The Catamount Conundrum: The Pros and Cons of Reintroducing a Native Predator to Vermont

In the rolling Green Mountains of Vermont, the idea of bringing back the catamount—also known as the cougar, puma, or mountain lion—has sparked a lively debate.

Once a native predator, the last confirmed catamount was killed in 1881, its taxidermied remains a somber exhibit at the Vermont History Museum in Montpelier. Now, a 2025 legislative proposal, bill H. 473, calls for a feasibility study to explore reintroducing this apex predator, due by January 2027.

While the prospect of restoring a cultural and ecological icon excites some, it raises concerns about feasibility, cost, and competing priorities in a state grappling with housing shortages, rising homelessness, and education funding disputes. As Vermont weighs this bold conservation effort, a pressing question emerges: where do Vermont’s human residents fit amidst these ambitious initiatives?

The Case for Reintroduction: Ecological and Cultural Benefits

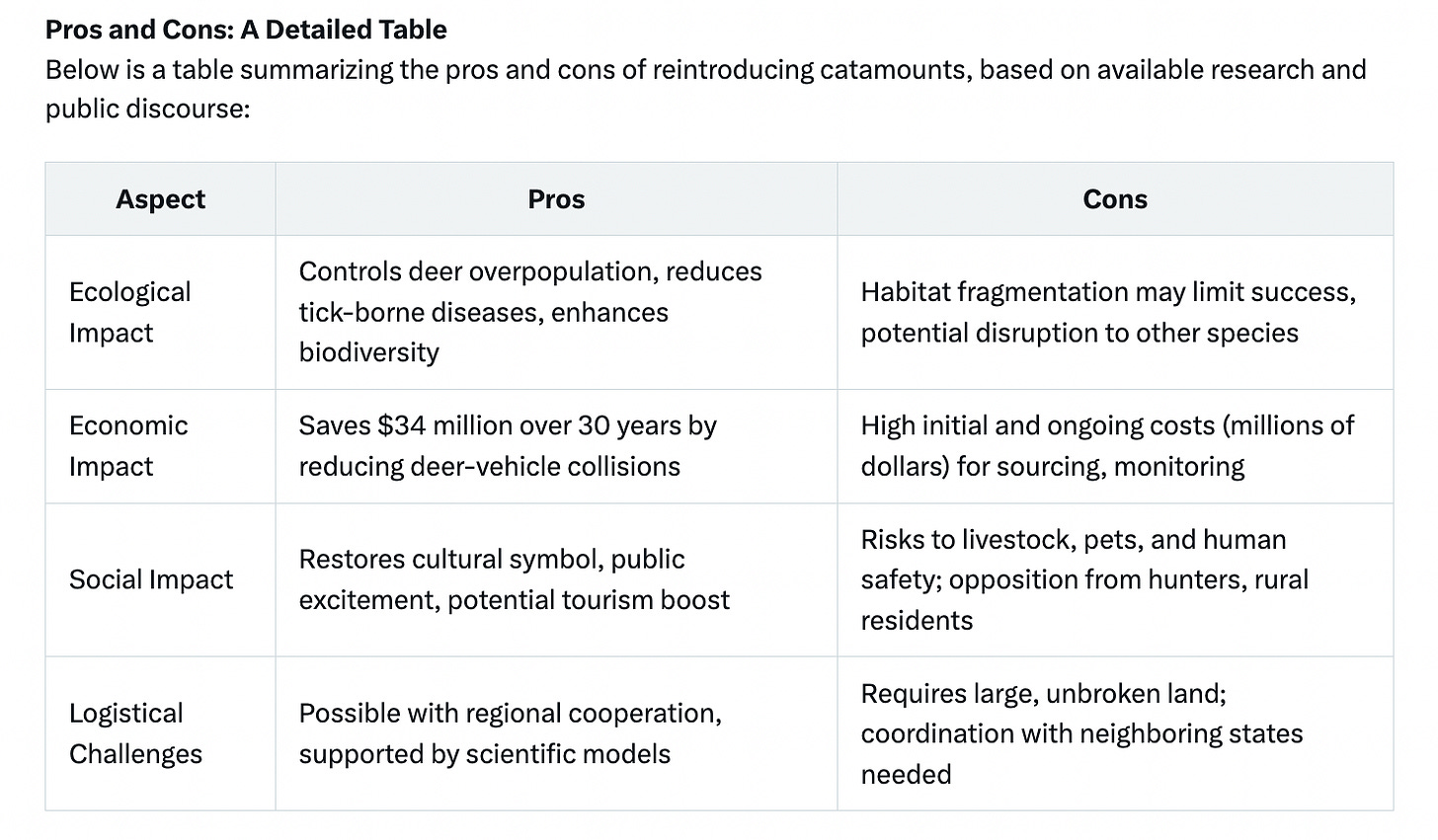

Proponents of reintroducing catamounts argue it could restore ecological balance and revive a piece of Vermont’s heritage. A 2016 study in Conservation Letters suggests cougars could reduce deer-vehicle collisions by 22%, preventing over 11 deaths and saving $34 million in Vermont over 30 years by curbing deer overpopulation. This is significant in a state where deer contribute to habitat degradation, tick-borne diseases like Lyme, and costly accidents. In areas like South Dakota, growing cougar populations have lowered collision costs by $1.1 million annually, hinting at similar potential for Vermont.

Beyond ecology, catamounts hold cultural weight. As the mascot of the University of Vermont, they symbolize the state’s rugged spirit, immortalized in a bronze statue on campus. Advocates like Rep. Sarah Austin (D-Colchester), who introduced H. 473, see their return as a way to honor this legacy while addressing modern environmental challenges.

The Challenges: Scientific, Social, and Economic Hurdles

Despite these benefits, reintroducing catamounts faces significant obstacles. Scientifically, Vermont’s habitat may not suffice. A 2022 Panthera study found suitable habitat south of Interstate 89 spans just under 12,000 square kilometers—barely enough to support a genetically diverse population. Catamounts require vast, unbroken forests, and Vermont’s patchwork of farms, towns, and roads complicates their survival. Coordination with neighboring states is also critical, as these wide-ranging predators would roam beyond Vermont’s borders, requiring a regional approach.

Socially, public opinion is divided. While some embrace the ecological and cultural arguments, others fear risks to livestock, pets, and human safety. A 2016 Vox article estimated cougars could cause one human death and five injuries annually in the eastern U.S., alongside impacts on deer hunting, a valued tradition in rural Vermont. Farmers and rural residents, already strained by economic pressures, worry about livestock losses, recalling the 19th-century conflicts that led to the catamount’s extinction. Vermont Fish and Wildlife officials, including former Commissioner Louis Porter, have historically opposed reintroduction, citing these concerns and the challenge of finding suitable territory.

Economically, the costs are daunting. Though exact figures await the feasibility study, reintroduction could cost millions for sourcing animals from western U.S. populations, transport, monitoring, and conflict management. The failed Florida panther reintroduction in the 1990s, which faced high costs and public resistance, serves as a cautionary tale. For a state already stretched thin, these expenses raise questions about priorities.

Vermont’s Human Priorities: A State Under Strain

Vermont’s pursuit of ambitious initiatives like catamount reintroduction must be viewed against its pressing human challenges. The state faces a housing crisis, with a 2024 report noting a shortage of over 24,000 affordable homes, driving up costs and exacerbating homelessness, which increased by 14% from 2022 to 2024. Education funding is another flashpoint, with property tax hikes sparking debates over how to sustain schools without burdening residents. Recent flooding and climate adaptation efforts further strain budgets, leaving many Vermonters asking: where do we fit in?

These challenges highlight a tension between conservation and human welfare. While reintroducing catamounts could yield long-term ecological and economic benefits, the immediate costs and risks compete with urgent needs like housing and education. Rural communities, already feeling overlooked, may resist an initiative perceived as prioritizing wildlife over people.

Striking a Balance: Is It Worth It?

The debate over catamount reintroduction encapsulates Vermont’s broader struggle to balance its environmental ethos with human realities. The ecological case is compelling—fewer deer-related accidents, healthier ecosystems, and a restored native species. Yet the scientific, social, and economic barriers are formidable, and the state’s limited resources amplify the stakes. The feasibility study mandated by H. 473 will clarify costs and logistics, but its success hinges on public buy-in and regional cooperation.

For now, the effort remains in early stages, with H. 473 unlikely to pass this session. This pause offers a chance to engage Vermonters in a broader conversation: how can the state pursue bold conservation goals while addressing housing, homelessness, and education? Initiatives like public forums or pilot programs could build trust, ensuring rural voices are heard alongside urban and environmental advocates. Without this, reintroduction risks becoming another well-intentioned idea that overlooks the people it aims to serve.