More Than Morels: Inside Vermont's Booming Foraging Scene

If you've stumbled upon the "Vermont Foragers" Facebook page lately, you've seen it: a vibrant community 16,000 members strong, sharing tips, celebrating finds, and asking, "Can I eat this?" This digital campfire is just the most visible sign of a truth many of us feel in our bones—foraging in Vermont isn't just a niche hobby; it's a deeply ingrained part of our culture. It’s a treasure hunt that reconnects us to the woods, a way to stock our pantries, and a powerful force for building community across the state.

The act of gathering wild food is a practice that taps directly into the Vermont ethos of self-sufficiency and environmental stewardship. For some, it’s about the thrill of the hunt, the "childhood sense of wonder" that comes from discovering a patch of chanterelles. For others, it's a quiet act of rebellion against the industrial food system, a way to eat locally and sustainably. At its core, the culture balances a fascinating contradiction: the intense secrecy of a prized morel spot passed down through generations, and the open, welcoming spirit of sharing knowledge and harvests with friends, family, and thousands of strangers online.

The Green Mountain Pantry

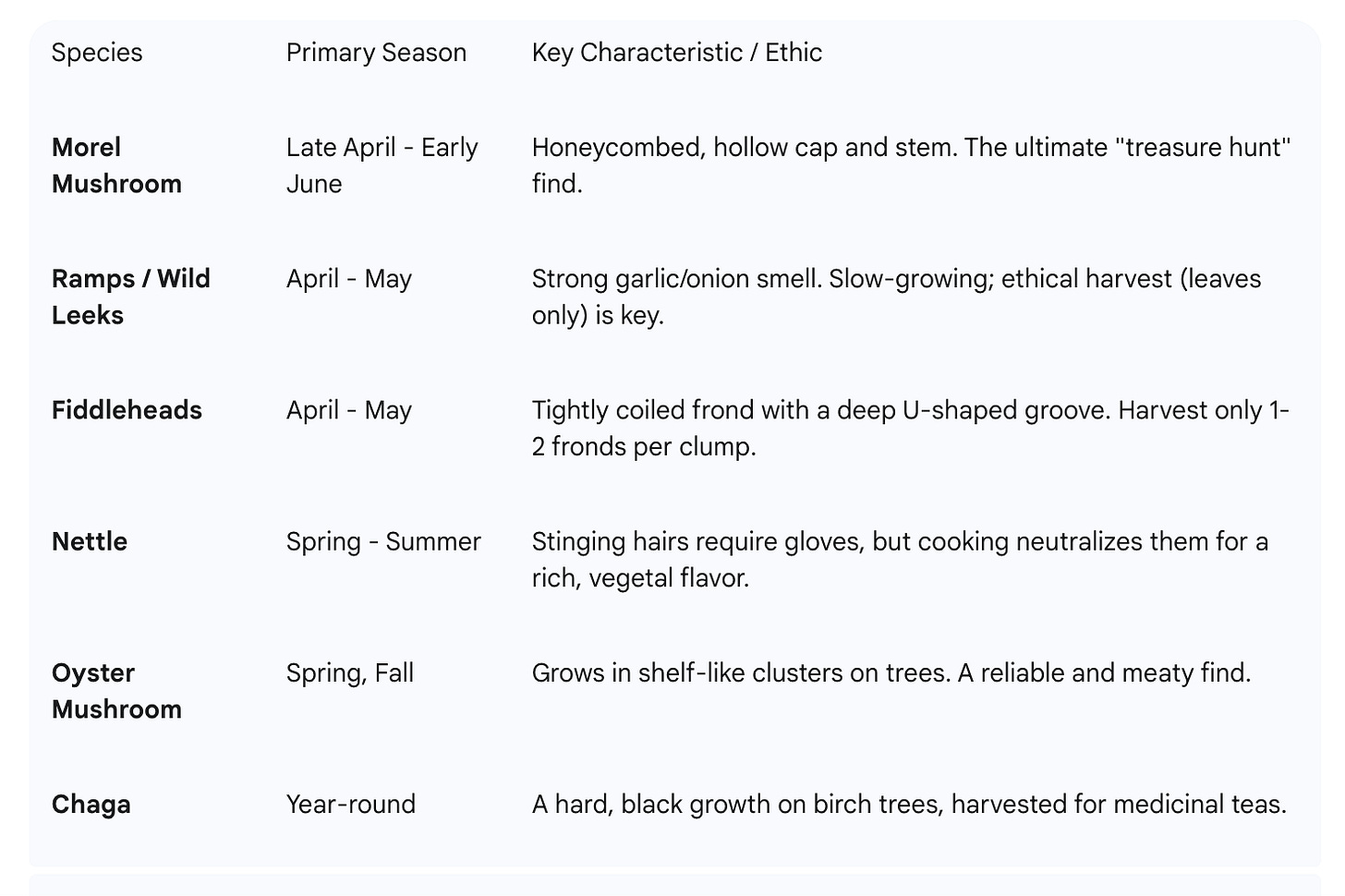

Our state's forests and fields are a generous, year-round pantry, but it's the spring that brings the most intense excitement. The season is defined by the hunt for the "holy trinity" of Vermont foraging: the fabled morel mushroom, the pungent ramp, and the fleeting fiddlehead. Their arrival marks the true start of the season and sends thousands of us into the woods.

Beyond this celebrated trio, the bounty continues. We find oyster mushrooms in the spring and fall, chaga on our birch trees year-round, and a host of wild greens like stinging nettle. It's a pantry that also includes an innovative approach to ecological management, as organizations like Audubon Vermont and researchers at UVM encourage us to turn invasive species like Japanese knotweed and garlic mustard into delicious resources.

A Web of Knowledge: The Forager's Network

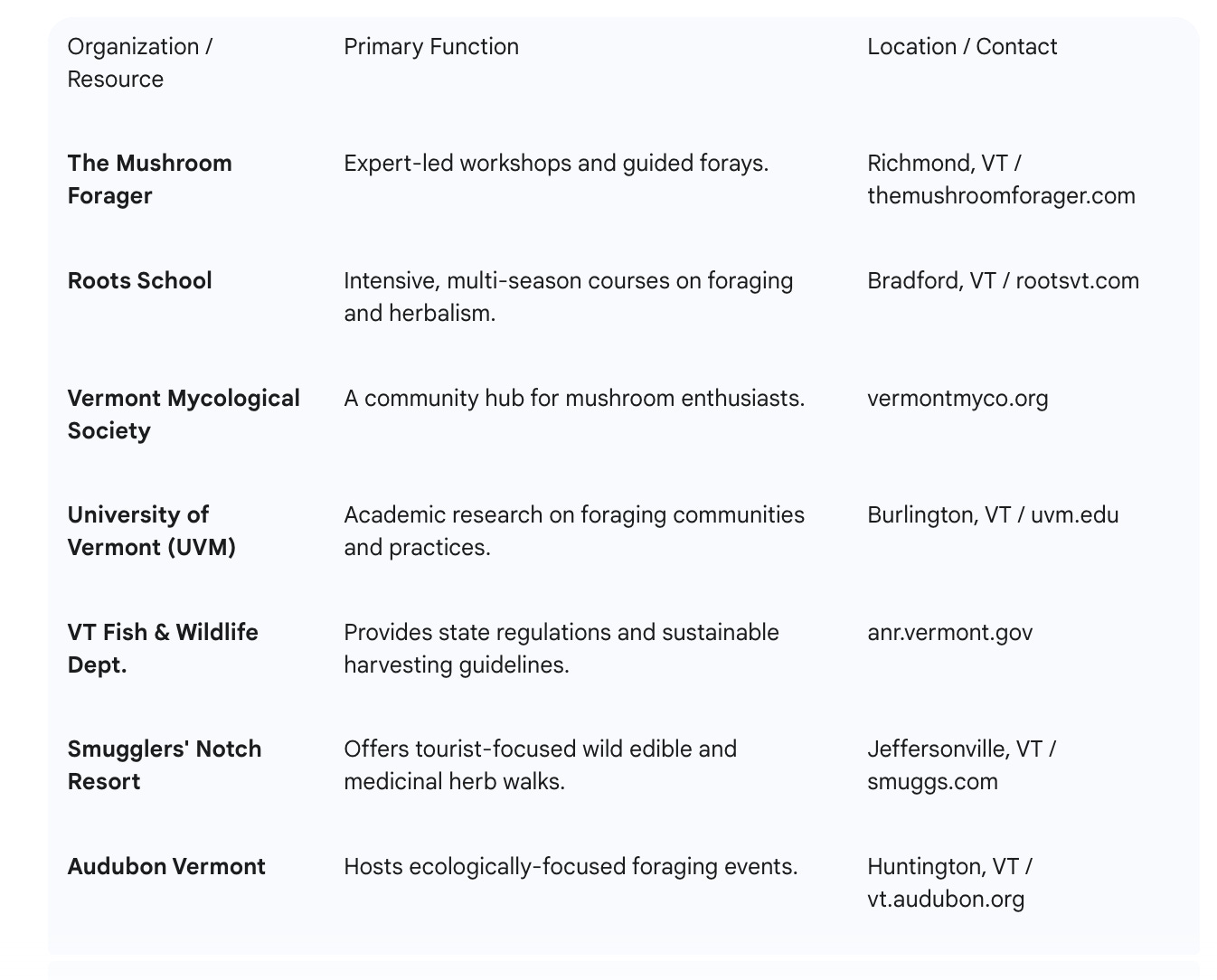

That 16,000-member Facebook group is the bustling town square of our foraging community, but the network of knowledge sharing runs much deeper, making Vermont's scene uniquely robust. We have a rich ecosystem for learning that caters to every level of interest.

This network blends the old with the new. The informal, oral tradition of learning from a mentor is still alive and well, but it's now supplemented by these massive online forums. What truly sets our state apart, however, is the depth of our formal educational infrastructure. It's a web that includes everything from expert-led workshops at places like Shelburne Farms to intensive, season-long programs for the most dedicated learners. This practice is woven directly into our tourism, economy, and even our academic institutions, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of interest and expertise that makes our foraging culture so exceptionally vibrant.

A Web of Knowledge: The Forager's Network

That 16,000-member Facebook group is the bustling town square of our foraging community, but the network of knowledge sharing runs much deeper, making Vermont's scene uniquely robust. We have a rich ecosystem for learning that caters to every level of interest.

This network blends the old with the new. The informal, oral tradition of learning from a mentor is still alive and well, but it's now supplemented by these massive online forums. What truly sets our state apart, however, is the depth of our formal educational infrastructure. It's a web that includes everything from expert-led workshops at places like Shelburne Farms to intensive, season-long programs for the most dedicated learners. This practice is woven directly into our tourism, economy, and even our academic institutions, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of interest and expertise that makes our foraging culture so exceptionally vibrant.

Now, if Vermont just had more truffles…