When 'Help Me' Turns to 'Who Is He?': The Vermont Panhandling Post That Went Viral

Some called him a liar. Others suggested compassion. One comment read, “he goes around begging and harassing people for money.” Another, more hostile, said, “A very smackable face.

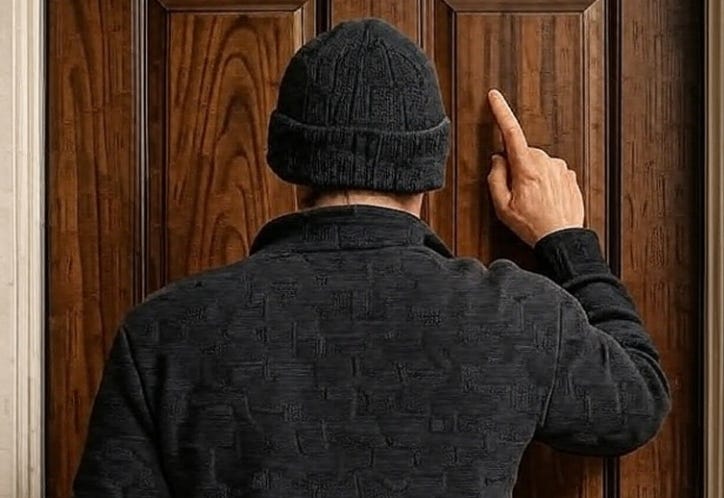

A Knock at the Door

It began with a simple Facebook post from a resident of Bennington:

“Does anyone know who this guy is? He came to my door asking for money. He gave me this sob story that his wife was a two-stage diabetic and he didn’t have any shoes. He said he needed money to pay a gentleman waiting for a ride.”

Within hours, the post drew 139 comments. According to those comments, several residents recognized the man and recounted similar encounters — stories about needing money for bus fare, illness, or a stolen wallet.

Some called him a liar. Others suggested compassion. One comment read, “He’s a local panhandler, he goes around begging and harassing people for money.” Another, more hostile, said, “A very smackable face.”

The discussion quickly became less about one man’s alleged deceit and more about what happens when ordinary people feel they have to fill the void left by limited law enforcement, social services, or mental-health outreach.

The Friction Between Sympathy and Self-Protection

Bennington, like many Vermont towns, has wrestled with how to handle visible poverty and addiction without enough resources to respond to every individual need. According to state social-service data, small communities often have only one or two outreach workers serving multiple towns. Police departments, stretched thin, prioritize violent or ongoing criminal activity — not door-to-door solicitation that falls into a legal gray zone.

As one commenter put it, “Why can’t the cops do something?” Another replied, “Because it’s not illegal to ask for help.”

That tension — between wanting to protect neighbors and fearing being taken advantage of — is central to the Facebook thread’s emotional charge. In less than 24 hours, a neighborhood conversation evolved into a digital jury: assessing guilt, intent, and even the moral worth of the person in question.

When the System Feels Absent

Sociologists describe this type of reaction as “community self-regulation.” When people perceive that official systems have failed — whether in policing, addiction treatment, or housing support — they often turn to informal mechanisms: neighborhood watch pages, social media alerts, and public shaming.

According to University of Vermont social scientist Dr. Kathryn Stam, these digital exchanges often serve as “substitute governance.” People seek to restore control when they feel institutions no longer can. “It’s not just about safety,” she said in a similar study of small-town Facebook groups. “It’s about moral order — defining who belongs and who doesn’t.”

But this form of vigilance can quickly cross into defamation or vigilantism. Vermont law protects individuals from libel and harassment, even online, and local police frequently warn residents that identifying or confronting alleged scammers themselves can escalate conflict or put people at risk.

The Limits of Local Capacity

Bennington’s experience isn’t unique. Across Vermont, towns are confronting the visible effects of homelessness, addiction, and mental-health breakdowns. According to the Agency of Human Services, Vermont’s homeless population has more than doubled since 2020, while federal pandemic relief that once supported emergency housing has largely ended.

Law enforcement leaders acknowledge they are being asked to respond to what are essentially social or medical problems. “Police officers aren’t trained social workers,” one Bennington County official said at a town forum last year. “We can’t arrest our way out of poverty.”

That gap leaves residents in a difficult position. When someone shows up at the door — barefoot, desperate, or possibly manipulative — what is the right thing to do?

What Taking Action Means

Some commenters urged empathy: “If you can, give him socks or food instead of cash.” Others advocated confrontation or posting photos to warn others. The post became a real-time referendum on how a community defines responsibility.

The impulse to “take things into our own hands,” as one person wrote, is understandable — but also fraught. Self-organized responses can strengthen community bonds or harden divisions, depending on whether they lead to compassion or scapegoating.

Public-safety experts emphasize measured engagement. According to Vermont State Police guidance, residents should not post identifiable photos of suspected offenders unless law enforcement requests help locating them. Instead, they recommend reporting suspicious activity through official channels and supporting outreach programs that connect vulnerable individuals with services.

A Broader Reflection

At its core, the Bennington thread is less about one man’s alleged scam than about collective trust. When citizens lose faith that local or state systems can protect, assist, or even acknowledge them, they begin to improvise. Sometimes that improvisation looks like charity; other times, like vigilantism.

The deeper question for Vermont communities is whether these online moments can evolve into something constructive — more funding for social services, coordinated neighborhood watch programs that work with local agencies, or even simple neighbor-to-neighbor understanding.

Until then, Facebook posts like this one will continue to act as digital town meetings — places where Vermonters publicly negotiate the line between compassion and caution, between justice and judgment.

Conclusion: A Test of Community Character

Every town faces the same balancing act: protecting itself without hardening its heart. The Facebook discussion from Bennington reveals both the fatigue and the resilience of small communities trying to fill gaps that government alone cannot fix.

Understanding this tension — between institutional absence and civic response — is essential for Vermont’s path forward. Whether Vermonters choose empathy, organization, or stricter enforcement as their collective answer will shape not only public safety but the moral texture of small-town life itself.

Having grown up in Vermont, the state tends to do better when it finds it's own grassroots solutions for food coops, local shelter options, and housing options for crisis. It seems to me ironic that the people who were most secure were the ones who felt the most threatened. Is the guy a liar? It's possible.. desperate people do desperate things.. does that make this man less human then the members of the Facebook group? If you don't trust the man, at least give him an offer of food and send him on his way.