Is the Resistance to Returning to the Office Just a Vermont Thing?

Vermont’s three-day hybrid requirement is not unusual compared to other states. A complicating factor is that Vermont still lacks office space for everyone.

When Vermont workers in the private sector were told by their bosses to return to the office after the pandemic, most simply did. Some companies embraced hybrid schedules, others brought people back full-time. Either way, the expectation was clear: if the employer required office attendance, employees complied or looked for another job.

So why has Governor Phil Scott’s plan to require state employees to work in-person three days a week drawn so much controversy in Vermont’s media? To understand, it helps to step back and look at how unusual widespread remote work really is in government, and what makes the state workforce different.

Remote Work Was Rare Before COVID

According to national workforce surveys, before 2020 fewer than half of state governments had any formal telework program. In local governments, that number was closer to one in five. Even the federal government, long considered more flexible, reported only about one-fifth of its workforce teleworking regularly in 2018. In Vermont, most state jobs were considered in-office by default.

It was only when COVID-19 forced offices to close that remote work became widespread. State governments around the country quickly adopted telework agreements. In the span of one year, the number of state and local agencies offering regular telework doubled. For many employees, working from home became the norm for the first time.

Vermont’s New Policy

Governor Scott’s administration has announced that starting December 1, most state employees will be required to work in the office at least three days per week. Officials say the change is about predictability, collaboration, and making services more accessible to the public. According to Administration Secretary Sarah Clark, employees will receive 90 days’ notice before any individual telework agreement is canceled.

For private-sector Vermonters who have been back at their desks for years, this looks like a standard hybrid schedule. But in state government, where many staff have worked remotely since 2020, it represents a shift away from what has become a comfortable routine.

Why State Employees Are Pushing Back

Union leaders with the Vermont State Employees’ Association argue the state cannot unilaterally change telework agreements without bargaining. According to the union, remote flexibility has improved morale, retention, and recruitment. Surveys of Vermont state workers show that more than 80 percent of partially remote employees believe telework improved their performance, and more than 90 percent say it improved work-life balance.

Another complicating factor is that Vermont still lacks office space for everyone. The July 2023 floods damaged 18 to 22 state buildings in Montpelier. According to state officials, many of those buildings remain under repair or awaiting upgrades, meaning some employees simply do not yet have offices to return to.

What Other States Are Doing

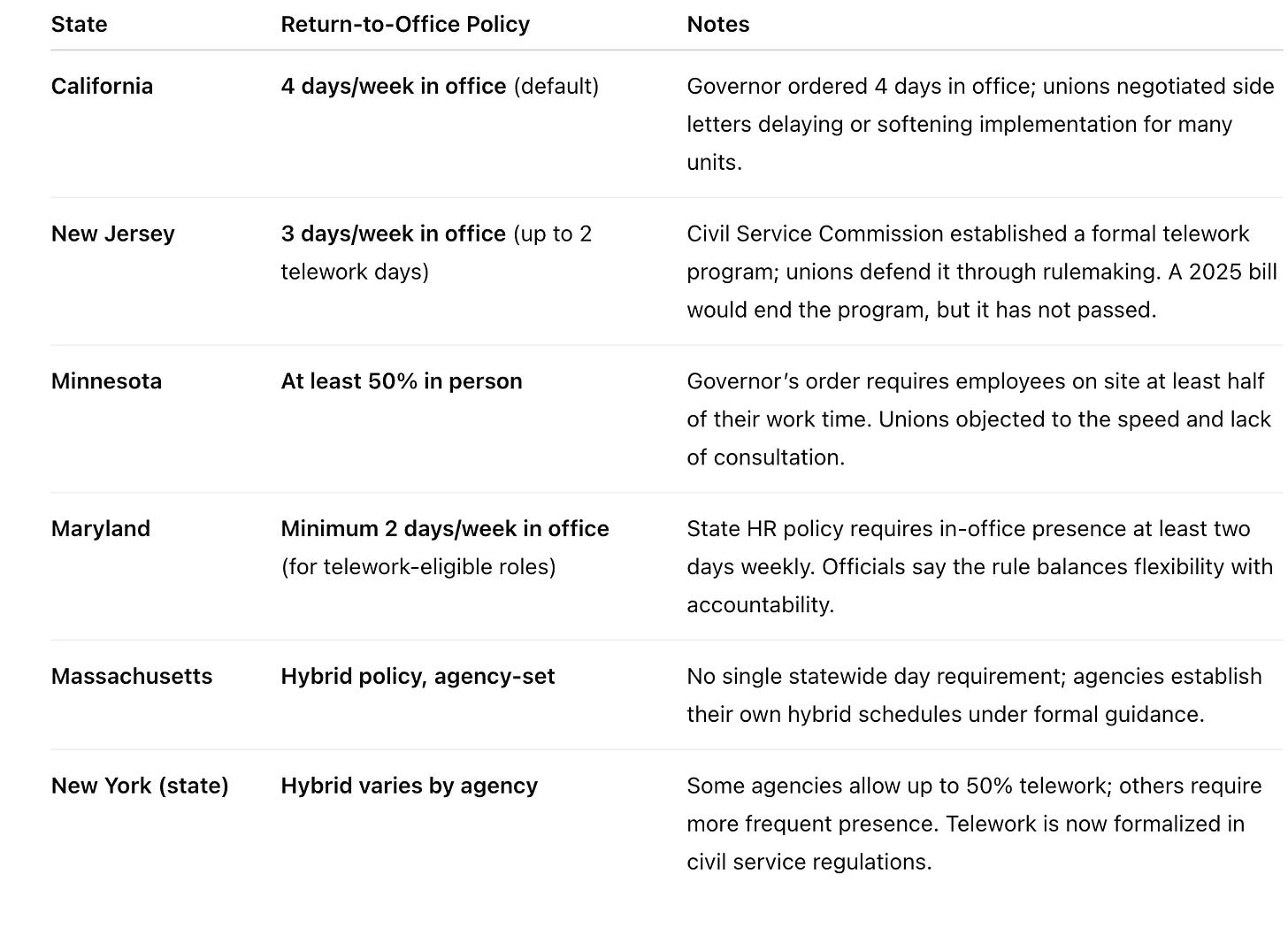

Vermont’s three-day hybrid requirement is not unusual compared to other states. California tried to mandate four days in the office this year, but unions negotiated side agreements delaying the order for years. Minnesota now requires employees to be in-person at least 50 percent of the time, a policy that unions there are also contesting. Texas, Ohio, and Oklahoma have gone further, requiring state employees to return to the office full-time.

Return to Office Policies in States Similar to Vermont

At the same time, states like Maryland and New Jersey have formalized hybrid schedules, typically requiring two or three in-office days. In Massachusetts and New York, agencies set their own policies rather than following a single statewide rule.

The common thread is that unions often challenge these policies through collective bargaining law. They argue that changes to work location are a mandatory subject of negotiation. In some cases, unions have pointed to side letters or telework agreements negotiated during the pandemic. In others, they have cited disability accommodations or state civil service rules. What unions have generally not argued is that COVID itself created a permanent right to remote work.

Private Sector vs. Public Sector

For Vermonters working in the private sector, the debate can feel foreign. By and large, private employers made return-to-office decisions years ago, and employees adjusted. The difference in state government is that union contracts, civil service rules, and the legacy of pandemic-era agreements give workers more leverage to resist changes.

That doesn’t mean state employees will remain remote forever. It does mean that in government, the process of getting back to the office involves more negotiation, more legal complexity, and more attention from the press.

The Takeaway

Before COVID, remote work in state government was rare. The pandemic changed that, and five years later, telework is still woven into how Vermont’s state employees do their jobs. Now, as the Scott administration pushes for a three-day office schedule, the resistance isn’t about whether offices matter—it’s about contracts, logistics, and who gets to decide.

For Vermonters watching from the private sector, it may look like state employees are fighting a battle long since settled elsewhere. In reality, Vermont’s situation mirrors a national pattern: the return-to-office debate is less about the number of days, and more about the rules of the workplace itself.