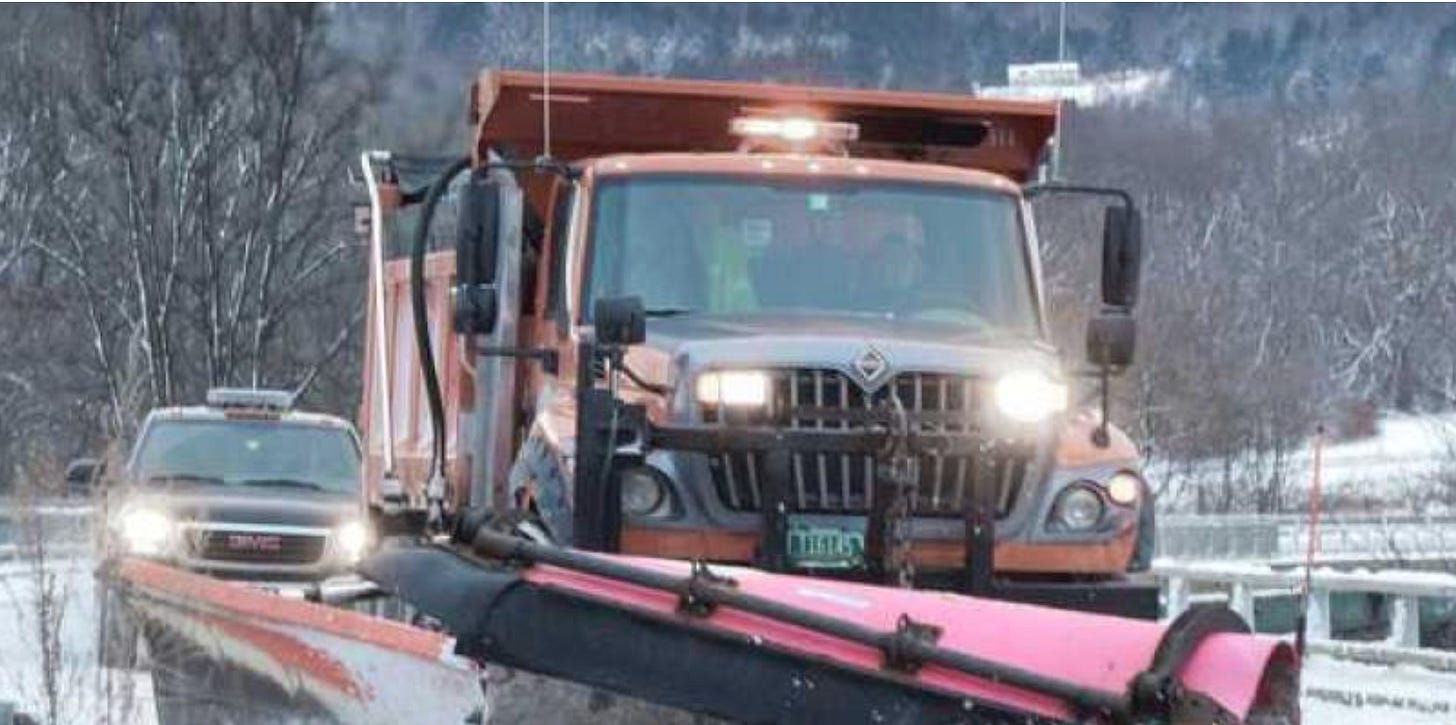

No Slips, Less Salt: Sea Grant and UVM Map Smarter Winter Practices for Chittenden County

The release of a new digital initiative this week has brought renewed focus to a quiet but growing environmental crisis in Vermont’s most populous county: the salination of local waterways.

On December 19, Lake Champlain Sea Grant announced the launch of the “Chittenden County Road Salting Practices” StoryMap. Designed by researchers at the University of Vermont (UVM) and FluidState Consulting, the tool aggregates data from eleven municipalities to highlight how towns are managing winter roads.

While the project is presented as an educational resource, a closer look at state and federal data reveals it arrives amidst a tightening regulatory landscape.

With seven local streams now listed as “impaired” due to chloride levels and a new federal mandate in effect for Colchester, the StoryMap serves as both a resource and a roadmap for compliance in an era where “clean water” and “safe roads” are increasingly at odds.

The Science: Why Salt Doesn’t Just Go Away

To understand the urgency behind the initiative, residents must first understand the chemistry of the problem. Road salt is primarily sodium chloride. Unlike other pollutants such as phosphorus, which can be absorbed by plants or settle into soil, chloride is a “conservative” ion. It does not break down, biodegrade, or disappear.

Once salt dissolves into snowmelt, it infiltrates the groundwater. This creates a “legacy effect” where chloride stored in the soil during winter seeps back into streams during dry summer months. Consequently, toxic spikes often occur long after the plow trucks have been parked for the season.

This biological impairment threatens freshwater organisms. According to Vermont Water Quality Standards, prolonged exposure to chloride levels above 230 mg/L stunts the growth and reproduction of aquatic life. In some urban streams, levels have spiked above 860 mg/L—a threshold considered acutely toxic.

The “Seven Streams” and Federal Mandates

The press release notes that Chittenden County currently has seven streams listed as impaired for chloride. This designation is not merely a label; it triggers legal requirements under the Federal Clean Water Act.

The most critical development occurred in June 2024, when the EPA approved a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for Sunnyside Brook in Colchester. A TMDL acts as a “pollution diet,” legally mandating reductions in pollutant loading. Sunnyside Brook, which drains a heavily developed area including I-89, acts as a regulatory bellwether for the region.

Other waterbodies on the state’s priority list facing similar challenges include:

Potash Brook (South Burlington): Drains a dense commercial corridor.

Centennial Brook (Burlington/South Burlington): Has recorded median chloride values as high as 716 mg/L.

Englesby Brook (Burlington): Has historically exceeded acute toxicity standards.

Muddy Brook (Williston), Bartlett Brook (South Burlington), and Morehouse Brook (Winooski/Colchester).

Technology as a Solution

The new StoryMap focuses on bridging the gap between current habits and sustainable technology. Dr. Kris Stepenuck, the lead researcher behind the project, utilized interviews with road foremen to identify specific technologies that reduce waste without compromising safety.

1. Pavement Temperature Sensors Salt loses effectiveness rapidly as temperatures drop. Below 15°F, rock salt is virtually ineffective. By installing infrared sensors on trucks, operators can measure the actual road temperature rather than the air temperature, preventing them from spreading material that won’t melt ice.

2. Segmented Plows Traditional plow blades are rigid and often ride over the top of ruts in the road, leaving packed snow that turns to ice. Segmented plows feature independent sections that contour to the road surface. This mechanical removal significantly reduces the need for chemical melting agents.

3. Brine and Pre-Wetting One of the most effective strategies involves dissolving salt into a liquid “brine” before application. This prevents the “bounce and scatter” effect where dry salt careens off the road into ditches. The StoryMap highlights the Town of Hyde Park, which achieved a 40% reduction in salt usage by adopting these liquid technologies, demonstrating that significant reductions are operationally feasible.

The Liability Gap: The Private Sector Factor

While the StoryMap provides a toolkit for municipal compliance, a significant portion of chloride pollution remains unaddressed by these efforts: the private sector.

Research indicates that private contractors—plowing parking lots, driveways, and condominiums—may contribute up to 50% of the chloride load in urbanized watersheds like Potash Brook. Unlike municipal crews, private contractors are often incentivized to over-salt due to liability concerns. This phenomenon is known as the “crunch factor,” where pedestrians perceive a surface as unsafe unless they can hear salt crunching underfoot.

Attempts to address this legislative gap stalled during the 2024-2025 session. Bill S.29, which proposed a voluntary certification program offering limited liability protection to contractors who followed best management practices, did not pass the Senate Committee on Judiciary. Without this protection, many contractors remain hesitant to reduce salt application rates, fearing negligence lawsuits from slip-and-fall accidents.

What Happens Next

The release of the StoryMap provides municipalities with the technical resources needed to begin complying with the new Sunnyside Brook TMDL and existing MS4 permit requirements. Residents can expect to see more towns adopting liquid brine systems and “live edge” plows in the coming winters.

However, with the legislative failure of liability reform for private contractors, the region faces a split reality: increasingly sophisticated salt management on public roads, contrasted with continued heavy application on private lots. Monitoring by the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation will continue, determining whether municipal efforts alone are enough to lower the toxicity of Chittenden County’s streams.

Great Article. Astonished it's taken this long to realize the problems...