlington and the Chittenden County area presenting a distinct risk profile. In these densely populated regions, the primary hazards come from mobile sources—specifically vehicle exhaust and non-tailpipe emissions.

The Emerging Threat of Tire Wear Particles

A significant concern in urban environmental health is the prevalence of non-tailpipe emissions, which include brake dust and tire wear particles. Research indicates that as vehicle exhaust has been reduced through regulation, non-tailpipe emissions have become a dominant source of particulate matter near roadways.

Tire wear particles are a complex mixture of natural and synthetic rubbers, carbon black, silica, sulfur, and various chemical additives. As vehicles navigated the I-89 and I-91 corridors during and after Winter Storm Fern, mechanical abrasion against the road surface released millions of these microscopic fragments, often measuring less than 10 or 2.5 micrometers.

These particles are easily trapped by falling or blowing snow. The concentration of these microplastics and light-absorbing particles is highest within 150 to 500 meters of major highways. Snow collected in urban backyards near high-traffic areas may contain significant quantities of these petroleum-derived contaminants.

Road Salt and Chemical De-Icers

The maintenance of Vermont’s transportation infrastructure during Winter Storm Fern required aggressive application of chemical de-icers. The Vermont Agency of Transportation utilizes a mix of granular sodium chloride, liquid magnesium chloride, and salt brines to lower the freezing point of water on road surfaces.

At the extreme temperatures encountered during the storm, standard salt loses its efficacy, leading to increased use of liquid magnesium chloride, which often contains corrosion inhibitors and proprietary additives. The resulting snowmelt and plow-spray redistribute these chemicals into the adjacent snowpack.

Snow found in roadside embankments or parking lot “snow mountains” is a highly concentrated solution of road salt, automotive oils, gasoline residues, and heavy metals. Ingestion of such snow can cause minor electrolyte imbalances, mouth irritation, or exposure to carcinogenic hydrocarbons.

Valley Communities: Wood Smoke Traps Pollution

In central and southern Vermont, particularly in communities like Rutland and Bennington, the primary threat to snow purity is dictated by topography and residential heating practices. These areas are prone to temperature inversions—a meteorological phenomenon where cold, dense air becomes trapped on the valley floor, capped by warmer air above.

The Wood Smoke Problem

During the frigid week following Winter Storm Fern, residential wood heating was used extensively. Wood smoke is a major source of fine particulate matter in Vermont, often accounting for more than 20% of wintertime particle pollution. Smoke from wood stoves, boilers, and fireplaces contains hundreds of chemical compounds, including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, several of which are known carcinogens.

In Rutland, which sits in a pronounced mountain valley, stagnant air during the post-storm period led to elevated particulate levels, with Air Quality Index readings reaching 71, classified as “Moderate.” The falling snow in these regions effectively “washes” the wood smoke out of the air, trapping black carbon and soot within the snowpack. Consumption of snow with a visible gray or “dingy” tint carries a risk of ingesting concentrated combustion byproducts.

Champlain Valley: Agricultural Chemicals Present Unique Risks

The Champlain Valley, characterized by its fertile land and high density of dairy operations, presents unique environmental risks related to pesticide drift and microbiological contamination.

Pesticide Persistence

While active pesticide application is less common during winter, the environmental persistence of these chemicals in the Champlain Valley is well-documented. A legal challenge in late 2025 targeting the Vorsteveld farm in Panton underscored the presence of toxic herbicides and insecticides in local tributaries at levels significantly exceeding federal safety benchmarks. Chemicals of concern include atrazine, metolachlor, and neonicotinoids like clothianidin.

Atrazine, a known hormone disruptor linked to birth defects and cancers, can move off-target through vapor drift or by adhering to wind-blown soil particles. During the high-wind conditions of Winter Storm Fern, soil and chemical residues from agricultural fields could be incorporated into falling snow. Furthermore, neonicotinoids, though being phased out in Vermont by Act 182, remain persistent in the soil.

Manure Management and Bacteria

Vermont maintains a strict ban on manure spreading between December 15 and April 1 to prevent runoff into frozen or snow-covered waterways. However, the presence of large-scale Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations in the Champlain Valley creates localized risks.

Snow in proximity to manure storage sites or grazing lands can be contaminated with pathogens such as E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Cryptosporidium. Bacteria can survive for extended periods in frozen conditions, and ingestion of snow contaminated with even trace amounts of animal waste can lead to acute gastrointestinal illness, particularly severe in children or immunocompromised individuals.

Northeast Kingdom: The Cleanest Snow, With Caveats

The Northeast Kingdom and higher-elevation areas of the Green Mountains generally provide the safest environment for snow consumption. These regions benefit from lower population densities, fewer major traffic corridors, and less intensive industrial or agricultural activity.

However, even the snow in the NEK is subject to long-range atmospheric transport of pollutants. Studies have shown that microplastics and black carbon can be found in high-elevation snow in the Rocky Mountains and Appalachians, suggesting no region is truly pristine. Furthermore, the prevalence of residential wood heat in the NEK means localized concentrations of smoke can still impact snow quality in rural settlements.

The Physical Risks of Eating Snow

Beyond chemical and biological contaminants, eating snow carries physiological risks amplified by Vermont’s extreme winter conditions.

The Hypothermia Factor

One of the most critical warnings from emergency and wilderness medicine experts is the metabolic cost of melting snow in the mouth. Converting snow from its solid state at zero degrees or colder to liquid water at body temperature requires substantial thermal energy. For a person already exposed to sub-zero temperatures and extreme wind chills, this energy expenditure can lower core body temperature and accelerate the onset of hypothermia.

The Dehydration Paradox

Snow is also a poor source of immediate hydration. Because snow is largely composed of air, the volume required to produce a single liter of water is enormous. The energy required to melt that volume, coupled with potential gastrointestinal irritation from pollutants, can actually lead to a net loss of body fluids. Experts recommend that snow should always be melted using an external heat source and ideally purified before consumption.

The Bottom Line: Geography and Timing Determine Risk

The question of whether it is safe to eat Vermont’s snow after Winter Storm Fern does not yield a simple yes-or-no answer. Instead, it requires an assessment of risk based on multiple environmental factors.

For a healthy individual living in a rural area like the Northeast Kingdom or the upper Green Mountains, consuming a small amount of freshly fallen, mid-storm snow collected from an elevated, clean surface is generally considered a low-risk activity. The concentration of contaminants in such snow is typically far below toxic levels.

However, for individuals in urban centers like Burlington, valley towns like Rutland, or agricultural corridors like the Champlain Valley, the risk profile is significantly elevated. In these regions, snow acts as a delivery system for pollutants—transporting road salt, tire wear microplastics, wood smoke carcinogens, and agricultural chemicals.

The consensus among health experts is that while catching a few snowflakes on the tongue is harmless, using snow as a primary culinary or hydration source should be approached with caution. The “safest” snow in Vermont is found far from roads, chimneys, and farms, collected after the storm’s initial “washout” phase, and consumed sparingly by healthy individuals.

LOL! You forgot about pollutants from Volcanic activity, just saying... And what about the Vermont tradition of "Snow Cones" with Maple syrup?? :)