The Ground Beneath Our Feet: Why a Minor Tremor is Vermont's Wake-Up Call

The true danger for Vermont lies not in the probability of an earthquake, but in the catastrophic consequences a moderate one could have on the state’s beloved historic brick buildings.

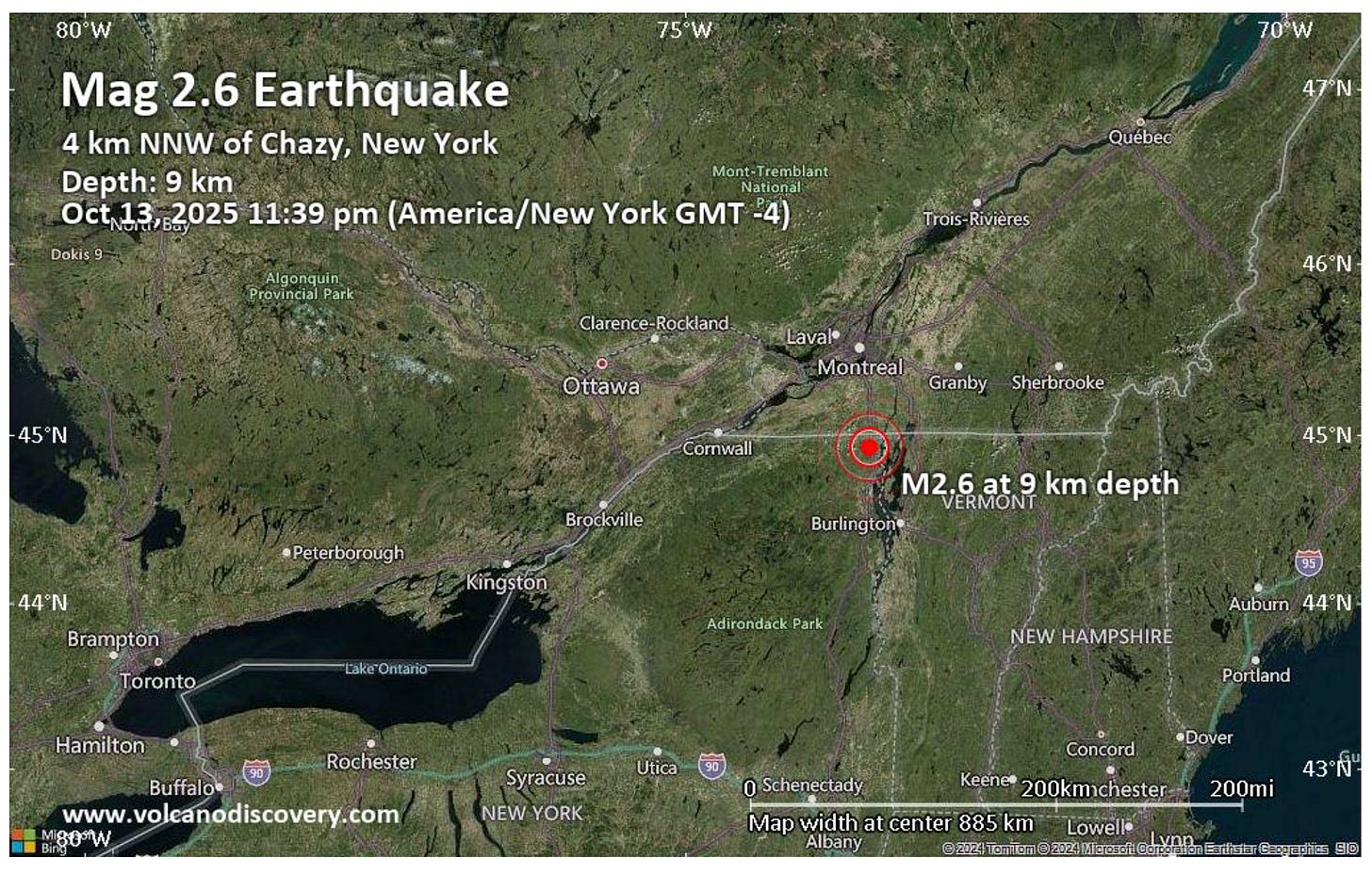

A faint, late-night rumble on October 13, 2025, served as a potent reminder to Vermonters: the famously stable ground of the Green Mountain State is not entirely still.

The magnitude 2.6 earthquake, centered near Chazy, New York, caused no damage but rattled nerves and sparked a conversation. While the event was minor, it highlighted an ancient fault line, a history of regional shaking, and a specific, tangible risk hiding in plain sight in Vermont’s historic downtowns.

This was not a warning of impending doom, but rather a low-cost, high-value drill. It presents a clear choice for the state: to continue with a false sense of security or to embrace a culture of preparedness.

Anatomy of a Minor Quake

The tremor that woke residents across the Champlain Valley was scientifically documented with precision. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the earthquake struck at 11:39 p.m. and originated at a relatively shallow depth of about 5.4 miles. This shallow focus is key; it means the seismic waves had less distance to travel before reaching the surface, which is why a small magnitude 2.6 event was felt so distinctly by so many people.

The human experience was captured by the USGS’s “Did You Feel It?” program, which gathered over 226 public reports. The feedback from residents in Vermont and New York allowed scientists to assign the quake a maximum Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) of III. Unlike magnitude, which measures the energy released at the source, intensity describes the shaking effect at a specific location. An MMI of III is classified as “weak,” with vibrations similar to a passing truck, enough to be noticeable but not damaging.

While this event was the largest to originate in northern New York in 2025, according to WCAX, it pales in comparison to the region’s more powerful seismic history. The 1944 magnitude 5.8 Cornwall-Massena earthquake caused widespread damage, and a magnitude 5.0 quake near Plattsburgh in 2002 also rattled the region significantly. The Chazy tremor was merely a faint echo of the forces that lie dormant beneath the surface.

The Ghost in the Bedrock: The Champlain Thrust Fault

The recent tremor was linked to the Champlain Thrust Fault, a colossal scar in the Earth’s crust stretching over 200 miles from Quebec to the Catskills. This is not a new or “reawakening” fault in the way many might imagine. According to geologists, it was formed approximately 450 million years ago when a volcanic island arc collided with ancient North America. The immense force of that collision shoved a massive slab of older rock dozens of miles westward, pushing it up and over a layer of younger rock. This ancient structure is a pre-existing zone of weakness embedded deep within the North American Plate.

Today, the entire continent is under a slow, steady compressive stress, primarily driven by the spreading of the seafloor at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This stress builds over time and occasionally finds a release point along one of these ancient zones of weakness. The Chazy quake was just that: a tiny, instantaneous release of accumulated strain. It confirms the fault is a feature that can release energy, but it does not change the long-term, low probability of a major event.

A crucial factor for Vermonters is the very nature of the region’s bedrock. The old, cold, and solid crust of the Northeast is exceptionally efficient at transmitting seismic energy. This is why the small Chazy quake was felt hundreds of miles away and why the 2011 Virginia earthquake was felt up and down the East Coast. This means any future, more significant earthquake in the region will have a much wider impact zone than a similar-magnitude event in a place like California, a critical fact for emergency planning.

The Real Risk: When Old Bricks Meet New Shaking

While Vermont has very few earthquakes centered within its borders, its primary seismic hazard is an imported one. The state has been repeatedly shaken by larger quakes in New York, Quebec, and New Hampshire. This history of imported shaking is the basis for Vermont’s official seismic hazard maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). These maps place the populous northwestern corner of the state, including Chittenden County, in Seismic Design Category C, an area that “could experience strong shaking.” The rest of the state is in Category B, which could see moderate shaking.

The true danger for Vermont lies not in the probability of an earthquake, but in the catastrophic consequences a moderate one could have on the state’s most beloved structures: its historic brick buildings. The downtowns of Burlington, Montpelier, Brattleboro, and countless other communities are defined by buildings made of unreinforced masonry (URM).

Constructed before modern seismic codes, these buildings have critical, life-threatening flaws:

Brittleness: The brick and mortar can snap suddenly under the side-to-side stress of an earthquake.

Poor Connections: Floors and roofs often just rest in pockets in the brick walls. During shaking, the heavy walls can pull away, leading to a total collapse.

Falling Hazards: Heavy parapets, chimneys, and cornices can easily break loose and fall onto sidewalks below, posing a lethal threat to pedestrians.

A 2018 study requested by the Vermont Geological Survey estimated there may be more than 3,000 of these vulnerable URM buildings in Chittenden and other counties. They are concentrated in the very downtown cores that are the economic and social hearts of our communities. The very architecture that gives Vermont its historic charm is also its greatest seismic liability.

From Worry to Action: A Path to Resilience

The October 13th earthquake does not warrant worry, which is a passive emotion. It demands preparation, which is an active response. Addressing Vermont’s seismic risk requires a two-pronged approach that empowers both individuals and government.