Vermont Supreme Court Ruling Opens Door for PCB Lawsuits—But Leaves Some Students Behind

The admission of expert testimony from Dr. Kenneth Spaeth, who directed the World Trade Center Medical Monitoring Program, was significant.

A landmark decision from the Vermont Supreme Court has fundamentally changed who can sue Monsanto over PCB contamination in Vermont schools, while a funding crisis has left many buildings untested and students in legal limbo.

What the Court Decided

On December 12, 2025, the Vermont Supreme Court answered key questions about whether students exposed to toxic chemicals in their schools can force the chemical manufacturer to pay for lifetime medical monitoring. The ruling in Neddo v. Monsanto creates winners and losers among Vermont families—and the dividing line comes down to timing.

The case centers on Amber Neddo, who sued on behalf of her children and others who attended Vermont schools contaminated with Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). These chemicals, manufactured solely by “Old Monsanto” from 1935 to 1977, were used in fluorescent light ballasts, caulking, paints, and adhesives in schools built during that era.

The “Release” Question: Bayer Can’t Hide Behind State Lines

The first major question was whether Monsanto—now owned by Bayer—could avoid liability by claiming it never “released” PCBs in Vermont since it manufactured them in Alabama and Illinois.

The Court said no. The justices ruled that selling a toxic substance that eventually emits chemicals into Vermont classrooms constitutes a “release” in Vermont, even if the sale happened decades ago at a factory in another state. This “supply-chain liability” prevents companies from outsourcing environmental responsibility by using middlemen.

Who Can Sue: The July 2022 Dividing Line

The more complicated question involved timing. Vermont’s medical monitoring law (12 V.S.A. § 7202) took effect July 1, 2022. The Court ruled this law cannot be applied retroactively to people whose exposure ended before that date.

This creates what legal observers call a “donut hole”:

Who can sue: Current students, teachers, and staff who were in contaminated buildings after July 1, 2022, can join the class action for medical monitoring—a program requiring Monsanto to pay for regular cancer screenings and other health surveillance throughout their lives.

Who cannot: Former students who graduated before July 2022, or teachers and staff who left before that date, are excluded from the streamlined medical monitoring remedy. They would need to file traditional personal injury lawsuits proving actual physical harm—a much harder legal standard—rather than just increased risk of future disease.

What Are PCBs and Why Do They Matter?

PCBs are synthetic chemicals that were prized in construction for being fire-resistant and chemically stable. According to federal health agencies, they’re classified as probable human carcinogens and are linked to reduced IQ in children, attention deficits, thyroid problems, and weakened immune systems.

The chemicals accumulate in body fat over time and don’t break down easily. This makes schools particularly concerning exposure sites—children spend years breathing the same air as PCBs slowly volatilize (turn to vapor) from aging building materials.

Act 74: The Testing Mandate That Revealed the Problem

In 2021, Vermont became the first state in the nation to systematically search for PCBs in schools by passing Act 74. The law required all schools built or renovated before 1980 to test their indoor air for PCBs.

The results were alarming. According to data from the Department of Environmental Conservation, approximately 31% of tested schools exceeded Vermont’s “School Action Level,” requiring remediation. Twenty schools hit the “Immediate Action Level,” and seven required significant PCB removal or cleanup.

Vermont set stricter exposure limits than federal standards, recognizing that children breathe more air relative to their body weight and are more vulnerable to developmental toxins. For pre-K students, the action level is 30 nanograms per cubic meter of air; for K-6, it’s 60 ng/m³; and for older students and adults, 100 ng/m³.

The Funding Crisis: Testing Stops Mid-Program

Despite the mandate, the testing program has ground to a halt. A March 2025 update from Montpelier Roxbury Public Schools states bluntly: “funding is not currently available under the PCB testing program” to test Roxbury Village School or Montpelier High School.

This creates an inequitable situation. Schools that completed testing early—and found contamination—have spent money on remediation, air filters, and monitoring. Schools that haven’t been tested remain in use, with students and staff potentially exposed but without the data to prove it or trigger legal protections.

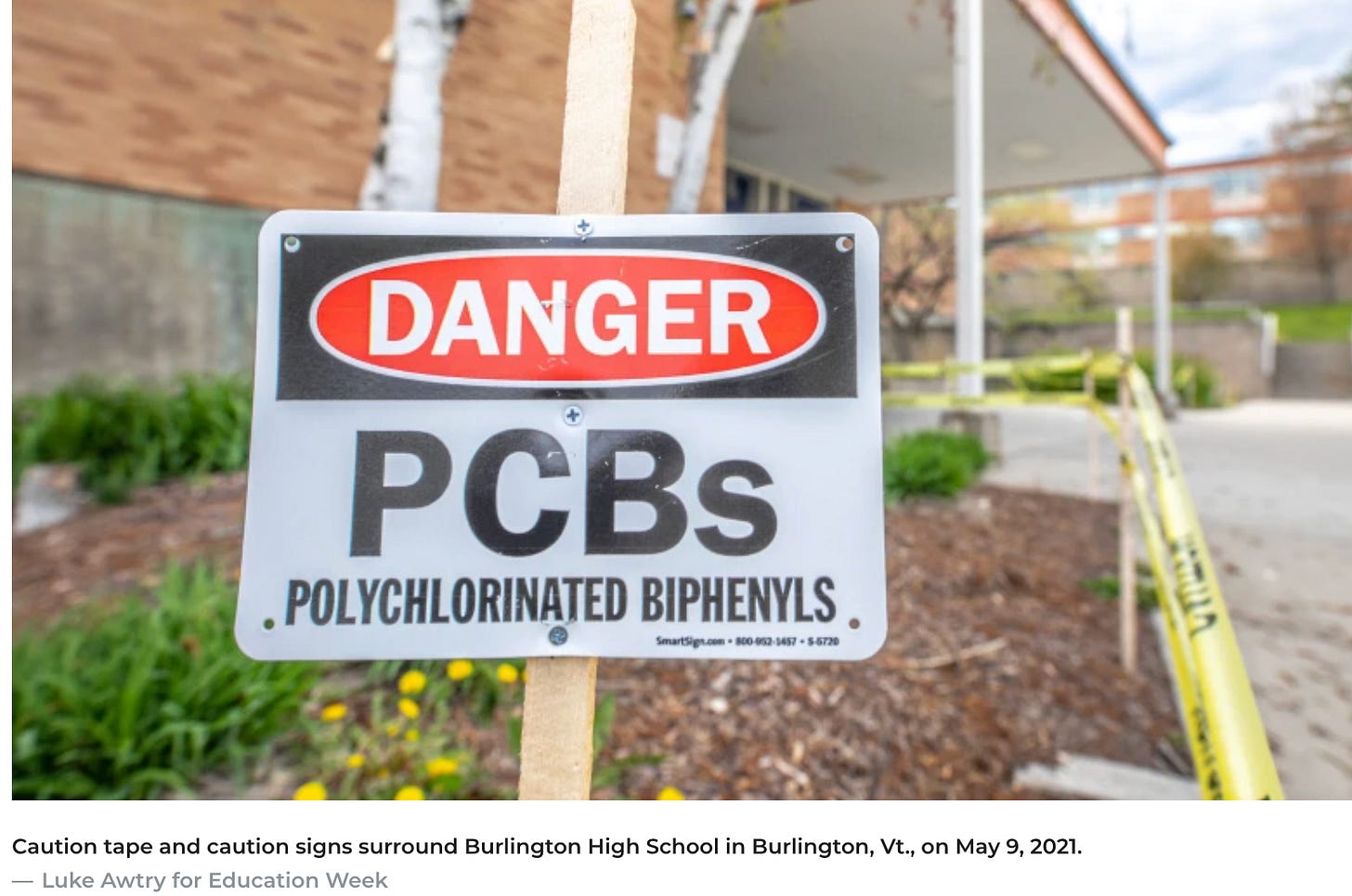

The most dramatic case involved Burlington High School, where severe contamination led to complete campus closure and demolition. The Burlington School District filed its own lawsuit seeking $190 million for a replacement building.

Bayer’s Defense Strategy

Bayer consistently emphasizes that “Old Monsanto voluntarily ceased production of PCBs in 1977,” two years before the federal ban, positioning the company as responsible. However, Vermont’s Attorney General alleges that internal company documents show Monsanto knew of PCB toxicity for decades but continued sales to maximize profits.

Bayer also frequently states that PCB levels in schools “fell well below regulatory health-protective limits.” This typically references older federal standards for adult industrial workers rather than Vermont’s stricter, pediatric-focused standards.

Additionally, Bayer has sued companies that purchased bulk PCBs in the 1970s—such as light ballast manufacturers—seeking to enforce “indemnification agreements” that would shift financial liability to these former customers.

The State’s Separate Fight

Vermont Attorney General Charity Clark filed a separate lawsuit against Monsanto in June 2023, seeking to recover the costs of the statewide testing and remediation program. The state’s suit aims to replenish the empty coffers that halted testing.

The AG’s office has requested that federal courts pause individual school district and class action lawsuits, arguing that piecemeal settlements could deplete resources needed for comprehensive statewide remediation. This has created tension with private attorneys representing individual students and districts, who argue their clients have immediate needs that can’t wait years for the state’s massive environmental case to conclude.

Legal Representation

The Neddo plaintiffs are represented by Edelson PC, a Chicago firm known for aggressive class action litigation, along with Montpelier’s Wilschek Iarrapino Law Office. On the defense, Bayer is represented by Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP and Sheehey Furlong & Behm P.C.

The admission of expert testimony from Dr. Kenneth Spaeth, who directed the World Trade Center Medical Monitoring Program, was significant. The federal judge allowed his testimony linking plaintiffs’ increased disease risk directly to school PCB levels, defeating Bayer’s argument that such claims are “speculative.”

What Happens Next

The case now returns to U.S. District Court in Vermont for trial on the merits. Meanwhile, several parallel tracks will unfold:

For current students and staff: If your school has tested positive for PCBs and you were present after July 1, 2022, you likely have standing to join the Neddo class action for medical monitoring.

For former students and pre-2022 graduates: You are excluded from the streamlined medical monitoring remedy and would need to prove actual physical injury in a traditional personal injury lawsuit.

For untested schools: You’re in limbo. Without test results confirming PCB levels, students cannot prove the “release” necessary to trigger legal protections under the Court’s ruling—meaning the testing freeze effectively limits the size of the potential plaintiff class.

Legislative action: The Vermont Legislature will need to address both the funding crisis to complete testing and potentially whether to extend medical monitoring rights to pre-2022 exposure victims, though the cost implications make this politically challenging.

Broader implications: The ruling’s broad definition of “release” could affect other toxic chemical litigation in Vermont, including cases involving PFAS “forever chemicals” in firefighting foam, food packaging, and other products.

As Attorney General Clark pursues the state’s case and the Neddo litigation moves toward trial, Vermont families are witnessing a test of whether the legal system can effectively address the toxic legacy of 20th-century industrial chemicals—and whether funding limitations will prevent full accountability.