When Waters Rise, Vermont’s Flood Warning Systems Help—If You’re Connected

The places in Vermont most likely to flood are often the least connected—leaving residents in places with limited or no access to the digital lifelines so many alert systems.

In a state where flash floods can destroy homes, wash out roads, and isolate entire communities in a matter of hours, the ability to receive timely emergency warnings is a matter of life and death. Yet in Vermont, where some of the most flood-prone towns are also digital dead zones, modern flood alert systems built on apps and internet connectivity may fail when they’re needed most.

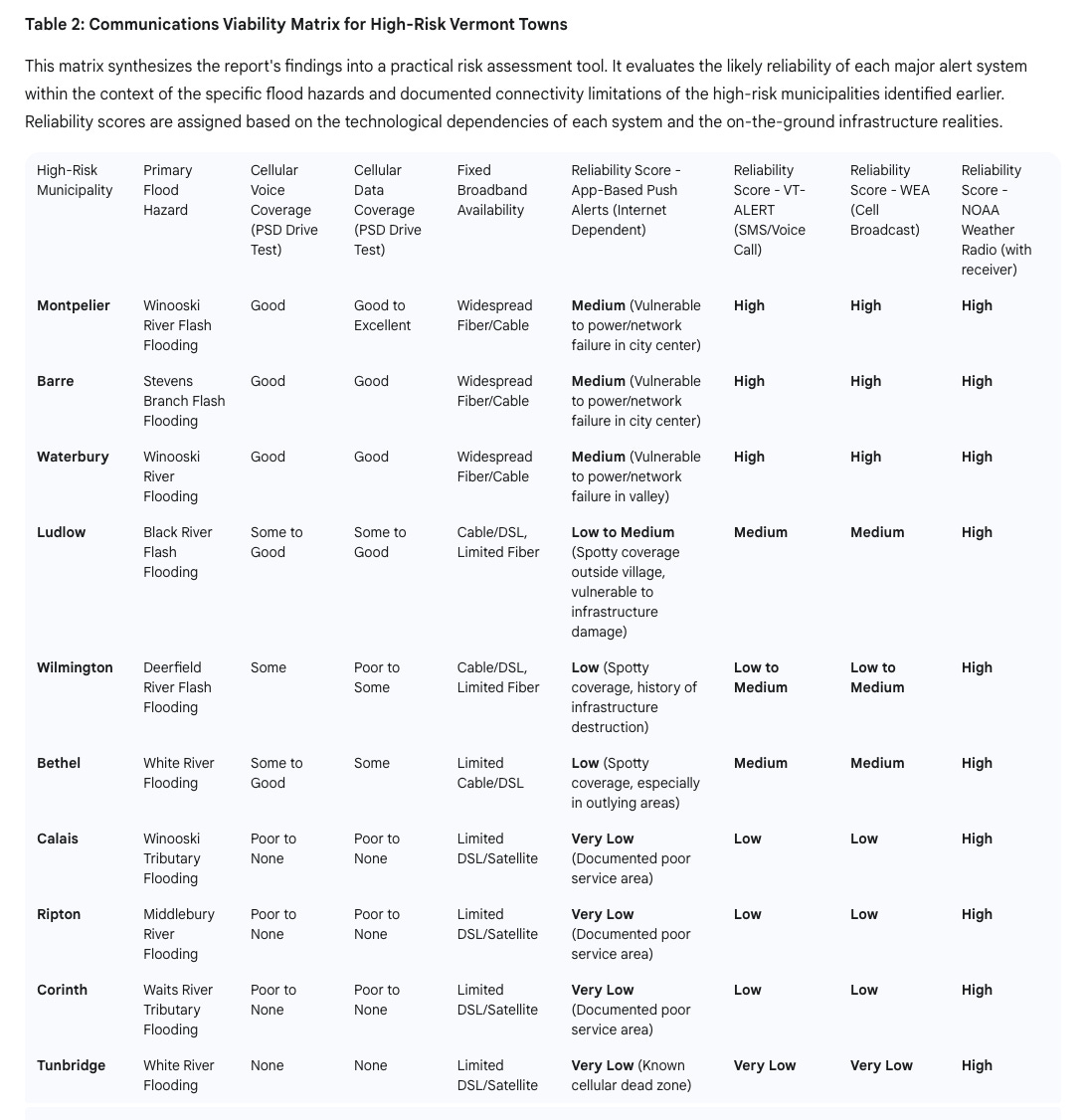

A comprehensive analysis of Vermont’s emergency alert infrastructure reveals that the weakest link in the state’s flood resilience strategy is not the technology itself, but the fragile networks that support it. According to historical accounts, government reports, and data from the Vermont Department of Public Service, the places most likely to flood are often the least connected—leaving residents in places like Tunbridge, Corinth, and Ripton with limited or no access to the digital lifelines so many alert systems depend on.

The App Dilemma: Rich in Data, Poor in Resilience

Applications like RiverAware and FloodAlert have become popular tools for Vermonters seeking real-time flood information. RiverAware, developed in Vermont after Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, offers interactive river maps and alerts pulled from more than 13,000 stream-gauging stations maintained by federal agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey and National Weather Service. As Popular Mechanics reported in 2023, its developer acknowledged “scares” when the app could not pull live data due to cloud delivery issues.

Similarly, FloodAlert markets a paid SMS feature that allows users to receive alerts even without an internet connection—a tacit admission that its standard internet-based push notifications are vulnerable.

These apps “represent the richest and most visually appealing data,” but in the words of a 2023 Vermont Emergency Management analysis, they are also “the most fragile layer in the alert ecosystem.”

When floods wipe out power lines and take down cellular towers, as they did during Tropical Storm Irene and again during the July 2023 floods, home Wi-Fi and mobile data often disappear first. The result? The very tools that people rely on to warn them become useless.

VT-ALERT: Designed for Failure—And Recovery

Vermont’s official warning system, VT-ALERT, was created with these limitations in mind. Operated by Vermont Emergency Management and powered by the Everbridge platform, VT-ALERT is not a standalone app, but a multi-modal notification system that distributes alerts via SMS, email, voice calls (including landlines), and mobile app notifications.

According to the Vermont Emergency Management 2023 Annual Report, the strength of VT-ALERT lies in its redundancy. If an alert can’t be delivered over the internet, it might still be received by a traditional copper landline—which, unlike VoIP services, often stays powered during outages. VT-ALERT can also initiate “Reverse 911” calls to all landlines in an affected area, whether or not those residents registered for the system.

Still, this system isn’t foolproof. It depends on the reliability of cell towers, landlines, and power grids that may all be compromised during a major flood. And in many parts of rural Vermont, those systems are weak even in good weather.

The Tunbridge Example: When Apps Are a Fantasy

Nowhere is the danger of overreliance on digital alerts more apparent than in Tunbridge. This Orange County town, tucked in the White River watershed, is a known “cellular dead zone,” according to Seven Days reporting from 2023. For roughly 10 miles in either direction, cell service is nonexistent.

To address the gap, a local engineer installed internet-powered payphones in North Tunbridge—currently the only reliable public communication infrastructure. That measure, while clever, illustrates a grim reality: in a disaster, neither apps nor texts nor calls are likely to reach residents in time.

Tunbridge is not alone. The towns of Corinth, Ripton, Calais, and parts of the Mad River Valley have been flagged by the Vermont Department of Public Service as having little to no mobile coverage. These same areas—steep, forested, and hard to access—are also among the most vulnerable to flash flooding, as documented by the state’s Flood Ready Atlas and historical FEMA disaster declarations.

Flood Maps and Warning Gaps: A Dangerous Overlap

Data from FEMA and the Vermont Flood Ready Atlas show a pattern: Vermont’s worst floods tend to strike in narrow valleys along rivers like the Winooski, White, Mad, and Otter Creek. The July 2023 flood alone saw 9.2 inches of rain fall on Calais in 48 hours, according to NOAA storm summaries. Towns such as Montpelier, Barre, Ludlow, and Bethel were overwhelmed, many for the second or third time in a generation.

Yet when these maps are overlaid with the Vermont Department of Public Service’s wireless drive test data—a real-world measure of cell signal coverage—a disturbing truth emerges. Many of the state’s most at-risk towns fall into “poor” or “no coverage” zones across all major carriers. This includes not just remote homesteads, but entire communities.

Radios, Landlines, and Redundancy: Vermont’s Best Bet

The state’s emergency planners have long understood this fragility. That’s why the oldest tools remain the most reliable. NOAA Weather Radios, equipped with Specific Area Message Encoding (SAME), are considered the gold standard for alerts. They don’t require the internet or a cell signal, just a battery and a broadcast tower—which the National Weather Service operates in Burlington, Windsor, and St. Johnsbury.

Amateur (HAM) radio is another fallback, used by emergency managers when all else fails. The National Weather Service office in Burlington maintains its own HAM station (WX1BTV), according to NWS Emergency Operations documentation.

Traditional landline phones—connected to copper lines, not internet modems—remain critical. Unlike modern digital services, these lines carry their own power and often remain functional during blackouts.

Conclusion: One Message, Many Paths

The takeaway is clear: flood alerts in Vermont must never rely on a single delivery path. A sleek app may impress in a dry office but will likely fall silent when the water rises.

The state has built a multi-layered system in VT-ALERT, backed by national-level alerts (WEA and EAS), and supported by the analog stalwarts of NOAA radio and landlines. But residents must do their part—by registering for all available VT-ALERT channels, programming a weather radio, and making old-fashioned tools part of their emergency kits.

In flood-prone Vermont, survival may come down to whether the warning gets through. And for many communities still struggling to connect to the digital world, the answer won’t come from an app.