Welch, Balint Target Rental Price Fixing — But That’s Not Vermont’s Problem

Vermont’s congressional delegation is pushing new federal legislation to ban rent-setting software, but experts say the state’s housing crisis has different roots.

In November 2025, Vermont’s U.S. Senator Peter Welch and Representative Becca Balint joined Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon in introducing the End Rent Fixing Act. The legislation would ban landlords from using computer algorithms that coordinate rental prices among competitors — a practice federal prosecutors say has illegally raised rents across the country.

But while the bill addresses a real problem in some parts of America, a detailed analysis of Vermont’s housing market reveals that algorithmic price-fixing is not what’s driving the state’s rental crisis. Instead, Vermont faces a fundamentally different challenge: there simply aren’t enough homes.

What the Legislation Does

The End Rent Fixing Act targets software platforms like RealPage’s “YieldStar” that collect private rental data from competing landlords and use it to recommend prices. According to the Department of Justice lawsuit filed in August 2024, these platforms allow landlords to share confidential information — like actual rents paid, lease renewal dates, and occupancy forecasts — that they would never share directly with competitors.

The software then generates daily pricing recommendations based on this pooled data, effectively coordinating rent increases across properties that should be competing with each other. Federal prosecutors argue this creates an illegal “hub-and-spoke” conspiracy, where the software company serves as the hub connecting competing landlords.

A White House Council of Economic Advisors report estimated that these practices transferred $3.8 billion from renters to landlords in 2023. In November 2025, Greystar Management Services — the nation’s largest landlord — agreed to pay $7 million to settle claims that it used such software to artificially inflate rents.

Why This Isn’t Vermont’s Problem

The algorithmic rent-fixing scheme depends on a specific market structure: large corporate landlords controlling most of the rental supply in a city or region. That’s the reality in places like Atlanta, Dallas, and Phoenix, where national real estate investment trusts and private equity firms own sprawling apartment complexes.

Vermont’s rental market looks nothing like that.

According to market analysis, approximately 98% of single-family rental homes in Vermont are not corporate-owned. The typical Vermont landlord is a local family or individual who owns a duplex, a converted house, or a small cluster of units. These “mom-and-pop” landlords set rents based on what they see advertised on Craigslist or Facebook Marketplace — not through expensive enterprise software.

Even in Burlington, the state’s largest city, the rental market is fragmented among local companies, family-run operations, and the nonprofit Champlain Housing Trust, which manages over 2,300 affordable units priced below market rates. While some larger Burlington management companies use property management software from companies like Yardi or AppFolio, they aren’t pooling data in the same system — which means they can’t effectively coordinate prices.

The Real Problem: Not Enough Housing

Vermont’s housing crisis is driven by severe scarcity. The state’s rental vacancy rate hovers around 3% statewide, and in Chittenden County, it’s just 1%. In a healthy rental market, vacancy rates are typically around 5%, giving renters options and forcing landlords to compete for tenants.

At a 1% vacancy rate, the opposite happens: dozens of applicants compete for every available apartment. Landlords don’t need a computer algorithm to tell them they can raise the rent — the desperation of applicants signals this immediately.

The Vermont Housing Finance Agency calculates that the state needs to add between 24,000 and 36,000 new housing units by 2029 to restore market balance and accommodate growth. That shortage accumulated over a “lost decade” following the 2008 recession, when housing construction in Vermont collapsed and never fully recovered.

The Tourism Factor: Airbnb and Second Homes

Another major factor squeezing Vermont’s housing supply is the conversion of homes into short-term rentals and vacation properties. According to the 2025 Vermont Housing Needs Assessment, approximately 15% of the state’s total housing stock — about 51,474 homes — is classified as seasonal or vacation homes. In some counties like Essex and Grand Isle, nearly 40% of homes are seasonal.

There are currently over 11,000 whole-unit short-term rentals operating in Vermont through platforms like Airbnb and Vrbo. The average monthly revenue for these rentals reached $4,100 in 2023 — more than double the typical $1,900 fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment. This creates a powerful financial incentive for property owners to convert long-term rentals into vacation stays.

While these short-term rentals generate over $1 billion in tourism revenue annually for Vermont, they effectively remove housing from the market that working Vermonters need.

The Homelessness Crisis

The human cost of Vermont’s housing shortage is stark. The 2025 State of Homelessness in Vermont Report documented that the number of unhoused Vermonters has roughly tripled since 2019, with 3,386 individuals experiencing homelessness on a single night in 2025, including over 633 children.

However, advocates and service providers identify causes distinct from algorithmic pricing. The surge in homelessness is driven primarily by cuts to the General Assistance Emergency Housing Program (the state’s motel voucher system), the loss of pandemic-era protections, and a simple lack of shelter beds. Household shelter capacity actually decreased from 655 to 602 placements in mid-2025 due to seasonal shelter closures.

For families relying on emergency assistance, the fact that a luxury apartment in Burlington might use pricing software is irrelevant — they’re priced out of the market entirely.

Two Different Housing Crises

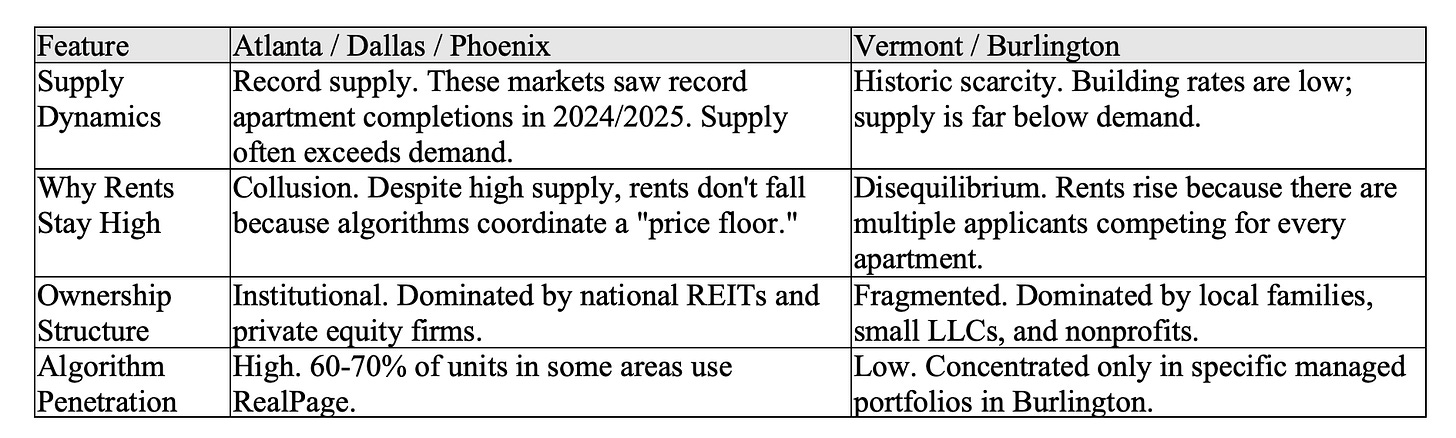

The contrast between Vermont’s situation and the markets targeted by federal prosecutors is striking:

What Vermont’s Congressional Delegation Is Working On

Despite Vermont’s different circumstances, Senator Welch and Representative Balint are co-sponsoring the End Rent Fixing Act as part of a broader federal response to housing affordability nationwide.

The legislation would make it a “per se” violation of federal antitrust law for landlords to use algorithms that coordinate pricing using competitors’ confidential data. This designation means the practice would be automatically illegal, without requiring prosecutors to prove specific harm in each case — similar to how price-fixing agreements are treated.

The bill would also invalidate pre-dispute arbitration agreements in rental contracts, making it easier for tenants to file class-action lawsuits against landlords who use such software.

While these provisions primarily address problems in large metropolitan areas with concentrated corporate ownership, Senator Welch has emphasized that the legislation serves as a preventive measure. As he noted in the press release, it would ensure that if Vermont’s rental market eventually attracts more institutional investors, the algorithmic pricing mechanism will already be banned.

What Happens Next

For the federal legislation:

The End Rent Fixing Act has been introduced in both the Senate (by Senators Wyden and Welch) and the House (by Representatives Balint and Jesús “Chuy” García of Illinois). The bill will be referred to the Judiciary Committees in both chambers, where it will need hearings and committee approval before advancing to floor votes. Given the bipartisan concern about housing affordability, the legislation could gain traction, though its path through Congress remains uncertain.

Meanwhile, the Department of Justice’s lawsuit against RealPage continues in federal court, and the recent Greystar settlement may encourage other large property management companies to voluntarily stop using algorithmic pricing tools to avoid legal liability.

For Vermont:

The state’s housing crisis requires different solutions focused on increasing supply and addressing the conversion of housing to short-term rentals and vacation homes.

Act 181, passed by the Vermont Legislature in 2024, reformed the state’s Act 250 land-use law to make it easier to build housing in designated growth centers (downtowns and village centers). The full implementation of these reforms continues through 2027, with interim housing exemptions currently in place. However, experts note that the supply response will take time — new housing construction typically takes 18-24 months from permitting to completion.

State lawmakers continue to debate regulations on short-term rentals, weighing the economic benefits of tourism against the need to preserve housing for year-round residents. Some Vermont towns have enacted local restrictions, but statewide action remains politically contentious.

The Vermont Housing Finance Agency continues to work with the legislature on funding mechanisms to close the 24,000 to 36,000 unit gap identified in the 2025 Housing Needs Assessment. This includes exploring increased funding for affordable housing development, infrastructure investments to support new construction, and programs to incentivize the conversion of vacant or seasonal properties to year-round housing.

For advocates addressing homelessness, the immediate priority remains restoring funding and capacity to the General Assistance Emergency Housing Program and increasing permanent supportive housing units.

The bottom line: While banning algorithmic price-fixing may help renters in Atlanta or Dallas, solving Vermont’s housing crisis will require building thousands of new homes, addressing the conversion of housing to vacation rentals, and rebuilding the social safety net for the state’s most vulnerable residents.