Citing 135 Deaths and a $45 Million Annual Cost to Taxpayers, Governor Vetos Hotel/Motel Bill

“We can’t keep doing the same thing and expect different results,” Governor Phil Scott said.

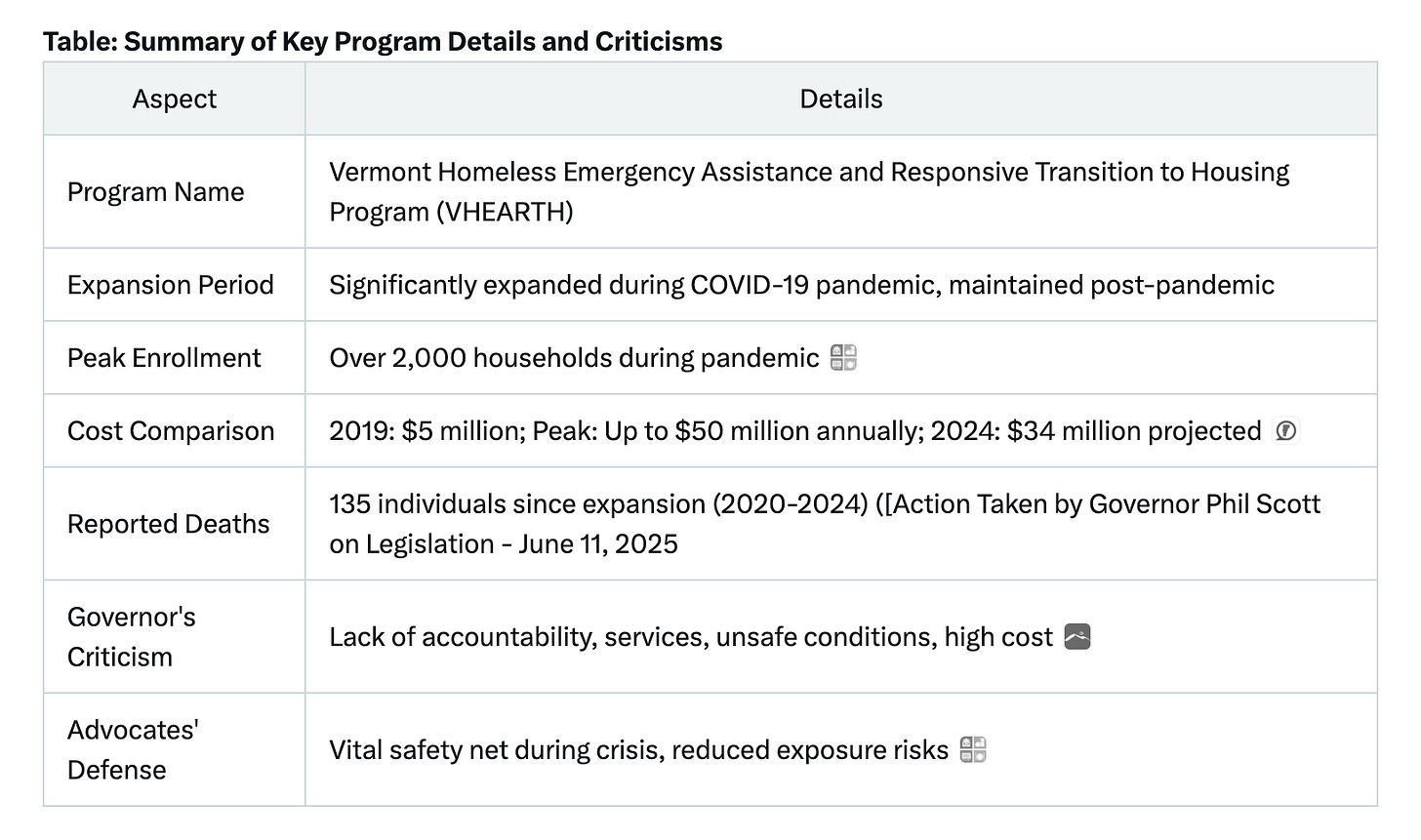

On June 11, 2025, Governor Phil Scott vetoed H.91, a bill designed to overhaul Vermont’s homelessness response by transitioning from the costly hotel/motel program to community-based solutions. The bill proposed spending over $45 million annually—exceeding last year’s $34 million budget—for a program extending through 2026, incorporating case management and permanent housing incentives but lacking clear cost-reduction measures. Scott’s veto, citing 135 deaths linked to the program, has intensified debate over its safety and effectiveness, raising questions about Vermont’s approach to its homelessness crisis.

A Program Born of Crisis

The Vermont Homeless Emergency Assistance and Responsive Transition to Housing Program, known as the hotel/motel program, expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic to shelter unhoused individuals in motels, reducing virus spread in crowded shelters. At its peak, it housed over 2,000 households, with costs ballooning to $50 million annually from $5 million in 2019. Unlike other states, Vermont maintained the program post-pandemic, making it a regional outlier and a lightning rod for criticism.

The 135 Deaths: What We Know

Governor Scott has repeatedly highlighted the 135 deaths among program participants from 2020 to 2024, arguing in his veto letter that “many of these deaths may have been prevented had there been more accountability and better engagement.” Detailed data on causes is scarce, as Vermont does not specifically track mortality among unhoused individuals. A 2024 Seven Days and Vermont Public report identified 82 deaths among Vermonters experiencing homelessness from 2021 to 2024, primarily from drug overdoses, vehicle accidents, and health conditions exacerbated by unstable living situations. Some of these likely overlap with the hotel program’s fatalities, but the precise causes remain unclear.

Advocates stress that homelessness itself increases mortality risk, with factors like exposure, untreated mental health issues, and substance use at play. “Blaming the program alone oversimplifies it,” said Sarah Phillips, director of the Upper Valley Haven. “Without motels, many would face worse risks on the streets.”

Critics, however, point to systemic flaws. Reports have documented poor motel conditions—mold, broken locks, and inadequate maintenance—posing health and safety risks. A 2023 VTDigger investigation detailed one participant’s struggle with a non-locking door and frequent hot water outages. The program’s practice of housing diverse groups, including families and individuals with substance use issues, in close quarters has also raised safety concerns.

Governor Scott’s Critique: Does It Hold Weight?

Scott contends that the program’s lack of wraparound services—mental health support, job training, or substance use treatment—leaves participants vulnerable. As a benefits program, it does not mandate engagement with social services, unlike traditional shelters. “We’re warehousing people without helping them move forward,” Scott said in a March 2025 press conference. He also criticized the mixing of vulnerable populations without oversight, creating unsafe environments.

Evidence supports some of Scott’s concerns. The absence of services may worsen mental health or substance use issues, potentially contributing to overdoses or untreated conditions. Substandard motel conditions could exacerbate health problems, and the lack of structured engagement contrasts with evidence-based programs prioritizing case management and housing transitions.

Still, the link to the 135 deaths is inferential without specific data. The opioid crisis, limited healthcare access, and homelessness itself complicate attribution. Advocates argue the program has saved lives by providing shelter. “It’s a stopgap, not a cure,” said Anne Sosin, a Dartmouth public health researcher. “Ending it without alternatives could do more harm.”

H.91 and the Veto: A Contentious Crossroads

H.91 aimed to reform the hotel program by shifting toward community-centered solutions, including enhanced case management and incentives for permanent housing. It proposed funding exceeding $45 million annually, a significant increase from 2024’s $34 million, to sustain the program through 2026. The bill sought to address criticisms by integrating services but fell short on cost containment and clear timelines for phasing out motel reliance.

Scott’s veto reflected his belief that H.91 entrenched a flawed system. He called for reforms like building shelter capacity and requiring participants to engage in work, training, or treatment to foster self-sufficiency. “We need real solutions, not more of the same,” he said, pointing to the program’s high cost and the 135 deaths as evidence of failure.

A Polarized Debate

The hotel program encapsulates Vermont’s struggle to address homelessness. Supporters view it as a vital safety net, especially during the pandemic, when it reduced exposure to disease and harsh weather. “For many, it’s a bed instead of a sidewalk,” Phillips said. Recent executive orders have ensured families and medically vulnerable individuals remain housed, underscoring its role for vulnerable groups.

Critics, including Scott, argue it’s a costly stopgap that fails to break the homelessness cycle. The program’s price tag strains state budgets, and its temporary nature offers little path to stability. Scott’s push for shelters with robust services and permanent housing investments reflects a broader call for systemic change.

Looking Ahead

The 135 deaths highlight the stakes of Vermont’s homelessness crisis. While Scott’s claim that the hotel program contributed to these tragedies has merit—given issues like unsafe conditions and lack of services—the full picture is nuanced. Homelessness itself is deadly, and the program’s role must be weighed against the risks of its absence.

With H.91’s veto, Vermont faces a pivotal moment. Consensus is growing that temporary measures like the hotel program are no substitute for affordable housing, mental health services, and evidence-based shelters. As lawmakers and advocates chart the path forward, the human cost of inaction remains stark.

“We can’t keep doing the same thing and expect different results,” Scott said. “It’s time to focus on what works—for Vermonters experiencing homelessness and the communities supporting them.”