July's Flies Are Out in Force - Swating Them is Both Science and Art

In the 100 milliseconds it takes you to blink, a fly can detect a threat, calculate its trajectory, reposition its legs for takeoff, and launch itself in the opposite direction of the attack.

It’s a familiar Vermont story in July: the sun is out, the woods are calling, but so are the flies. That relentless buzzing and biting can turn a perfect summer day into a frustrating dance of frantic swatting. But what if you could trade that flailing for finesse? It turns out there's a science to swatting, and understanding your enemy is the first step to victory. With a little knowledge of biology and physics, you can go from being a fly's favorite target to a master swatter.

Know Your Adversary: The Flies of a Vermont Summer

The main culprits behind our summer misery belong to the Tabanidae family, better known as deer flies and horse flies. Here’s the rundown on these persistent pests:

It's the Females: Only female flies are out for blood, which they need to develop their eggs. The males are harmless nectar-feeders. You can even tell them apart: on males, the eyes are so large they touch, while females have a space between their eyes.

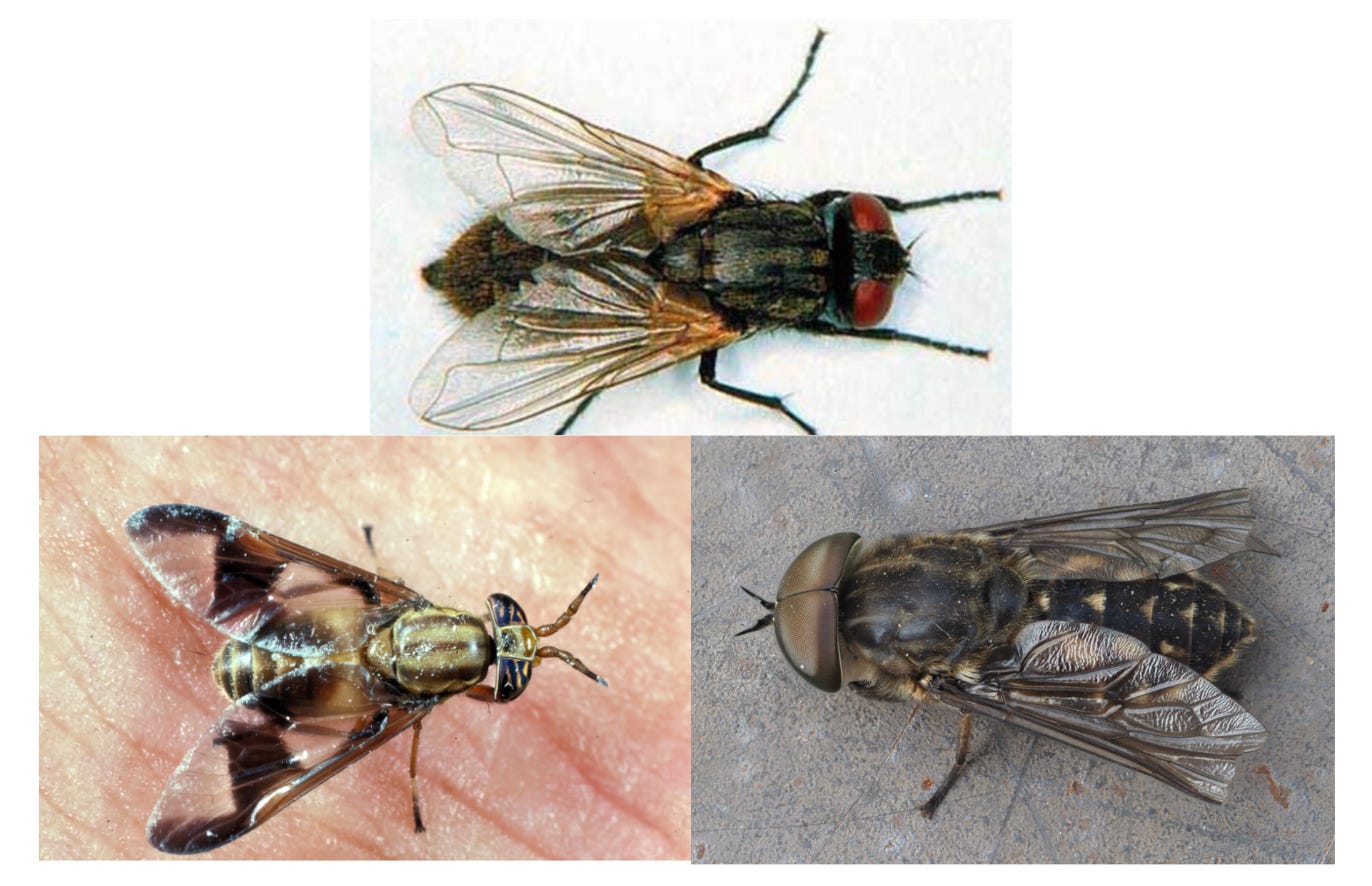

Deer Flies (Genus Chrysops): These are the smaller, more persistent ones, often with patterned wings and "psychedelic" eyes. They are notorious for circling your head and neck. We really don’t like them.

Horse Flies (Genus Tabanus): Larger, more robust, and sometimes called "B-52s," these flies have clear wings and solid-colored eyes. They tend to go for the legs and body. Their bite is particularly nasty because their blade-like mouthparts slash the skin to make blood pool. We really don’t like them either.

Peak Season: While the fly season runs from late spring until the first frost, early July is the peak for deer fly diversity, with their numbers continuing to climb all month. Vermont's abundant streams, ponds, and marshes are ideal breeding grounds for them.

Why Are They So Hard to Hit? A Fly's-Eye View

That feeling of futility when you swat and miss isn't your fault; it's a testament to the fly's incredible defense systems.

Slow-Motion Vision: A fly's large compound eyes are made of thousands of individual lenses, giving them a nearly 360-degree view. More importantly, they process information incredibly fast. While humans see about 60 images per second, a fly sees around 250. To them, your lightning-fast swat looks like it's moving in slow motion, giving them plenty of time to react.

Sensing the Air: Flies are covered in tiny hairs that can detect minute changes in air pressure. A solid object, like your hand or a hat, pushes a cushion of air in front of it. The fly feels this pressure wave nanoseconds before the object arrives, giving it a head start to escape.

The Escape Algorithm: In the 100 milliseconds it takes you to blink, a fly can detect a threat, calculate its trajectory, reposition its legs for takeoff, and launch itself in the opposite direction of the attack. Waving a hat around is the worst strategy—it’s a big, slow warning sign that also gives the fly a helpful puff of air to push it to safety.

The Art of the Swat: Technique is Everything

Forget brute force. A successful swat is about strategy and outsmarting the fly’s programming.

The Supreme Method: Aim Ahead: The single most effective technique is to aim slightly in front of the fly in the direction it's likely to flee. Since a fly almost always jumps away from a threat, your swat will intercept its escape route. If you swat from its right, aim for where its left will be.

The Slow Hand: A fly's vision is tuned to motion. It struggles to perceive very slow-moving objects. Try approaching a landed fly with your swatter in a very slow, deliberate motion. Once you're close, execute a quick, final flick of the wrist. The fly won't have time to register the threat and plan its escape.

Target Landed Flies: Your odds of success are highest when a fly is on a solid surface. A mid-air swat often just stuns it, requiring a follow-up blow.

Choose Your Weapon: The Swatter's Arsenal

The right tool is essential for an effective swat, and not all swatters are created equal. The key is defeating the "air cushion" effect.

The Classic Swatter: The simple, perforated flyswatter is a marvel of engineering. The holes in the grid are its most important feature, as they allow air to flow through, preventing the pressure wave that warns the fly. Its long, flexible handle acts as a lever, generating the high speed needed to overcome the fly's reaction time.

The Electric Racket: For mid-air combat and larger targets like horse flies, the electric swatter is the supreme weapon. Instead of relying on crushing force, it uses a high-voltage grid to electrocute the fly on contact with a satisfying "zap!" It's cleaner (no splatter) and highly effective against robust flies that a regular swatter might only stun. A continuous press of the button ensures even the toughest B-52 goes down for good.

From Frustration to Finesse

The summer war against Vermont's biting flies doesn’t have to be an exercise in frustration. By moving beyond instinct and embracing a more scientific approach, you can gain a clear advantage. The path to becoming a master swatter involves seeing the world as a fly does, anticipating its predictable escape plan, and choosing the right tool for the job. Better yet, by using their own hunting instincts against them with clever traps, you can reclaim your yard.

So, this July, don’t just flail. Arm yourself with knowledge, adopt a calculated strategy, and turn the tables on the Tabanid menace. You can replace the frantic waving with the quiet confidence that comes from mastering the sweet science of the swat.