Vermont’s WWII Aircraft Spotters: Watching the Skies at Home

Springfield and Windsor, Vermont were considered key targets.

Vermont’s WWII Aircraft Spotters: Watching the Skies at Home

This story is inspired by the memory of our grandparents, who were volunteer spotters in Northfield during World War II. Too old to serve overseas, they and countless others across Vermont took up posts on hilltops, in bell towers, and at makeshift shacks to keep watch for enemy aircraft that, at the time, many feared might one day appear over New England skies.

The Aircraft Warning Service Comes to Vermont

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the Nazi bombing raids on Britain, U.S. leaders worried that America’s own industrial centers might be targeted. Vermont, though rural, was not dismissed as irrelevant. Factories in Springfield and Windsor were essential to the war effort, producing machine tools so critical to aircraft and weapons manufacturing that military planners considered them vulnerable targets.

In 1941 the U.S. Army established the Aircraft Warning Service, creating a civilian Ground Observer Corps of plane-spotters across the nation. Their mission was simple: report every aircraft that passed overhead, day or night. Each report was phoned in to a regional “Filter Center” that could quickly verify whether the planes were friendly or suspicious.

Vermont’s Watch Posts

Observation posts were scattered across Vermont. Burlington had two: one on the Old Mill bell tower at the University of Vermont, and another atop the Ethan Allen Tower in the city’s namesake park. Other posts dotted smaller towns—Shelburne Point, Richmond, Jonesville, Williston, and Northfield among them.

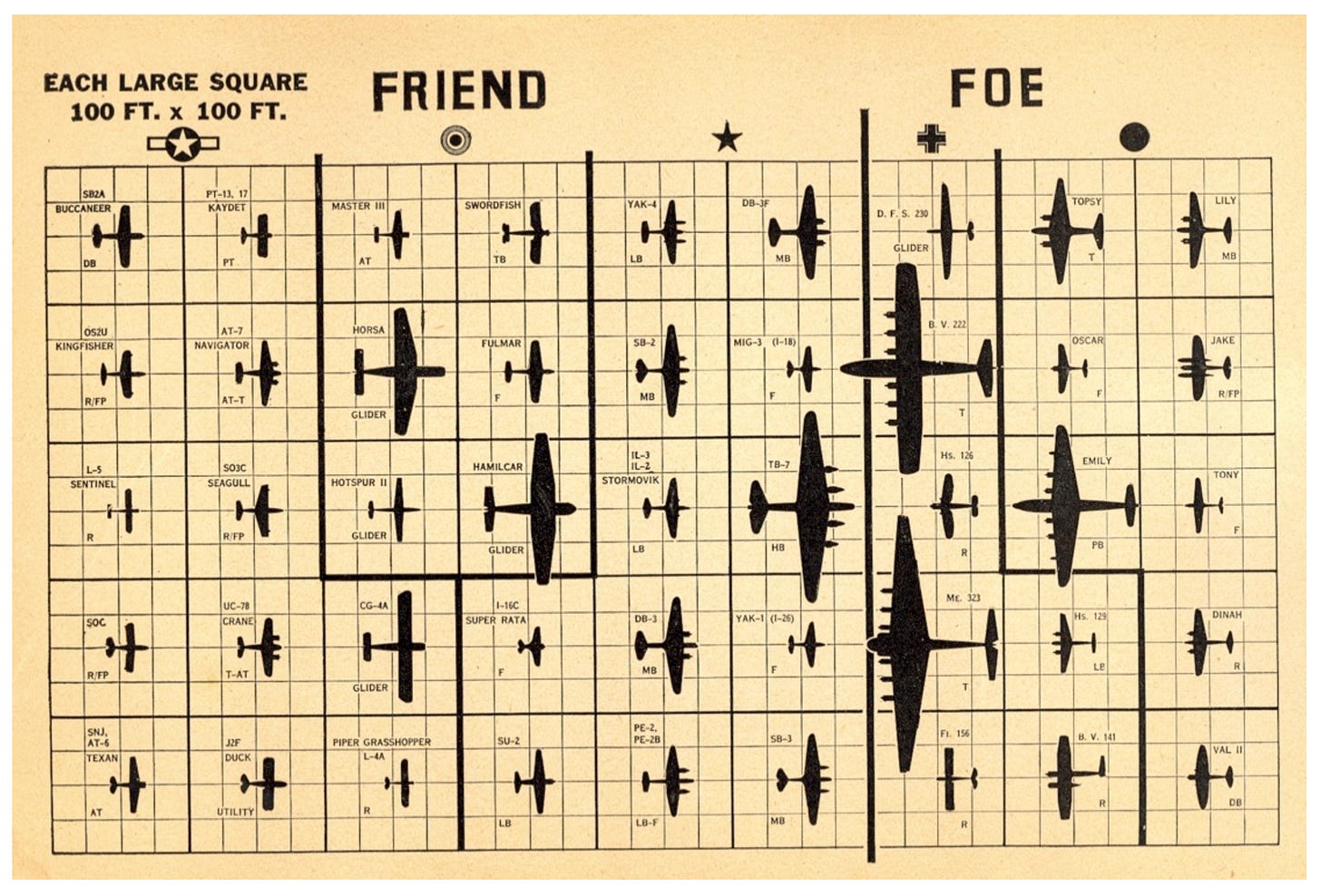

Volunteers worked around the clock, often in two-person shifts. Women frequently covered the daylight hours, while men took overnight turns. Spotters were issued silhouette charts, flashcards, and manuals to help them tell the difference between American bombers, British Spitfires, and the planes of the Axis powers. Many recall the anxiety of straining eyes to identify distant specks in the sky, knowing that a mistake could be costly.

A Community Effort

The posts themselves became community hubs. In Williston, townspeople outfitted an old gas-station shack with insulation and a woodstove so volunteers could endure Vermont’s winters. Some posts screened training films, hosted dances, and handed out collectible pins to recognize the service of spotters.

Most days were quiet, filled with routine calls about passing transport planes or training flights. Still, vigilance occasionally made a difference: observers in Shelburne spotted a barn fire in time to save livestock, while another crew in Williston noticed a horse caught in a fence and alerted the farmer.

Key Targets of Concern

Although no Axis bombers ever reached Vermont, military planners worried about the possibility. Several sites in New England were considered potential targets:

Springfield, Vermont – Known as the “Precision Valley,” Springfield’s machine tool companies—Jones & Lamson, Fellows Gear Shaper, and Bryant Grinder—were world leaders in precision manufacturing. Their tools were vital to building aircraft engines, tanks, and guns. Protecting these factories was a priority, and spotter posts were placed nearby as an added precaution.

Windsor, Vermont – Factories here produced gun-making machinery and industrial tools that fed directly into the war effort.

Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (Kittery, Maine) – A critical submarine construction and repair facility, Portsmouth was seen as a prime target for German U-boats or bombers.

Boston Harbor & Shipyards – Home to major naval facilities, dry docks, and warehouses supplying the Atlantic Fleet.

Maine’s Oil Refineries and Ports – The East Coast shipping lanes were already under attack by German U-boats in 1942, and Maine’s ports, including Portland, were feared to be within range of enemy submarines or surface raiders.

The Fear Wasn’t Just Imagined

The fear of attack on Vermont and its neighbors was not simply paranoia. In early 1942, German U-boats prowled so close to the New England shoreline that residents in Cape Cod and Maine reported watching merchant ships explode within sight of the coast. Dozens of tankers and freighters were sunk off the Atlantic seaboard during what became known as the “Second Happy Time” of the U-boat campaign. On the West Coast, a Japanese submarine shelled an oil refinery near Santa Barbara, California, proving that enemy forces could and would strike the U.S. mainland. German spies were even landed by submarine on Long Island and in Maine in failed sabotage missions. With these fresh examples, the idea of Springfield’s factories—or even Boston’s shipyards—being bombed no longer felt far-fetched. For Vermonters standing night watch in their observation posts, the war was not a distant overseas event but a potential reality overhead.

A Real False Alarm

False alarms were surprisingly common—often due not to enemy craft, but to misidentified friendly planes or even weather balloons. For example, in 1943 a spotter post on the East Coast once scrambled military interceptors after reporting what they believed to be a formation of enemy aircraft; it turned out to be a captured German plane, with U.S. markings, being flown back for examination—yet the recognition training of the observers had worked exactly as planned, demonstrating both the program’s efficacy and the blurry line between vigilance and alarm facebook.com+3en.wikipedia.org+3en.wikipedia.org+3. Though not from Vermont specifically, this true incident mirrors what volunteers across the network experienced—(night watches ending in phone calls to filter centers only to discover the “threat” was a benign aircraft in abnormal circumstances). It underscores the tension and intensity of duty Vermont volunteers carried with quiet courage.

The Threat That Never Came

In the end, no German or Japanese aircraft ever darkened Vermont’s skies. But the threat was real enough at the time to mobilize thousands of volunteers across the state. By late 1943 the fear of air raids had eased, and the Army began winding down the program. In May 1944 the Aircraft Warning Service was officially shut down.

For Vermont, the plane-spotter program was less about spotting enemies than about uniting communities in a shared sense of duty. From Springfield’s critical factories to Northfield’s quiet hills, ordinary citizens stood watch, proving that even those who could not carry a rifle could still defend their state.

Attributions:

Information for this story draws on research and historical records from the Vermont Historical Society, the Williston Historical Society, the Woodstock History Center, and accounts preserved in local archives. National context comes from U.S. Army histories of the Aircraft Warning Service and the Ground Observer Corps. Additional details on strategic targets come from Vermont industry histories, New England wartime planning documents, and historical studies of U-boat activity off the East Coast. The false-alarm anecdote is based on documented incidents from the Aircraft Warning Service where captured or Allied-marked planes were misidentified as threats and reported accordingly