Vermont's Expanded Bottle Bill is Back with a New Plan - Will it Float This Time?

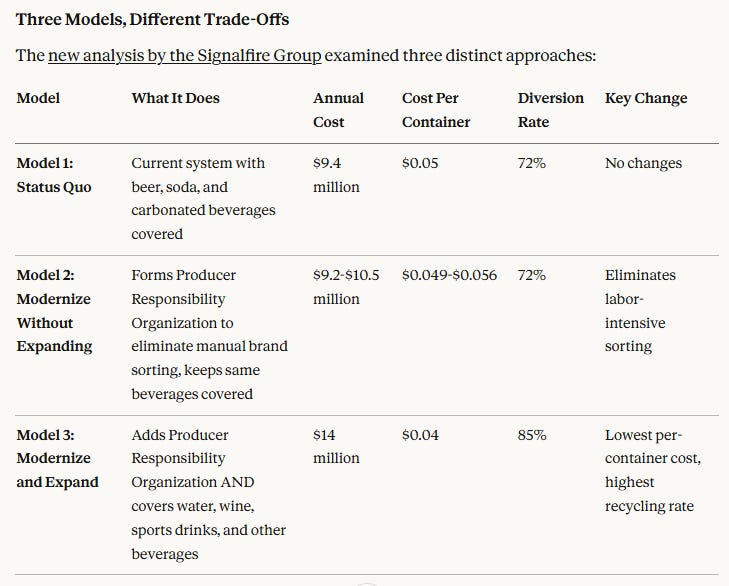

Study shows expansion could cut costs per container while boosting recycling, while the overall cost of the program would increase by $4.6 million.

Vermont lawmakers are making a fresh push to overhaul the state’s 50-year-old bottle redemption system, armed this time with detailed financial modeling that challenges key arguments from opponents of expansion.

The effort comes nearly two years after Governor Phil Scott vetoed similar legislation and the Senate fell three votes short of overriding him in January 2024. Now, a comprehensive study commissioned by the Department of Environmental Conservation and presented to legislators this month offers new evidence about what different approaches would cost and accomplish.

What the Current System Does

Vermont’s bottle deposit law, enacted in 1972, currently covers beer, malt beverages, carbonated soft drinks, mineral waters, and mixed wine drinks. Consumers pay a 5-cent deposit on most containers and 15 cents on liquor bottles over 50 milliliters, which they can reclaim by returning empties to one of approximately 123 redemption locations statewide.

Everything else—water bottles, sports drinks, iced tea, wine, and juice containers—goes into curbside recycling bins or gets thrown away. This split system currently achieves a 72% redemption rate for covered beverages.

The Labor Problem That Sparked the Veto

When Governor Scott vetoed expansion legislation in June 2023, he called the bottle bill a “labor-intensive 1970s-era” system and questioned its efficiency. His concerns centered on the manual work required at redemption centers, where staff must sort returned containers by brand so each distributor only pays for its own bottles.

The governor also raised equity concerns, asking what apartment dwellers without vehicles were “supposed to do with all the bottles” if the nearest redemption center was miles away. He argued that expanding the deposit system would pull valuable aluminum and plastic from curbside recycling, destabilizing material recovery facilities.

The Expansion Math

While expanding the bottle bill would increase the system’s total annual cost to $14 million—nearly 50% more than today—the per-container cost would drop to 4 cents, the lowest of any scenario. This efficiency gain comes from spreading fixed costs across a much larger volume of containers and capturing cleaner materials that command higher resale prices.

The environmental benefits scale up accordingly. The study projects expansion would boost the overall diversion rate to 85% and avoid an additional 4,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually. Roadside litter would drop by 22%.

The Impact on Curbside Recycling

The study found that removing high-value aluminum and plastic from curbside bins would increase costs for material recovery facilities by about 2%—from $37.95 million to $38.85 million annually. Casella Waste Systems, the dominant waste hauler in the region, has historically opposed expansion on these grounds, arguing the increased costs would ultimately fall on municipalities and residents.

What’s in the Current Bill

House Bill 119, introduced in January 2025, would implement the expanded model. The deposit would increase from 5 cents to 10 cents to account for inflation and drive participation rates above 85%, based on results from Michigan and Oregon.

The bill explicitly adds water, wine, hard cider, and “hard kombucha” to the covered beverages list, and aligns the definition of “soft drink” with existing tax code to capture non-carbonated varieties. Redemption centers would receive 3.5 to 4 cents per container as a handling fee.

Who Supports and Opposes the Changes

Environmental groups including VPIRG and the Container Recycling Institute see the study as validation that comprehensive deposit systems produce cleaner recyclables than single-stream curbside collection. Bottles returned for deposit are clean enough to become new food-grade containers, while curbside materials often get contaminated and must be downcycled into carpet or other lower-value products.

Retailers have traditionally resisted bottle bills due to space and sanitation concerns, though the Producer Responsibility Organization model shifts much of the logistics burden away from individual stores. The waste management industry’s concerns about lost curbside revenue remain a key political obstacle, though the study quantifies that impact as relatively modest compared to the environmental gains.

What Happens Next

The study was presented to the House Environment Committee on January 8, giving lawmakers detailed financial modeling as they consider H.119. The committee will hold additional hearings before deciding whether to advance the bill.

If the legislation gains traction, proponents will need to either win the governor’s support or secure the votes needed to override another potential veto. That likely means addressing concerns about convenience in rural areas and finding compromise language on the curbside recycling impact. A realistic timeline would see legislation pass in 2026, the Producer Responsibility Organization formed over the following year, and new systems operational by 2027 or 2028.

The fundamental question facing lawmakers is whether the efficiency gains and environmental benefits of a comprehensive system justify the higher total cost and the disruption to existing recycling arrangements. The new data offers specifics for that debate, but the political calculation remains unchanged: three Senate votes stand between the status quo and transformation.