Iconic Vermont Brand Orvis Restructures, Facing a Shifting Outdoor World

Vermonters can be assured of one thing: the company has confirmed that its flagship retail store and headquarters in Manchester will remain open, preserving its historic home base.

Sunderland-based The Orvis Company, a pillar of Vermont’s outdoor identity for over 165 years, is making significant changes to navigate a rapidly evolving market. The company has announced layoffs, the closure of several U.S. stores, and the end of its historic mail-order catalog.

While these moves have caused concern, Vermonters can be assured of one thing: the company has confirmed that its flagship retail store and headquarters in Manchester will remain open, preserving its historic home base.

Orvis’s decision to become a “smaller and more agile business” is not based on a single issue, but rather a perfect storm of three critical factors that are reshaping the entire outdoor industry. Understanding them is key to understanding the future of this iconic brand.

Factor 1: From Lifestyle Hobbyist to Outdoor Sampler

The profile of the American outdoor enthusiast has fundamentally changed, shifting from a dedicated “lifestyle hobbyist” to a more casual and diverse “outdoor sampler.” This is perhaps the most significant challenge Orvis faces.

For decades, Orvis built its brand serving the lifestyle hobbyist—the person for whom fly fishing or wingshooting was a core part of their identity. This customer invested heavily in premium gear, participated dozens of times a year, and built their life around the sport. They were the “core” participants who, according to the Outdoor Industry Association, made up the predictable heart of the market.

Today, that dedicated enthusiast is being overtaken by a massive new wave of participants. A record 168.1 million Americans got outside in 2022, but these are largely “samplers.” Their engagement is broad, not necessarily deep. They might try fishing one weekend, hiking the next, and kayaking a month later. Their motivation is often social connection, wellness, or simply a change of scenery, rather than mastering a technical craft. The data reflects this: while total participation is at an all-time high, the average number of outings per person has fallen sharply by 11.4% in a single year.

This new “sampler” is also far more diverse. The OIA reports the fastest growth in participation is among Hispanic, Black, and female consumers—groups that heritage brands have historically struggled to reach. This shift creates a direct business dilemma for Orvis. The “sampler” is less likely to invest in a top-of-the-line, specialized fly rod. Serving this customer requires a different approach to product design, marketing, and price. Orvis now faces a market dominated by a consumer it wasn’t built for, forcing the difficult choice to refocus on its loyal, but shrinking, traditional base.

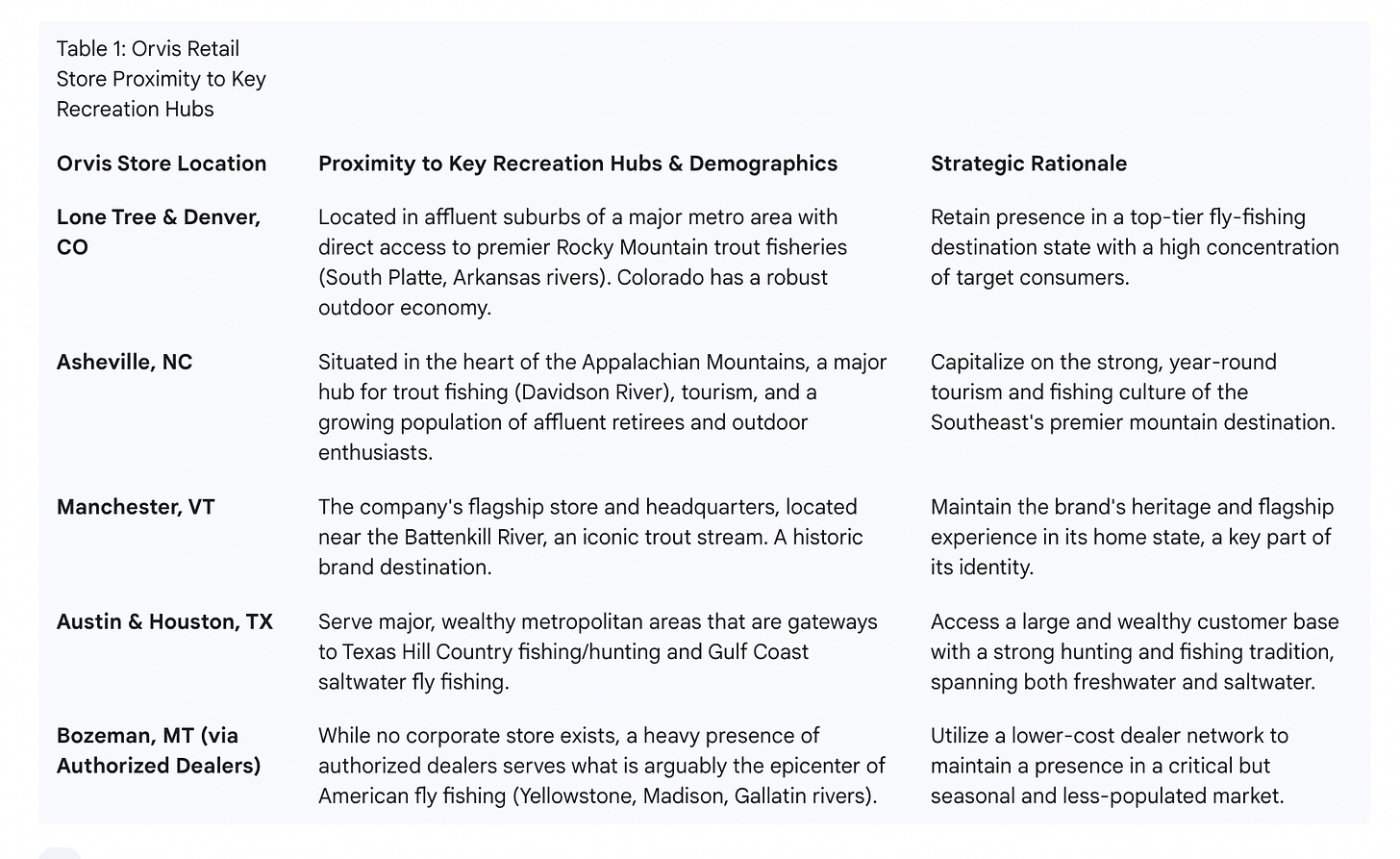

The store closures are a visible component of this consolidation. Confirmed closures include high-profile locations in major urban markets such as Chicago’s Magnificent Mile and Seattle, as well as stores in affluent areas like Arlington, Virginia, and outlet locations in Lake George and Pittsford, New York. An analysis of the remaining corporate-owned retail stores suggests a deliberate geographic strategy focused on maintaining a presence in key recreational hubs where their core activities are most robust.

Factor 2: The Tariff Squeeze

The most immediate economic pressure forcing Orvis’s hand has been international trade tariffs. While the brand is famous for its high-end, Vermont-made fly rods, a large portion of its revenue has come from a wide array of apparel, dog products, and home goods manufactured overseas.

Orvis President Simon Perkins stated directly that these tariffs have “disrupted our business model in ways we haven’t faced before.”

Essentially, the increased cost of importing these goods eroded their profitability. This financial pressure forced the company to abandon its diversified model and retreat to its most defensible and highest-margin core products: fly fishing and wingshooting gear, much of which is made domestically. The decision is less about branding and more about stark economic reality.

Factor 3: The Climate Change Threat

The most profound long-term threat to Orvis is the degradation of the natural world its sports depend on. Climate change poses an existential risk to the company’s core identity.

Threat to Fishing: Trout and salmon, the heart of fly fishing, require cold, clear water. According to scientific models cited by Defenders of Wildlife, these species could lose up to 42% of their stream habitat in the U.S. by 2090 due to rising water temperatures. A recent USGS study projected that warming waters in Montana alone could cost the state $192 million per year in lost fishing revenue.

Threat to Hunting: Warmer winters are altering bird migration. Waterfowl are stopping further north for the winter instead of flying down traditional flyways, a phenomenon called “short-stopping.” This directly impacts the quality and tradition of wingshooting in many parts of the country.

For a brand built on the promise of pristine rivers and wild landscapes, the shrinking of those very resources forces a strategic pivot. It reinforces the need to focus on its core sports and become a leader in the conservation efforts required to save them.

The Path Forward

Orvis is betting that by returning to its roots—focusing intensely on fly fishing and wingshooting—it can secure its future. The strategy is to solidify its position as the premier brand for the dedicated enthusiast.

The critical question remains: Can this leaner, more focused Orvis find a way to welcome the new, casual outdoor consumer? By closing stores in major cities and ending its catalog, it risks becoming less visible to the very people who represent the future of the market. The challenge ahead is to balance its celebrated heritage with the urgent need to connect with the next generation of outdoor enthusiasts.