Want to Buy a Vermont Lawmaker a Fancy Trip and Not Tell Anyone? It's Simple, Just Don't Register as a Lobbyist.

Without a disclosure law that covers such gifts, the public is left in the dark, unable to connect a lavish trip to a lawmaker’s subsequent legislative actions.

As noted in a recent article in Seven Day, if a registered lobbyist in Vermont gives a state senator a sweatshirt worth $70, it must be publicly reported for all to see. If a foreign government gives five state representatives an all-expenses-paid trip worth over $32,000, it doesn’t have to be reported at all.

This isn’t a hypothetical scenario. It’s the reality of Vermont’s ethics laws, a system with a loophole so vast that it renders most discussions of transparency meaningless. A recent, controversial trip to Israel by five Vermont lawmakers has pulled back the curtain on this fundamental flaw: the laws are designed to track small gifts from known players inside the State House, while leaving the door wide open for powerful, wealthy, and often foreign interests to give lavish gifts with no public disclosure required.

The issue isn’t a technicality or a minor exemption for travel. It’s a one-sided system that places the burden of reporting gifts exclusively on registered lobbyists. If you’re not on that specific list, you can give a lawmaker almost anything you want, and no one has to tell the public. This article breaks down how this system works, what’s missing from the story, and what a path to real accountability could look like for Vermonters.

A Case Study in Influence: The “50 States, One Israel” Trip

In September 2025, Vermonters learned—not from an official disclosure, but from a social media post by the Israeli government—that five of their state representatives were in Israel on a trip paid for by the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Representatives Sarah “Sarita” Austin, Matt Birong, Gina Galfetti, Will Greer, and James Gregoire attended the “50 States, One Israel” conference, with all expenses covered. According to reports, the value of this gift was estimated at $6,500 per person.

While the trip was defended by some attendees as an educational opportunity, a deeper look reveals it was a targeted influence campaign with specific legislative goals.

A Direct Lobbying Effort: This wasn’t just a cultural tour. According to reports, a central theme of the conference was a direct call from Israeli officials for the visiting American legislators to pass state-level laws barring boycotts, divestments, or sanctions (BDS) against Israel. The trip’s purpose was to directly influence state-level legislation across the United States.

The Connection to a Vermont Bill: This lobbying effort has a direct and tangible link to pending legislation in Montpelier. Research shows that four of the five Vermont attendees—Reps. Birong, Greer, Austin, and Galfetti—are co-sponsors of a Vermont House bill, H.310. According to reporting from The Rake Vermont, this bill seeks to amend the state’s definition of harassment in schools with language that aligns with the policy goals promoted at the conference. The gift of a $6,500 trip is not an abstract gesture; it is directly connected to a policy outcome sought by the gift-giver and advanced by the recipients.

The Geopolitical Context: The trip occurred at a highly charged moment. Just one day before, an independent United Nations commission released a report concluding that Israel was committing genocide in Gaza, an accusation echoed by all three members of Vermont’s own federal delegation. The decision to accept a government-sponsored trip at the very moment that government was facing such serious accusations from international bodies and the state’s own representatives is the core of the public controversy.

Without a disclosure law that covers such gifts, the public is left in the dark, unable to connect a lavish trip to a lawmaker’s subsequent legislative actions.

The Real Loophole: It’s Not What You Give, It’s Who You Are

So, why is a $70 sweatshirt reported while a $32,500 trip for five isn’t? The answer is simple and reveals the central flaw in Vermont’s ethics framework.

The reason the sweatshirts were disclosed is that the giver, the Vermont State Colleges, is a registered lobbyist employer. Under Vermont law, registered lobbyists and their employers must file reports itemizing every gift they give to a legislator with a value greater than $15. The legal burden is entirely on the giver.

The Israeli government, however, is not a registered lobbyist in Vermont. Because the giver falls outside this narrow legal category, it has no obligation to report anything. Crucially, Vermont law places no corresponding duty on the legislative recipient to publicly disclose the gift.

This is the entire loophole. It has nothing to do with whether travel is considered a “gift”—the law explicitly states that it is. The problem is that the disclosure requirement is only triggered by a small, specific group of registered, in-state players. This creates a deeply paradoxical system:

A $35 lunch from a Vermont-based lobbyist must be publicly reported.

A $6,500 international trip from a foreign government, a national corporation, or a wealthy individual requires no disclosure at all.

This framework inverts the basic principle of good governance. It applies the highest scrutiny to the smallest gifts from the most visible actors, while providing zero transparency for the largest gifts from the most powerful and potentially influential outside sources.

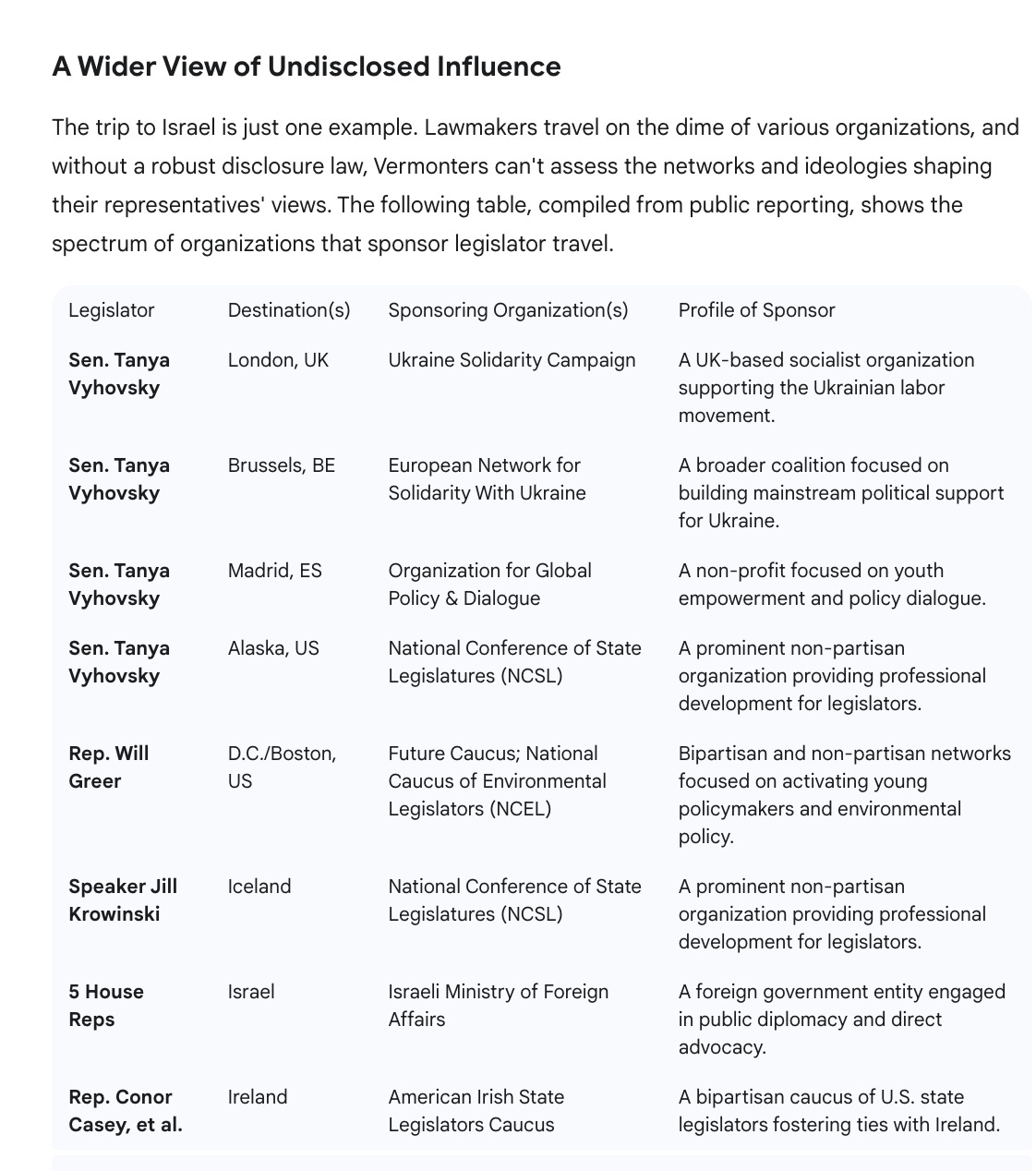

What this table reveals is a pattern. Legislators often accept travel from groups that align with their existing political ideologies, policy interests, or personal heritage. Following a trip sponsored by the American Irish State Legislators Caucus, for example, a new Vermont-Ireland Trade Commission was created. These trips aren’t just vacations; they are a means of deepening ideological commitments and building specialized networks that can translate directly into policy back in Vermont.

The Watchdog With a Delayed Bark

One might assume the Vermont State Ethics Commission would police this. However, as its own executive director has stated, the state’s ethics policy “lacks key measures to provide transparency or give it teeth.”

Currently, the Commission is little more than a referral service. According to its mandate, it can receive complaints, but it cannot investigate them. Instead, it passes them on to other bodies, like the House or Senate Ethics Panels.

The legislature recently took a step to change this. In June 2024, it passed Act 171, a law that for the first time grants the Commission the power to conduct its own investigations into alleged ethics violations. However, there’s a catch: the new powers don’t become effective until September 1, 2025.

So, while the legislature has moved to empower the state’s watchdog, it chose a protracted timeline, leaving Vermont’s accountability gap wide open for another year.

How to Fix This: A Clear Path to Transparency

Closing this loophole and creating a system of real accountability doesn’t require reinventing the wheel. It requires adopting common-sense reforms that are standard practice in other states and at the federal level.

Mandate Recipient-Side Reporting. The core problem is that the reporting burden is only on the giver. The solution is to put it on the recipient as well. A new law should require every legislator to publicly report any gift of travel—including transportation, lodging, and meals—above a reasonable threshold (e.g., $250). This single change would close the loophole for gifts from foreign governments, corporations, and any other non-lobbyist entity.

Create a Centralized Public Database. Disclosure is only useful if the information is easy to find. Vermont should create a single, searchable online database where all legislator gift and travel reports are filed. This would allow any citizen or journalist to easily track who is giving what to whom.

Fully Empower and Fund the Ethics Commission. The legislature should stick to the September 2025 date for the Commission’s new investigative powers, and critically, provide it with the budget and staff to do its job effectively. A law with no enforcement is just a suggestion.

Learn from Other States. Vermont can look to states like Massachusetts and New York, which have developed detailed regulations for gifted travel, or Wisconsin, which has a near-total ban on gifts from lobbyists. Strong, proven models for reform already exist.

The current system fails Vermonters. It allows powerful outside interests to secretly cultivate influence with lawmakers through lavish gifts, undermining public trust and the integrity of the democratic process. By adopting these straightforward reforms, Vermont can close the door to undisclosed influence and build a more transparent and accountable government.