The Rest of the Story: Vermont Banned Cellphones in Schools, But Provided No Funding for Implementation

This contrast raises a critical question for Vermonters: If creating a distraction-free learning environment is a statewide priority, should its implementation be a shared statewide cost?

Vermont has officially joined a national movement, with Governor Phil Scott signing a bill last week that will ban student cellphone use in schools from bell to bell. The law, H.480, championed by a bipartisan consensus of lawmakers concerned about distraction, bullying, and mental health, is being hailed as a crucial step to help students focus and engage more directly with their peers and teachers.

But as the ink dries on the new law, a critical question looms over school districts across the Green Mountain State: Who is going to pay for it?

The new mandate, set to take effect for the 2026-27 school year, requires the Agency of Education to develop a model policy for schools to adopt. However, the legislation includes no funding to help schools implement it. This leaves local districts, many already navigating tight budgets and intense debates over statewide education financing, to foot the bill for what could be a costly logistical challenge.

This is the rest of the story.

The Unfunded Mandate: A Costly Proposition

For schools, implementing an effective phone-free policy is far more complex than simply telling students to put their devices away. Experience from districts across the country shows that without robust systems, enforcement devolves into a frustrating and often futile "cat-and-mouse game" for teachers, draining valuable class time. The most common solutions, however, carry significant price tags.

The potential costs of implementation that now fall to local districts include:

Lockable Pouch Systems: These have become a popular, high-tech solution. Each student is issued a pouch, like those from the company Yondr, that locks magnetically upon entering school. The pouch is only opened at unlocking stations at dismissal. For a medium-sized Vermont high school with 500 students, the upfront cost for such a system could easily run into the tens of thousands of dollars, plus recurring costs for staff time and replacing damaged or lost pouches.

Classroom-Based Storage: A lower-tech option involves purchasing "phone jails" or numbered caddies for every single classroom. While less expensive than pouches, this still represents a new, unbudgeted expense for hundreds of classrooms across a district, requiring a consistent process from every teacher.

Staffing and Administrative Time: Regardless of the system, enforcement requires staff time. This is time spent collecting, storing, and redistributing hundreds of phones a day. It's administrative and teacher time that is not being spent on instruction, lesson planning, or direct student support.

This unfunded mandate arrives as Vermont schools are already at the center of a tense fiscal conversation. Lawmakers and communities are grappling with skyrocketing education costs, driven by factors like healthcare expenses and the need for special education services. Passing a new statewide rule without allocating funds places the financial and logistical weight squarely on the shoulders of local communities. This risks creating an equity issue, where wealthier districts can afford effective, high-tech solutions while less-resourced schools are left with honor-system policies that are much harder to enforce.

Lessons From Other States: The Value of Investment

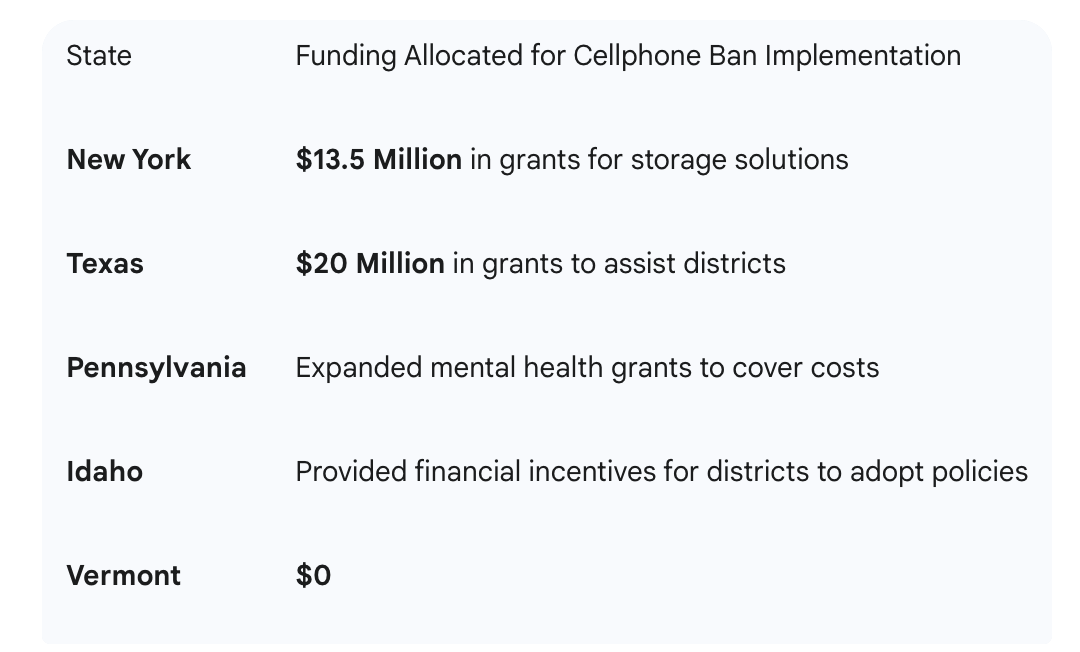

Vermont is not the first state to walk this path, but it is one of the few to do so without dedicating state funds to the effort. Other states that have passed similar bans have recognized the implementation costs and stepped up to help their schools succeed.

New York, for instance, allocated $13.5 million to help schools purchase storage solutions for their bell-to-bell ban. Texas included $20 million in grants for districts to get their programs off the ground. Others, like Pennsylvania and Idaho, have used financial incentives to encourage, rather than mandate, districts to go phone-free.

These states recognized that funding is not just about buying equipment; it's about ensuring the law is applied effectively and equitably for all students.

This contrast raises a critical question for Vermonters: If creating a distraction-free learning environment is a statewide priority, should its implementation be a shared statewide cost?

As it stands, the success of Vermont's new law may depend less on the intentions of the legislature and more on the ability of individual school districts to find room in their already strained budgets to turn a well-meaning policy into a workable reality.

A National Movement: The State of Cellphone Bans

A common question is whether Vermont is an outlier or part of a larger trend. Indeed, the move to restrict cellphones in schools is a powerful national movement.

Roughly half of all states in the U.S. now have laws or statewide rules that ban or regulate student cellphone use during the school day. This reflects a broad, bipartisan consensus that the devices are a significant impediment to learning and a detriment to youth mental health.

While a completely exhaustive and continuously updated list is difficult to maintain due to the rapid pace of legislation, as of mid-2025, at least 26 states have passed specific laws. The policies vary, with some banning phones "bell-to-bell" and others restricting them only during instructional time.