Standing Trees Group Challenges Welch Over Vote on Forest Health and Fire Prevention Measure

A sweeping piece of federal legislation working its way through Congress would fundamentally change how the U.S. government manages public forests — with real implications for Vermont.

What Is the Fix Our Forests Act?

The Fix Our Forests Act (FOFA), introduced as S. 1462 in the Senate and H.R. 471 in the House, is framed by its bipartisan sponsors as an urgent response to the nation’s escalating wildfire crisis, citing the 2018 Camp Fire, the 2023 Lahaina fires, and the 2025 Los Angeles fires as catalysts. While its origins lie in western wildfire conditions, the bill applies to all National Forest System lands — including Vermont’s Green Mountain National Forest.

The bill has four parts: large-scale forest restoration (the most controversial section), community protection in wildland-urban areas, technology and monitoring partnerships, and support for wildland firefighters.

Vermont’s Forest Baseline — Context That Often Gets Lost

Vermont is one of the most heavily forested states in the nation, with roughly 76% tree cover. The state has made enormous investments in land conservation, and the 2023 Act 59 sets formal goals of conserving 30% of Vermont’s land by 2030 and 50% by 2050. That baseline matters: Vermont is not a state on the verge of losing its forests. It is a state trying to balance one of the most protected landscapes in America with the real economic needs of its residents — including a severe housing shortage and rural communities that depend on a working forest for their livelihoods.

The Core Controversy: Environmental Review and Legal Challenges

The most debated provisions involve the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Currently, projects with minimal environmental impact can bypass detailed review through “Categorical Exclusions.” FOFA would raise the acreage limit for those exclusions from 3,000 to 10,000 acres per project. Supporters say land managers need to work at a scale that meaningfully reduces wildfire risk. Critics worry that 15 square miles without comprehensive review risks unintended ecological harm — though the bill retains language requiring projects to maximize retention of old-growth trees and rely on the best available science.

The bill would also reduce the statute of limitations for legal challenges from six years to 150 days and limit courts’ ability to pause projects during litigation. Conservation groups call this stripping public oversight. Proponents counter that roughly 1.8 billion board feet of federal timber sales are currently frozen in legal challenges, and that indefinite procedural delay is itself a policy outcome with real costs.

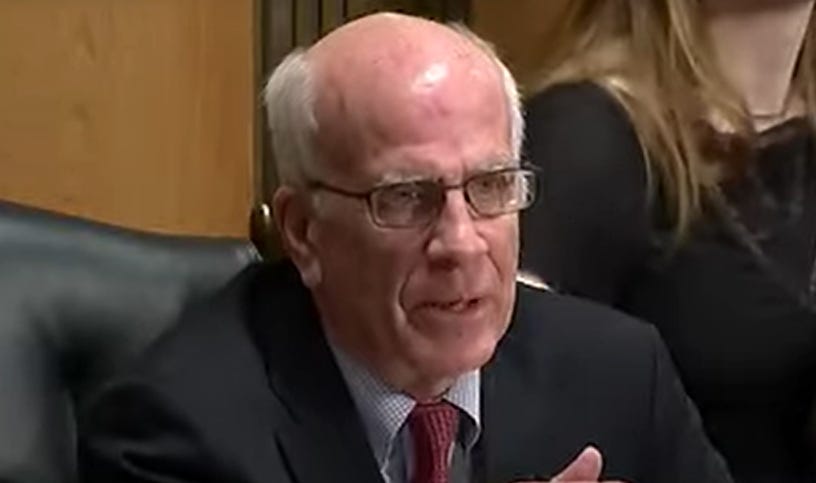

Senator Welch’s Vote: Strategy or Broken Promise?

The debate became local when Senator Peter Welch, a member of the Senate Agriculture Committee, shifted his position on the bill. In July 2024, he wrote that the legislation “seeks to weaken critical environmental laws” and concluded: “I cannot support this bill as written.” By October 2025, he voted to advance it out of committee in an 18-5 bipartisan vote, joining all Republican members and several Democrats including Ranking Member Amy Klobuchar.

Welch’s office described the vote as a strategic move to keep the Senator at the table and push for improvements during the full Senate floor process — a standard legislative approach. A “yes” in committee is frequently a vote to keep negotiating, not a final endorsement. The five Democrats who voted no — including Adam Schiff and Cory Booker — chose a different strategy, preserving a cleaner record at the cost of influence over the bill’s final form. Both approaches carry genuine trade-offs, and experienced legislators disagree about which produces better outcomes.

The Conservation Groups’ Position — and the Pushback It Faces

Standing Trees and the Vermont Sierra Club have called Welch’s justifications “hollow” and framed his vote as a betrayal. Their ecological argument — that mature, undisturbed forests are more fire-resistant, store more carbon, and protect watersheds better than managed stands — has legitimate scientific support and deserves serious consideration.

But critics of that posture, including many who share its environmental values, point to a consistent pattern: aggressive use of litigation and procedural delay to block active forest management, combined with opposition to housing development that contributes to Vermont’s affordability crisis. In a state that is already 76% forested, with robust permanent protections in place, arguments that any commercial activity on federal forest land is categorically unacceptable — while also resisting the housing construction that would help Vermont’s most vulnerable residents — strike many as a position that prioritizes environmental purity over the people living here.

Not all environmental voices agree. The Citizens’ Climate Lobby has expressed conditional support for FOFA, arguing bipartisan cooperation is the only realistic path to wildfire reform. The Western Governors’ Association also supports the bill. These are not fringe positions.

The Housing Connection

Vermont’s housing crisis adds an underappreciated dimension to this debate. Timber is a direct input to construction costs, and a 25% tariff on Canadian lumber imports has already added roughly $9,200 to the cost of a new single-family home. The Vermont Forest Products Association represents mills, loggers, and haulers whose sector has contracted more than 40% in recent years. A functional domestic timber industry — supported by reasonable access to federal timber supplies — is not separate from Vermont’s housing problem. It is connected to it.

The Science — and Vermont’s Unique Fire Profile

Proponents argue that a century of fire suppression has left forests dangerously overcrowded, pointing to data that California’s forests now average over 300 trees per acre versus a historical 64. Critics counter that thinning can sometimes increase fire risk by drying out the forest floor and generating flammable logging debris.

Both sides acknowledge that Vermont’s fire ecology is fundamentally different from the West’s. Major fire events here are rare; wind, ice, and flooding are the primary disturbance forces. That difference is central to the question of whether FOFA’s western-oriented provisions make sense applied uniformly to the Green Mountain National Forest.

What’s at Stake Locally

The Telephone Gap Integrated Resource Project — targeting 72,000 acres in the Rochester Ranger District — illustrates how these debates play out on the ground. After public opposition to initial clear-cutting proposals, the Forest Service adopted a compromise “triad approach”: some areas permanently protected, some for timber harvesting, some managed for old-growth development. Activists raise legitimate concerns about the age of trees in the project area. The timber industry notes the project supports local mills and the families depending on them. Both are true simultaneously.

What Happens Next

FOFA has cleared the Senate Agriculture Committee and is positioned for a full floor vote, with no date set. Senator Welch has indicated he will use the floor process to push for stronger environmental protections. Vermont conservation groups have vowed to keep public pressure on him to reverse course entirely.

For Vermont, the deeper challenge is one no single bill resolves: how to manage a working landscape that is simultaneously an ecological asset, an economic resource, a carbon sink, and the foundation of communities that need affordable housing and good jobs. Senator Welch’s committee vote reflects the difficulty of that challenge. Whether his inside strategy produces a better bill — or whether the conservation movement’s harder line better protects Vermont’s forests — is a question that the full Senate vote will begin to answer.

The full text of the Senate bill is available at Congress.gov.