When Goodwill Runs Out: Could Vermont's Property Tax Crisis Close the Door on $2.1 Billion in Outdoor Recreation?

While Vermont property owners who permit recreational use of their land are legally protected, they receive no compensation or tax relief for their generosity.

Vermont’s outdoor recreation economy—valued at $2.1 billion and representing 4.8% of the state’s entire GDP—rests on an unusual foundation: the unpaid generosity of thousands of private landowners who allow strangers to snowmobile, mountain bike, hike, and hunt across their property.

But as property taxes surge across Vermont, a critical question emerges: is there a breaking point where landowners, facing ever-higher tax bills without any compensation for providing public access, simply say no?

If that happens, the consequences would be swift and catastrophic.

The Permission Economy

Vermont’s recreational infrastructure operates on what analysts call a “permission economy”—a high-trust system built not on permanent public ownership, but on annual handshake agreements between nonprofit trail organizations and private property owners.

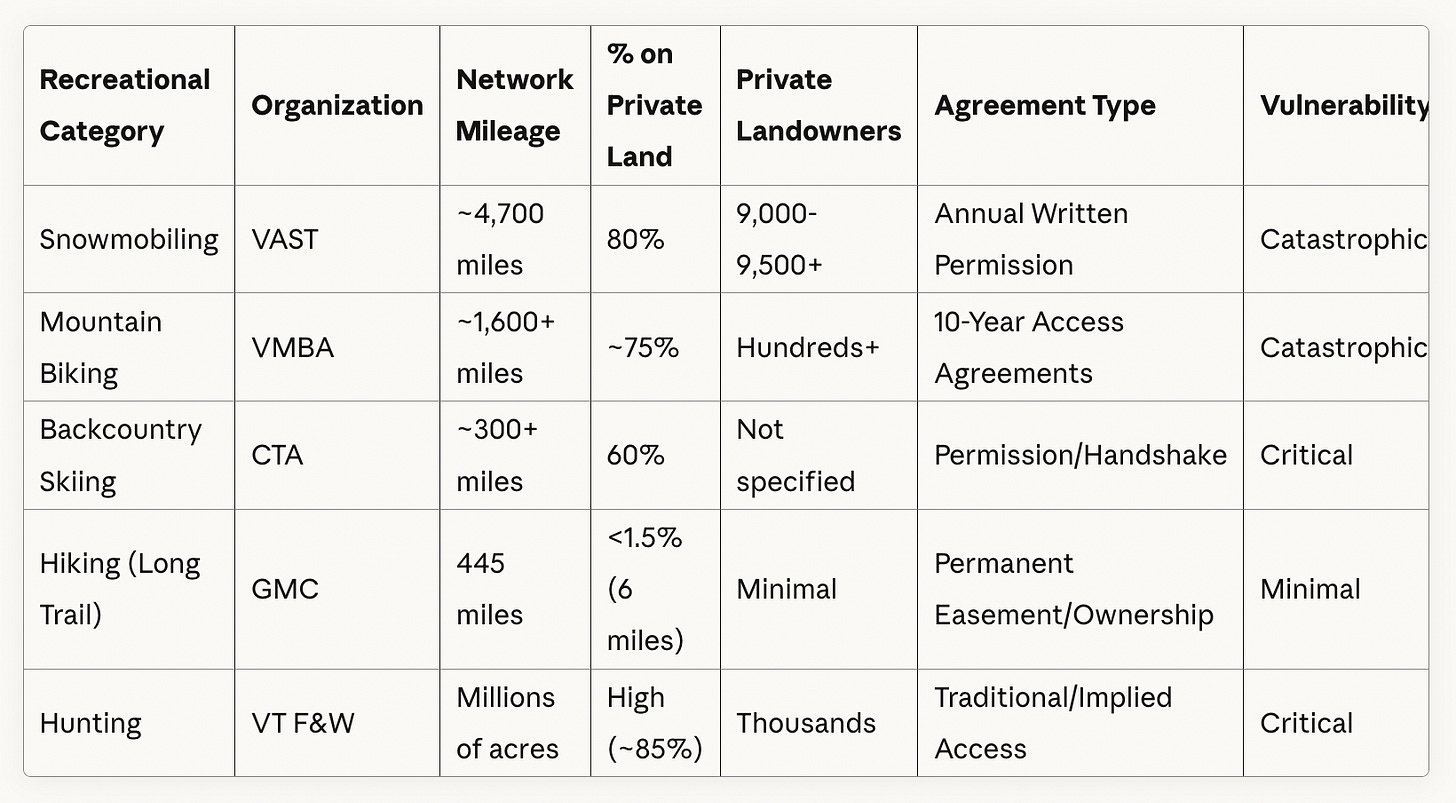

The numbers reveal the scale of this dependency. The Vermont Association of Snow Travelers (VAST) maintains approximately 4,700 miles of snowmobile trails, with 80% crossing private land owned by an estimated 9,000 to 9,500 individual property owners. The Vermont Mountain Bike Association (VMBA) oversees roughly 1,600 miles of mountain bike trails, with 75% on private property belonging to hundreds of landowners.

This arrangement exists because of simple geography: approximately 85% of Vermont is privately owned. Without private land access, a statewide recreational network is impossible.

A Vulnerability Spectrum

The degree of risk varies dramatically by activity:

The Green Mountain Club stands apart. After facing a crisis in 1986 when “handshake agreements were no longer enough” as land ownership changed, the organization launched a 30-year campaign to purchase land or permanent conservation easements. Today, only 6 miles of the 445-mile Long Trail remain unprotected, making it nearly immune to a mass revocation scenario.

The Compensation Question: Nothing

Here’s where property taxes enter the equation: Vermont landowners who allow public recreational access receive neither direct payment nor tax breaks for doing so.

In fact, accepting payment would be disastrous. Vermont’s landowner liability laws provide robust legal protection to property owners who allow free recreational use, shielding them from lawsuits unless they engage in “willful or wanton misconduct.” But this protection contains what analysts call a “tripwire”—if a landowner charges any fee, they instantly lose their liability shield and become vulnerable to negligence lawsuits.

Organizations like VAST and VMBA cannot pay landowners for access because doing so would expose those landowners to massive legal risk. The system depends entirely on unpaid generosity to keep the liability protections intact.

Similarly, Vermont’s “Current Use” tax reduction program lowers property taxes for landowners who manage their land for forestry or agriculture—not for providing recreational access. There is no provision in current law that reduces taxes specifically because a landowner allows public trail use.

The Dual Shield Keeping It Together

The permission economy functions only because of what researchers describe as a “dual shield” protecting landowners.

The first shield is statutory. Vermont’s general recreational use liability law treats recreational users as legal trespassers, dramatically limiting landowner liability. An even stronger protection exists for trails formally inducted into the “Vermont trails system”, where landowners face liability only if they “intentionally” inflict damage—a standard approaching absolute immunity.

The second shield is financial. VAST spends nearly $200,000 annually on trail liability insurance and contractually agrees to defend landowners or reimburse them for legal defense costs. VMBA provides similar protection, adding landowners as “additional insured” under its policies.

This dual shield makes participation rational for landowners. But if either part fails—whether through court decisions weakening liability protections, financial insolvency of trail organizations, or other factors—the incentive structure collapses.

The Breaking Point Scenario

Property taxes represent a potential catalyst. As Vermont grapples with property tax increases driven by education funding pressures and reappraisal crises, landowners face mounting annual costs. They receive no compensation for maintaining trails, no tax relief for providing access, and must renew permissions annually (in VAST’s case) while watching their tax bills climb.

The math becomes stark: thousands of dollars in annual property taxes, zero dollars in compensation, and the responsibility of allowing thousands of strangers onto their land each year.

Vermont’s outdoor recreation economy has effectively outsourced 4.8% of the state’s GDP to this unpaid arrangement.

Fractures in the System

The collapse scenario isn’t purely theoretical—it’s already happening in small-scale incidents.

In 2019-2020, three landowners at Kingdom Trails revoked permission due to frustration with overcrowding and user behavior. The loss of just 12 miles “effectively splits the Kingdom Trails system,” forcing trail closures and the cancellation of NEMBAfest 2020, a major economic event. Kingdom Trails, which generates $10.3 million in annual economic impact from 94,000 visitors, exists entirely on land owned by more than 100 private property owners.

In 2024, a VAST club reported that users forced open a gate on a trail the landowner had requested remain closed. The club warned the “rightfully upset” landowner “may CLOSE that trail permanently,” noting “that is a major trail for us with no way around it.”

Legal conflicts are also emerging. Landowners in Tunbridge sued their town over trail maintenance rights, resulting in years of expensive litigation that required legislative clarification.

The Economic Shockwave

A mass revocation would trigger immediate economic devastation because these trail networks derive value from connectivity, not total mileage. A single lost “connector” trail can render entire systems unusable.

The $220 million “snow activities” sector—the single largest contributor to Vermont’s outdoor recreation GDP—would face elimination. VAST alone claims over $500 million in annual economic impact.

Mountain biking destinations would vanish. World-renowned networks built on “critical community connectors” on private land would fragment into disconnected, unusable segments.

The cascading effect would cripple Vermont’s $4 billion tourism industry, which supports 31,053 jobs—9% of Vermont’s workforce. Tourism spending includes $1.4 billion for lodging, $830 million for food and beverages, and $658 million in retail.

The fiscal impact would be severe: the loss of $282.3 million in state and local tax revenue would equal a $1,048 tax increase for every household in Vermont.

For hunters, the impact would be cultural. The “open access” tradition would end, restricting access to 85% of Vermont’s land and disenfranchising the majority of the state’s 64,343 licensed hunters.

What Happens Next

Vermont faces what analysts describe as “two futures.”

The current path continues relying on the annual goodwill of 9,500+ individuals and the financial health of nonprofit organizations. This high-risk approach costs taxpayers relatively little in the short term but leaves 4.8% of the state’s GDP vulnerable to the triggers already manifesting in real-world incidents.

The alternative follows the Green Mountain Club’s model: systematically transitioning the most critical trail corridors from revocable permissions to permanent protection through conservation easements and land acquisition. This approach costs significantly more upfront but eliminates the systemic risk. As the GMC has noted, permanent protection is the only way to justify major capital investments needed to make trails resilient.

The question Vermont must answer: as property taxes rise and landowners face increasing financial pressure with zero compensation for providing recreational access, how long can a $2.1 billion economy built on unpaid generosity remain stable? And if policymakers believe the risk is real, what is the price of buying that risk off the books before it materializes into economic collapse?

The permission economy operates on trust, tradition, and the absence of better alternatives. Whether those forces can withstand the mounting pressures of Vermont’s property tax crisis may determine the future of the state’s outdoor identity and a substantial portion of its economic foundation.