Vermont Attorney General's Three Attempts to Sue Clearview AI End in Jurisdictional Dismissal

While Vermont’s lawsuit stalled, an earlier federal class-action case resulted in settlement giving plaintiffs, including Vermont, a 23% equity stake in Clearview AI, valued at about $51.75 million.

Vermont’s three-year legal battle to hold facial recognition company Clearview AI accountable for harvesting Vermonters’ photos from the internet has ended in dismissal, raising urgent questions about whether state consumer protection laws can keep pace with digital surveillance technology.

In December 2025, Washington County Superior Court Judge Daniel Richardson dismissed the state’s lawsuit, ruling that Vermont courts lack authority over the New York-based company because it has no physical presence, customers, or business operations in the state—even though its database likely contains images of hundreds of thousands of Vermonters.

What Clearview AI Does

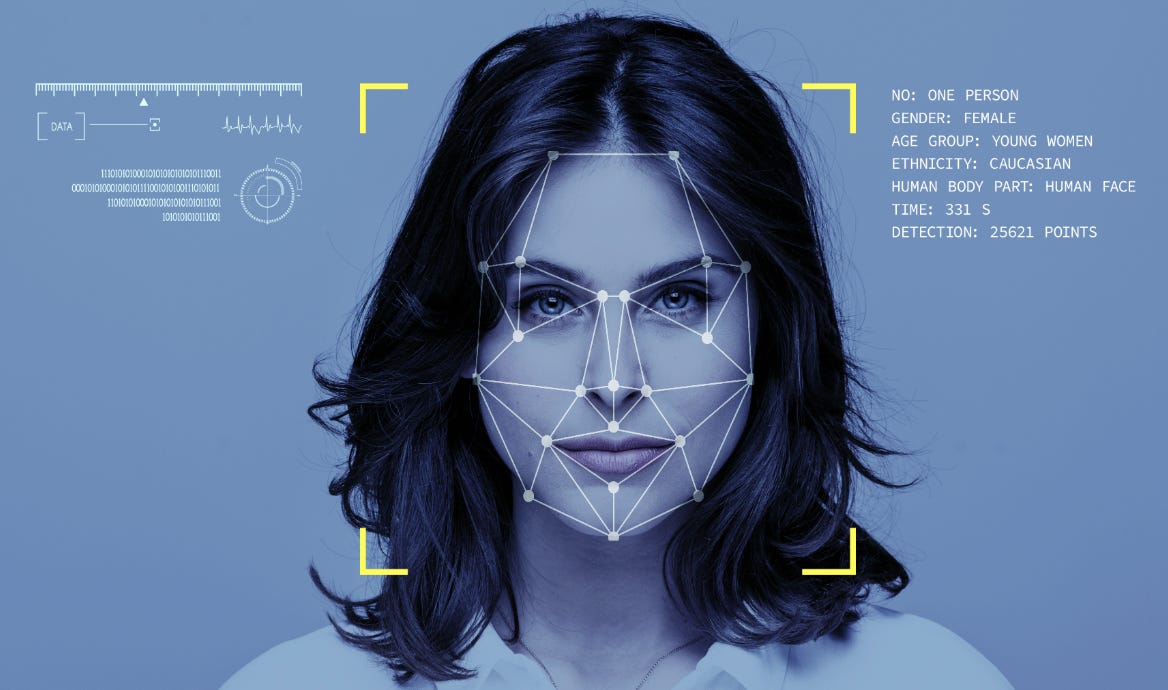

Clearview AI operates a massive facial recognition platform containing over 30 billion images scraped from publicly accessible websites, including social media platforms and professional networking sites. The company uses automated “crawlers” to harvest these photos without the knowledge or consent of the people in them.

The technology doesn’t just store photographs. It converts each face into a unique mathematical formula—essentially a digital fingerprint of your facial geometry. Law enforcement agencies and government contractors can then upload a photo to search the database and potentially identify anyone whose image has been scraped.

Unlike passwords or credit card numbers that can be changed if compromised, biometric data is permanent—you can’t change your face. According to the state’s original complaint, this creates a “permanent, inescapable virtual lineup” of individuals.

Three Attempts to Sue

Attorney General Charity Clark’s office has tried three separate times to hold Clearview accountable under Vermont’s Consumer Protection Act and laws against fraudulent data acquisition.

The first lawsuit, filed in Chittenden County in March 2020, was dismissed in 2023 on technical venue grounds—the court ruled the case was filed in the wrong county.

Clark refiled in Washington County in April 2025, arguing that state law allows the Attorney General to bring cases in the capital. The 21-page complaint sought a permanent injunction against the company, deletion of all Vermont residents’ data, restitution, and civil penalties of $10,000 per violation.

After a jurisdictional hearing in November 2025, Judge Richardson delivered the final dismissal.

Why the Judge Said No

The December ruling centered on a fundamental legal question: Can Vermont courts exercise authority over a company that has no offices, employees, or customers in the state?

Under constitutional law, courts can only force out-of-state defendants to appear if they have “minimum contacts” with the state—meaning they’ve purposefully conducted business there. Judge Richardson ruled that Clearview meets none of these criteria.

The court found that while Clearview likely possesses data on current Vermont residents, this connection is “random” and “fortuitous”—depending on where individuals choose to post photos online or where they happen to live, rather than any targeted activity by Clearview toward Vermont.

The judge distinguished Clearview from companies like Facebook or Amazon, which can be sued in Vermont because they have direct relationships with Vermont consumers. Clearview’s business model—taking data without providing any service to the people whose data is taken—ironically protects it from state court jurisdiction.

The Federal Settlement That Changed Everything

While Vermont’s lawsuit stalled, a massive federal class-action case in Illinois reached an unusual resolution. In March 2025, a federal judge approved a settlement giving plaintiffs a 23% equity stake in Clearview AI, valued at approximately $51.75 million.

The settlement structure is unprecedented in privacy litigation. Because Clearview claimed it lacked cash to pay a traditional settlement, the class recovery is tied to future “trigger events”—if the company goes public, is sold, or reaches certain revenue targets, class members receive their share.

A bipartisan group of 22 state attorneys general, including Clark, opposed this settlement, arguing it makes victims’ compensation dependent on the future profitability of the company they sued. The settlement also doesn’t require Clearview to stop scraping data or delete existing databases.

The federal court approved the settlement anyway, noting that separate litigation by the ACLU had already barred Clearview from selling its services to private entities—meaning only government agencies can now access the database.

The Privacy Bill That Almost Was

Following the December dismissal, Attorney General Clark called it a “call to the Legislature to act,” describing the ruling as a “classic example of technology outpacing the law.”

But Vermont’s recent attempt to pass comprehensive privacy legislation has already failed.

In early 2024, the Legislature passed H.121, the Vermont Data Privacy Act, which would have been one of the strongest privacy laws in the country. The bill included strict limits on data collection, special protections for children, and—most controversially—a private right of action allowing individuals to sue companies for violations.

Governor Phil Scott vetoed the bill in June 2024, arguing that the private lawsuit provision would make Vermont more “hostile than any other state” to businesses and non-profits. He suggested Vermont should adopt a more business-friendly approach similar to Connecticut’s law.

The House voted overwhelmingly to override the veto (128-17), but the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed, finishing 14-15.

What Clearview Says

Clearview maintains it doesn’t “operate” in Vermont in the legal sense—it has no physical presence or customers here. The company argues it’s simply a search engine for publicly available information, protected by the First Amendment.

There’s an irony in this position: Clearview is registered in Vermont’s Data Broker Registry, where it acknowledged collecting and selling personal information of Vermont consumers “with whom the business does not have a direct relationship.” The court’s ruling suggests that being a registered data broker in Vermont doesn’t create the legal contacts necessary for a lawsuit.

What Happens Next

Vermont now finds itself in a legal vacuum. Without the federal MDL settlement, which applies only to class members, most Vermonters have no direct recourse against Clearview. The state’s existing Consumer Protection Act—designed for traditional business relationships—has proven inadequate for companies that profit from residents without doing business with them.

The Legislature could revive privacy legislation in the 2026 session. Attorney General Clark has framed the court’s dismissal as evidence that statutory reform is essential. However, any new bill would likely face the same political dynamics that killed H.121—balancing privacy protection against concerns about Vermont’s business climate.

At the federal level, there is no comprehensive biometric privacy law comparable to Illinois’ statute that drove the class-action settlement. Until Congress acts, or until Vermont passes its own privacy statute, the state’s residents remain in what the Attorney General calls a jurisdictional gap: their facial data can be scraped, stored, and sold by companies that state courts are powerless to reach.

For now, the question of who controls Vermonters’ biometric data remains unresolved—caught between traditional legal boundaries that trace state lines and digital technologies that ignore them.

I'm really impressed with this stack. I reads like journalism should, without bias.