Vermont Stands Alone: Lax Rules Let Lawmakers Accept Foreign Trips Banned Elsewhere

Vermont’s ethical framework is known as the “Swiss Cheese Model”—a system that is riddled with structural voids. These holes allow conduct that is strictly regulated or prohibited in other states.

The Erosion of the “Vermont Way”

For generations, the State of Vermont has governed itself through a philosophy known as the “Vermont Way.” Deeply rooted in the tradition of town meetings and citizen legislatures, this ethos operates on a simple, neighborly assumption: in a small state where constituents bump into their representatives at the grocery store or gas station, the fear of reputational shame is a stronger deterrent against corruption than any rulebook. Consequently, Vermont has historically operated with a patchwork of norms rather than a comprehensive statutory code of ethics, prioritizing accessibility over formal transparency.

However, the modern era of globalized political influence has placed immense strain on this localized honor system. Legal scholars and reform advocates now characterize Vermont’s ethical framework as “Swiss cheese”—a system that appears solid from a distance but is riddled with structural voids. These holes, when aligned, allow conduct that is strictly regulated or prohibited in other states.

This structural weakness was recently tested by the controversy surrounding the “50 States, One Israel” trip in September 2025. The event, where five Vermont lawmakers accepted travel expenses funded by a foreign government, serves as a catalyst for understanding how the state’s ethical laws function—and where they fail.1

The Catalyst: A $6,500 “Educational” Journey

In September 2025, five Vermont legislators—Representatives Sarah “Sarita” Austin, Matt Birong, Gina Galfetti, Will Greer, and James Gregoire—participated in a trip to Israel sponsored by the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs.2 The trip, valued at approximately $6,500 per person, included airfare, five-star lodging, and access to high-level officials.

Following the trip, the organization Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) filed formal ethics complaints against the lawmakers. The complaint alleges that accepting such high-value gifts from a foreign power constitutes a violation of ethical standards and opens the door to unregulated lobbying. The legislators have defended the trip as an official capacity “fact-finding” mission, arguing it provided necessary education on complex geopolitical issues.

Regardless of one’s stance on the conflict in Gaza, the incident acts as a forensic tool to examine the “Swiss cheese” effect in Vermont law. The ability of legislators to accept this funding without triggering immediate penalties or detailed public disclosure is not an accident; it is the result of specific legal loopholes.

The First Hole: The “Gift to the State” Loophole

The most significant structural void is found in Title 3, Section 1203g of the Vermont Statutes. While the law generally prohibits public servants from accepting gifts to prevent influence peddling, it contains a critical exception: “Gifts to the State.”

Under § 1203g(a)(2), a public servant may accept goods or services if they are for “use by the public servant while serving in an official capacity.” Legal interpretations of this statute allow legislators to categorize third-party funded travel not as a personal gift (which would be restricted), but as a gift to the State of Vermont.

The logic follows that because the legislator is learning about policy, the state is the beneficiary, even if the legislator is the one enjoying the flight and hotel. Because it is legally considered a benefit to the state, it often bypasses personal financial disclosure forms, leaving the public unaware of the financial transfer unless it is reported by the press.

The Second Hole: The Enforcement Blackout (Act 44)

Even if a complaint is filed, as JVP has done, it encounters a second structural void: a lack of enforcement power.3 In 2025, the legislature passed Act 44. Originally intended to strengthen the State Ethics Commission, the final version of the bill included a compromise that delayed the Commission’s investigatory powers until September 1, 2027.

This creates an “enforcement blackout.” Currently, the State Ethics Commission can receive complaints but lacks the statutory authority to subpoena witnesses, compel documents, or independently investigate the details of the Israel trip. Furthermore, due to chronic underfunding, the Commission operates with minimal staff, limiting its ability to provide proactive oversight.

Comparative Analysis: Vermont vs. The Rest

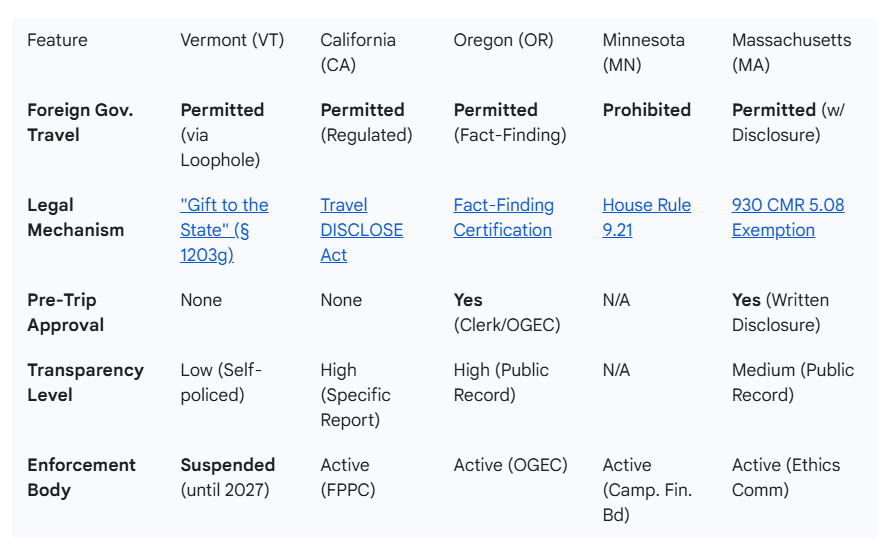

To understand how unique Vermont’s vulnerability is, it is helpful to compare its framework with other states that have faced similar issues of foreign influence. While Vermont relies on the “Gift to the State” exception, states like California and Minnesota have enacted rigorous statutes to close these specific holes.

Table 1: Comparative State Ethics Frameworks - Foreign Travel & Gifts

As the table illustrates, Vermont stands alone in combining a permissive legal environment (”Gift to the State”) with a suspended enforcement mechanism. In Minnesota, the trip would have been a violation of the gift ban. In California, it would require a specific disclosure report. In Vermont, it sits in the gray area of the “Swiss cheese.”

The “Black Box” of Legislative Self-Policing

Because the State Ethics Commission currently lacks the power to adjudicate complaints against legislators, the JVP complaint must be referred to the Legislative Ethics Panels. These are committees composed of the lawmakers’ own peers.

Critics, including the Vermont Political Observer, refer to these panels as “black boxes.” Unlike independent commissions, these panels operate under strict confidentiality rules. Historically, they provide little to no public information regarding their deliberations or the disposition of complaints. This creates a circular system where the only people authorized to judge the ethics of the legislature are the legislators themselves, operating under laws they wrote to include broad exceptions.

What Happens Next

The immediate future of the ethics complaint against the five lawmakers is procedural and likely quiet.

Referral: The State Ethics Commission will officially refer the JVP complaint to the House Ethics Panel.

Deliberation: The panel will meet, likely in closed session, to determine if the “Gift to the State” exception applies. Given the current phrasing of 3 V.S.A. § 1203g, a dismissal is a strong legal possibility.

Outcome: The public may receive a brief summary if a violation is found, but if the complaint is dismissed, the details may remain confidential.

Longer term, the 2026 legislative session presents a decision point. Legislators will face pressure to decide whether the “Vermont Way” can survive in its current form, or if the “Swiss cheese” holes—specifically the foreign travel loophole and the delay in Act 44 enforcement—need to be filled to prevent future influence operations from taking root in the Green Mountain State.

........"Lax Rules Let Lawmakers Accept Foreign Trips".......That should change...