Hay Farmers - VT Agriculture Agency Wants You to Cut a Little Higher

The Agency argues that increasing extreme weather, both flooding and droughts, makes now a good time to “raise the bar.”

Across the state, from the Champlain Valley to the Northeast Kingdom, a quiet but important conversation is happening in barns and on tractor seats. The Vermont Agency of Agriculture, backed by a mountain of research, is asking hay farmers to do something that sounds backward: harvest less of their crop.

The recommendation is to raise the cutting bar on their mowers, leaving 3 to 4 inches of stubble in the field instead of shaving it down to the dirt. To a non-farmer, it might seem trivial. To a farmer, that extra inch or two of stubble left behind is tons of potential feed or thousands of dollars of hay that they're being told to just leave in the field.

So, what’s the thinking behind this? And in a state where every dollar counts, will Vermont’s famously practical and independent farmers actually go for it?

Why Leave Good Forage Behind?

At its heart, this is about a trade-off between short-term gain and long-term health. The core of the issue comes down to how different hay plants store their energy.

Think of it like this: A legume like alfalfa is like a potato. It stores most of its energy for regrowth in a deep taproot, safe underground. You can cut it very low, and it will draw on its "root cellar" to grow back strong.

But the cool-season grasses that dominate Vermont's hayfields—species like orchardgrass and timothy—are different. They store their energy reserves in the lowest few inches of their stems, right above the ground. For them, a low cut is like raiding the pantry. It removes not only their leaves but also the very energy they need to recover.

When you repeatedly cut grass too low, you get a "cascade of consequences":

Slower Regrowth: The plant is stressed and takes longer to bounce back.

Weed Invasion: The weak, sparse grass can't compete, and weeds move in.

Stand Failure: Over a few seasons, the grass can simply die out, leaving a weedy, unproductive field.

On top of that, cutting higher means cleaner, better-quality feed. The lowest part of the stem is the most fibrous and least nutritious. Leaving it behind means the harvested hay is richer in protein and energy. It also drastically reduces the amount of soil—measured as ash content—that gets kicked up into the hay. Cows can't get energy from dirt, so cleaner forage is better forage.

The Vermont Reality: Rocks and Resilience

This isn't just a textbook theory. The recommendation to cut higher is especially critical given Vermont's unique challenges.

First, there’s our changing climate. We all know the new pattern: springs that are too wet followed by sudden summer droughts. That taller stubble left in the field acts like a mulch. It shades the soil, keeping it cooler and helping it hold onto precious moisture. This makes the hayfield more resilient and helps it survive those dry spells. When the rains do return, a healthier plant recovers faster.

Then there's the simple, bumpy reality of our fields. Vermont wasn't blessed with flat, rock-free soil. Our fields are bony. Trying to mow at 1.5 inches is a surefire way to hear the sickening crunch of a mower blade hitting a classic Vermont "pasture potato." Those rock strikes mean broken equipment, costly repairs, and downtime during the busiest time of year. Raising the bar is practical insurance. 🚜

The Economic Question: Does It Pencil Out? 💰

This is the make-or-break question. For dairy farmers, the math is compelling. The profitability of a dairy is driven by a metric called Income Over Feed Cost (IOFC). When a farm can feed its cows higher-quality forage, it can buy less expensive grain. That widens the profit margin on every gallon of milk sold.

While cutting higher means a small immediate reduction in tonnage, it provides a massive return by preventing much bigger future costs. The alternative—cutting low and degrading the stand—leads to a "hidden tax" of buying more grain, fixing equipment, and eventually, facing the huge expense of a complete field renovation, which can easily top $400 per acre.

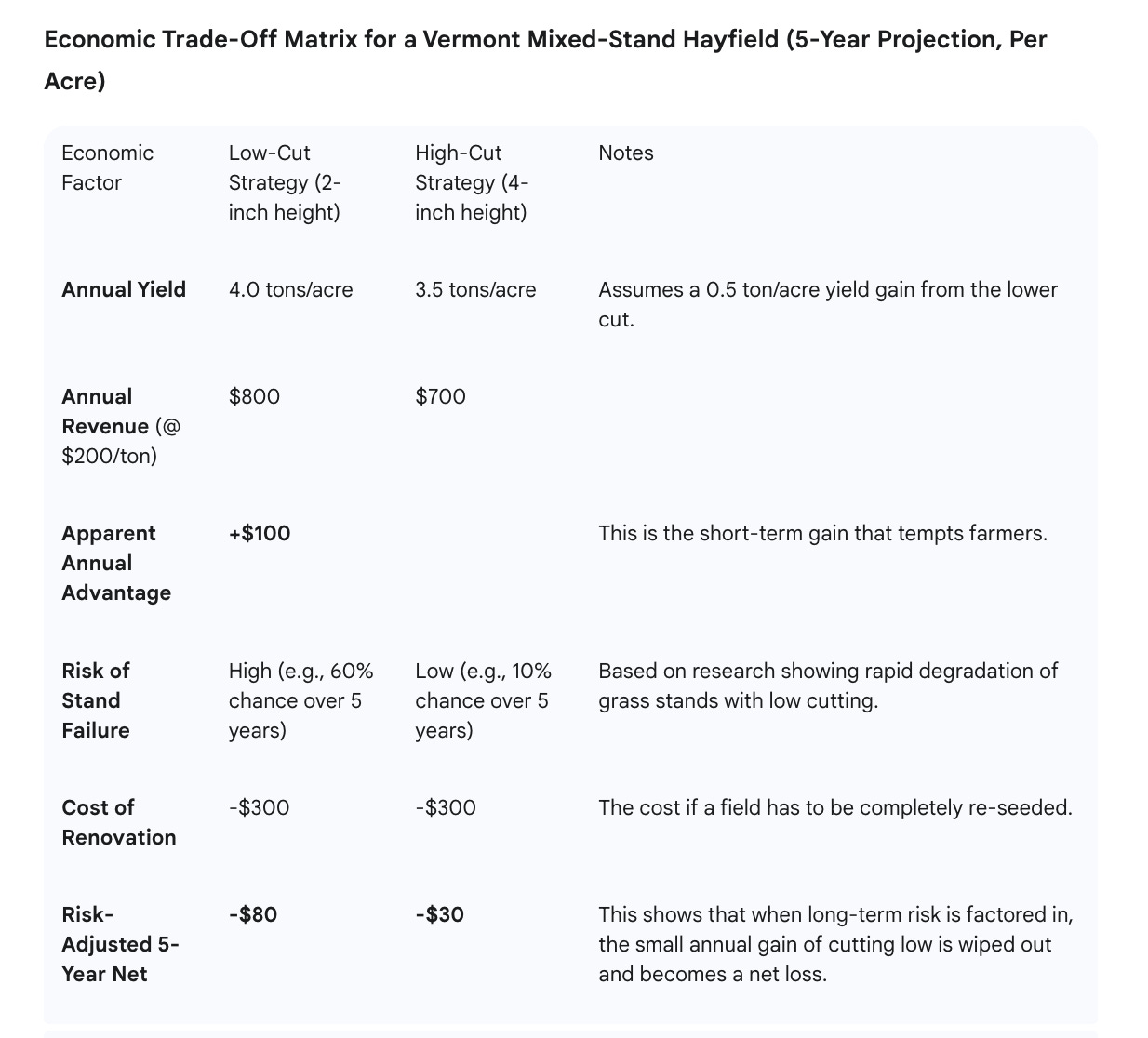

To put it in perspective, here is a simplified economic model for a typical Vermont mixed hayfield over five years.

Economic Trade-Off Matrix for a Vermont Mixed-Stand Hayfield (5-Year Projection, Per Acre)

This table shows that while "scalping" a field might look like a $100/acre gain each year, it's a gamble. Over the long haul, the high cost of a likely renovation makes it a losing proposition. The high-cut strategy is like paying a small insurance premium to protect against a catastrophic loss.

The Verdict: A Shift in Thinking 🤔

So, will Vermont farmers raise the bar?

For the state's large dairy farms, the evidence is overwhelming. With tight margins and a focus on efficiency, the move to a higher cut is not just good for the land; it's a smart business decision that improves feed quality and protects the farm’s most valuable asset. Many are likely already on board or will be soon.

For smaller, diversified farms or those selling cash hay, the decision might feel less urgent. But the underlying logic of protecting equipment from our rocky soils and ensuring the long-term health of their fields still holds true.

Ultimately, this isn't about giving up yield. It's about a shift in perspective. It's about seeing a healthy, resilient hayfield as the foundation of the entire farm enterprise. It's an investment in risk management, climate resilience, and long-term economic stability. For a state that values stewardship and pragmatism, raising the bar seems like a very Vermont thing to do.