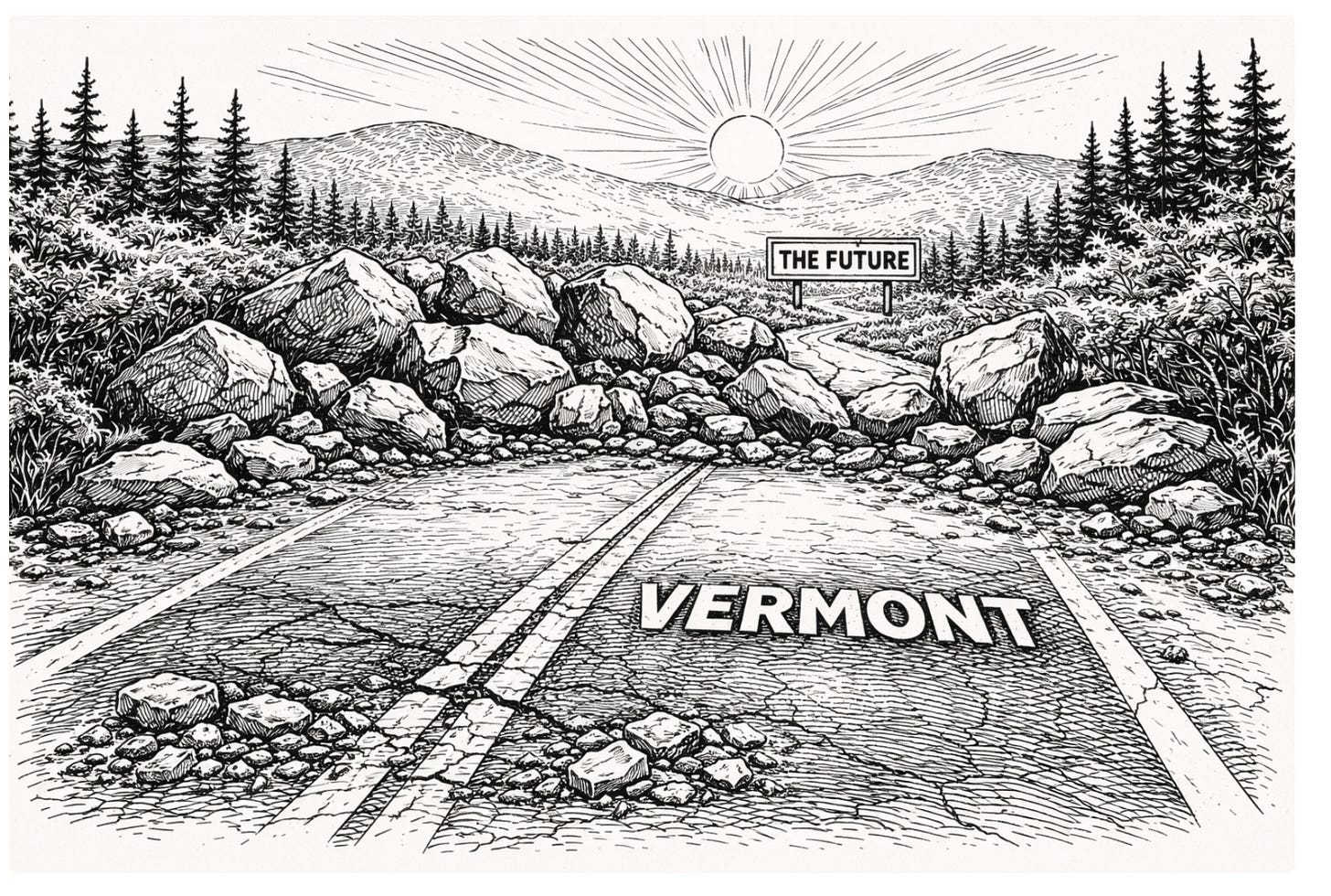

Vermont Trapped in "Institutional Sclerosis": Lessons from States That Forced Radical Reform

For Vermont, the "different scenarios" converge on a single truth: the system does not change until the cost of stability exceeds the cost of reform.

Across the United States, states occasionally reach a breaking point where familiar patterns—rising costs, tax increases, regulatory gridlock—seem locked in place with no apparent way forward. Political scientists call this “institutional sclerosis,” and Vermont isn’t alone in facing it.

A comprehensive analysis of state governance over the past three decades reveals that when political systems become entrenched, change rarely happens gradually. Instead, reform typically arrives through dramatic ruptures—moments when the cost of maintaining the status quo finally exceeds the cost of radical change.

By examining how other states have broken similar deadlocks, Vermont residents can better understand the mechanisms that force political and fiscal reset buttons, from Michigan’s education funding crisis to Connecticut’s business exodus and Montana’s housing emergency.

Four Pathways to Breaking Deadlock

Researchers have identified four primary scenarios that break political stalemates: the “calculated crisis” where legislatures deliberately blow up existing systems, “fiscal guardrails” imposed by external market forces, “strange bedfellows” coalitions that unite unlikely allies, and judicial mandates that force legislative action.

Each pathway differs in who initiates change, how deadlocks break, and what outcomes emerge. Most importantly, history shows these ruptures happen not through incremental reform, but through decisive moments when maintaining existing structures becomes politically or economically impossible.

The Calculated Crisis: Michigan’s Nuclear Option

In 1993, Michigan faced a situation familiar to many states: skyrocketing property taxes funding education, deep inequity between wealthy and poor districts, and twenty years of failed reform attempts. The legislature had tried twelve ballot proposals and countless incremental fixes, but the system remained stuck.

The Radical Maneuver

During a July 1993 debate on modest property tax cuts, Democratic State Senator Debbie Stabenow proposed an amendment to repeal all local property taxes for school operations—roughly $6 billion in revenue—without any replacement plan. Rather than voting down what seemed like a chaotic measure, Republican Governor John Engler urged his party to support it.

The measure passed the Senate 33-4 and the House 69-35. Overnight, Michigan eliminated the primary funding source for public schools, effective the following school year. Schools would close in twelve months unless a completely new tax system was built from scratch.

Rebuilding from Zero

This self-imposed crisis shattered the power of interest groups that had blocked reform. Teachers’ unions, local school boards, and property tax advocates could no longer defend the status quo because the status quo had been legally abolished.

The legislature presented voters with a binary choice in March 1994. Voters chose Proposal A by a 69% margin, fundamentally restructuring education funding. The state replaced local property taxes with sales tax increases and a capped statewide property tax, cutting property tax burdens by $63 billion over ten years.

The Decoupling Effect

The most profound change was severing the link between local property wealth and school budgets. Before Proposal A, a district’s funding tied directly to property values and residents’ willingness to vote for tax increases. After reform, the state assumed revenue responsibility, setting per-pupil funding amounts.

Proposal A also placed hard caps on taxable value, preventing assessment increases beyond inflation or 5%, whichever was less. This protected homeowners from being priced out during housing bubbles.

By removing the easy property tax lever, Michigan forced cost control conversations that had been avoided for decades. Sales tax revenues don’t grow as aggressively as property assessments, naturally imposing spending discipline.

External Discipline: Connecticut’s Bond Market Intervention

While Michigan’s rupture came from within, Connecticut’s reform was forced by external market pressure. Following the Great Recession, Connecticut entered what lawmakers called a “permanent fiscal crisis”.

The Breaking Point

Connecticut relied heavily on volatile revenue from Fairfield County hedge funds. When markets rose, the legislature spent windfalls on recurring obligations. When markets fell, deficits exploded. To close gaps, the state passed two massive tax increases—$2.5 billion in 2011 and $1.3 billion in 2015.

The cycle triggered visible corporate departures. In 2016-2017, General Electric and Aetna announced headquarters relocations to Boston and New York. GE explicitly cited Connecticut’s tax policies and fiscal disorder. Credit rating downgrades followed, raising borrowing costs. The 2017 budget process collapsed, leaving the state without a budget for four months.

Binding Future Legislatures

The crisis empowered moderate Democrats and Republicans to force structural change. They realized that promises to spend less were insufficient—future legislatures would break those promises. They needed mechanisms to bind future majorities’ hands.

The result was the 2017 Bipartisan Budget establishing strict “Fiscal Guardrails”. Crucially, the legislature wrote these guardrails into bond covenants—contracts with investors—for five to ten years, creating a “Bond Lock.”

Revenue from volatile sources exceeding $3.15 billion must divert to reserves. The legislature cannot budget to spend 100% of projected revenue. And repealing these caps would trigger technical default on state bonds.

Dramatic Results

By forcing the state to save rather than spend windfalls, Connecticut built its Rainy Day Fund to its statutory maximum. Between 2018 and 2024, the state paid down billions in pension debt and received multiple credit upgrades. The endless cycle of tax hikes halted, and the state enacted tax cuts.

The Bond Lock proved essential. When progressive lawmakers sought to bypass spending caps, they were legally blocked by bond covenants. The mechanism effectively outsourced fiscal discipline to the bond market.

The Massachusetts Counterweight

Another variation on external discipline occurred in Massachusetts in the 1990s. Known derisively as “Taxachusetts”, the state featured high taxes, economic stagnation, and an overwhelmingly Democratic legislature.

Divided Government as Friction

Reaching a breaking point, voters elected Republican Governor William Weld in 1990. Unlike an “immovable majority” scenario, Massachusetts’s legislature was forced to negotiate with a governor wielding veto power.

Weld’s administration focused on privatization of state services, contracting out work to break public sector union monopolies. He cut taxes 21 times, targeting capital gains and income taxes to spur investment.

Massachusetts shed the “Taxachusetts” label. Unemployment dropped and economic boom followed. The presence of an opposing-party executive willing to veto legislation forced legislative moderation.

Strange Bedfellows: Breaking Regulatory Strangleholds

Breaking decades-old environmental or zoning regimes requires fundamental political realignment. The traditional left-versus-right divide—where progressives protect regulation and conservatives protect property owners—often calcifies the status quo. Change requires new coalitions uniting pro-market conservatives with social-equity progressives.

The Montana Miracle

Post-2020, Montana experienced a massive remote worker influx, causing median home prices to rise 90% between 2018 and 2023. Local zoning boards and regulations stifled new supply. The “immovable” forces were local governments defending “home rule” and existing homeowners protecting property values.

The housing crisis became an economic crisis—businesses couldn’t hire because workers couldn’t find housing. Governor Greg Gianforte issued an executive order creating a Housing Task Force with a mandate to produce actionable legislation.

State Preemption

The task force produced legislation—dubbed the “Montana Miracle”—that the 2023 legislature passed, stripping local governments of power to block certain development.

SB 323 required cities over 5,000 population to allow duplexes on any single-family lot. SB 245 forced municipalities to allow multifamily housing in commercial zones. SB 382 completely overhauled land use planning, requiring localities to plan for growth rather than restrict it.

The Coalition

The reforms passed because they shattered traditional alliances. Conservatives supported them as property rights restoration—arguing zoning tells property owners what they can’t do with their land. Progressives supported them as social justice measures—arguing exclusionary zoning prevents affordable housing and segregates communities.

The “immovable” coalition of local officials and neighbors was isolated by this pincer movement. The League of Cities and Towns opposed the measures, but was outvoted by the bipartisan state coalition.

Oregon’s Blue State Version

Oregon became the first state to effectively ban single-family zoning in cities. House Bill 2001 in 2019 required cities to allow “middle housing”—duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes—in areas previously reserved for single-family homes.

Proponents successfully reframed the debate. Instead of “Development versus Environment,” the frame became “Density versus Sprawl.” By arguing that density reduces carbon footprints and prevents sprawl into forests, “Smart Growth” environmentalists split from “Preservationist” environmentalists.

The bill received support from over 25 organizations, including AARP and racial justice groups who argued zoning was a segregation tool.

California’s CEQA Reform

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) was considered “untouchable” for decades, used by labor unions to leverage wages and neighbors to block housing. Facing catastrophic housing shortages, Governor Newsom and the legislature passed SB 131 and AB 130, creating significant CEQA exemptions for infill housing.

The trigger was realization that environmental law was harming the environment by forcing development into wildfire zones rather than urban centers. The legislature declared that “saying ‘no’ to housing will no longer be state sanctioned”.

The Judicial Hammer

When legislatures are truly paralyzed—unable to anger local constituencies—change often comes from courts. This provides political cover for difficult decisions.

Arkansas School Consolidation

For decades, Arkansas struggled with fragmented education. Small rural districts proliferated, draining resources and providing inequitable education. The legislature refused consolidation due to intense rural voter pressure viewing local schools as community hearts.

In 2002, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled in Lake View School District v. Huckabee that the state’s school funding system was unconstitutional—both inequitable and inadequate.

The court order provided political cover. Legislators could tell constituents, “I didn’t want to close your school, but the Supreme Court made me.” In response, the legislature passed Act 60, mandating administrative consolidation of any district with fewer than 350 students. District numbers dropped from 308 to 245, forcing efficiencies the political process couldn’t achieve alone.

Kansas Tax Reversal

Kansas provides a dramatic example of how breaking points trigger ideological reversals. In 2012, Governor Sam Brownback enacted massive tax cuts exempting pass-through businesses from income tax, arguing it would create economic boom.

The boom didn’t materialize. Revenues collapsed, leading to nine rounds of budget cuts, credit downgrades, and failure to meet Supreme Court education funding mandates.

By 2017, the system had broken. Voters elected a wave of moderate Republicans and Democrats forming a supermajority that voted to override the Governor’s veto and repeal tax cuts, raising $1.2 billion to stabilize budgets and schools.

The Ultimate Rupture: Insolvency

The most severe scenario involves total sovereignty loss when the “endless cycle” runs out of money.

In 1975, New York City effectively ran out of cash. Banks refused lending. The state intervened, creating unelected boards that took control of the city’s budget, forcing wage freezes, layoffs, and ending free tuition at CUNY. The local legislature was sidelined.

In 2013, Michigan appointed an Emergency Manager for Detroit who filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy. The resulting “Grand Bargain” allowed the city to shed $7 billion in debt but required massive concessions.

While states cannot declare bankruptcy like cities, the threat of this scenario often drives preemptive measures like Connecticut’s fiscal guardrails.

What Happens Next

The historical record reveals a consistent pattern: entrenched political systems don’t reform through gradual adjustment. The incentives maintaining the status quo are too strong to overcome through standard political pressure.

Instead, change requires disruption. The trajectory depends on who initiates it. Michigan-style calculated crises come from within legislatures willing to blow up existing systems. Connecticut-style fiscal guardrails arrive when external market forces—corporate departures, credit downgrades—become unbearable. Montana-style regulatory reform happens when specific crises unite unlikely coalitions. Arkansas-style judicial mandates occur when courts provide political cover for unpopular but necessary actions.

The common thread across all scenarios: systems change when the cost of stability exceeds the cost of reform. In Michigan, that cost was voter property tax revolt. In Montana, it was housing crisis paralyzing the economy. In Connecticut, it was General Electric and Aetna leaving the state.

For states facing similar challenges—whether education funding structures, regulatory deadlocks, or spending cycles—these historical patterns suggest the question isn’t whether rupture will occur, but which scenario will ultimately force it. The mechanisms vary, but the fundamental dynamic remains constant: entrenched systems break only when maintaining them becomes more painful than enduring the disruption of change.

Your report "When Waters Rise, Vermont’s Flood Warning Systems Help—If You’re Connected" put you on my radar a few weeks back and I left the tab open to revisit it when time became available. We in Rockbridge County, Virginia, have similar problems and concerns.

Today I became a free subscriber, and I'm getting to know you by reading more broadly.

This post ("Vermont Trapped in "Institutional Sclerosis": Lessons from States That Forced Radical Reform") is a model of clarity and efficiency. I'll soon be heading into my third reading.

Excellent Article. I believe Vermont is at the Inflection point.