Been for a Physical Lately? Their Intake Form Has Gotten A Lot More Personal

How Vermont’s healthcare system is collecting detailed demographic data—and what happens to it after you answer.

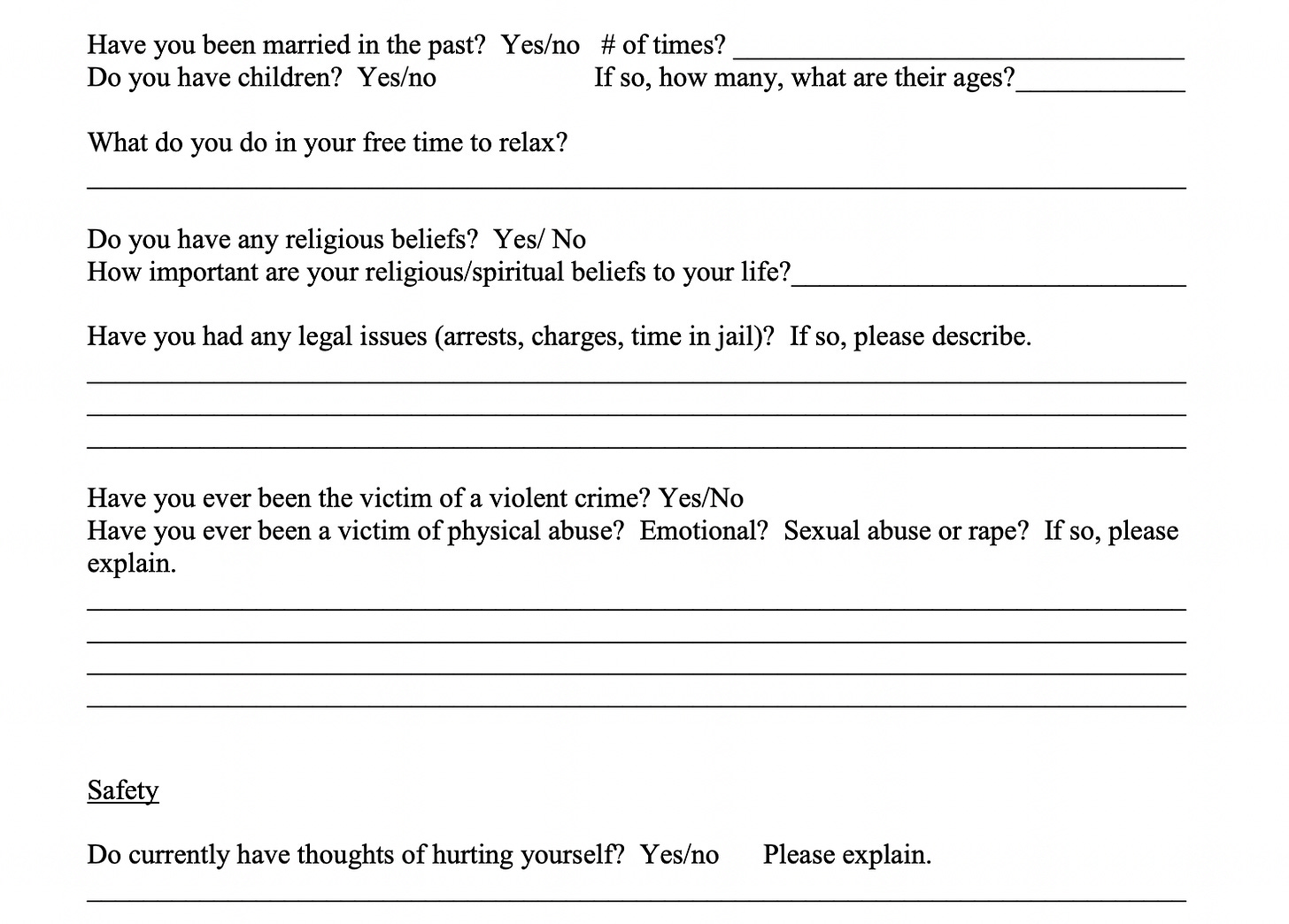

Vermont patients visiting their doctor for a routine checkup are encountering something new: intake forms that probe into personal territory that once seemed irrelevant to medical care. Questions about marital status, sexual orientation, gender identity, housing stability, and food security have become standard—part of a statewide shift in how healthcare providers collect and use patient information.

The trend isn’t unique to Vermont, but the state’s centralized health data infrastructure and small-town demographics create a distinct environment where these “invasive” questions, as some patients describe them, carry particular implications for privacy and research.

The Medical Case for Personal Questions

Healthcare providers and researchers defend these questions as medically necessary, arguing that demographic factors are powerful predictors of health outcomes. Research published in the Journal of the American Heart Association confirms that single mothers face significantly worse cardiovascular health profiles than partnered mothers, driven by higher rates of poverty, time scarcity, and chronic stress that manifest as elevated blood pressure and higher BMI.

When a physician asks “Are you married?”, they’re technically screening for a risk factor associated with cardiovascular disease. Similarly, questions about housing stability can identify patients at risk for complications during pregnancy or chronic disease management.

Dr. Jill Inderstrodt, a health policy researcher at Indiana University whose work relies on large-scale patient datasets, describes this as assembling a “giant puzzle of data” where each demographic answer provides crucial information for predicting conditions like preeclampsia—a life-threatening pregnancy complication.

Vermont’s Data Collection System

In Vermont, this data collection operates within a particularly comprehensive infrastructure. The University of Vermont Health Network, which includes Central Vermont Medical Center and affiliated practices throughout the state, has implemented what it calls “Inclusive Data Collection” policies.

Patients registering at UVM Health Network facilities encounter intake forms that go well beyond traditional insurance requirements. According to UVM Health Network guidance documents, the system collects gender identity categories including “Cisgender,” “Transgender,” “Nonbinary,” “Agender,” and “Genderqueer”; sexual orientation options spanning “Heterosexual,” “Gay,” “Lesbian,” “Bisexual,” “Asexual,” and “Pansexual”; and social determinants of health such as housing stability and food insecurity.

This information enters Epic electronic health record systems used across the UVM Health Network, making it accessible throughout the healthcare system’s multiple facilities.

Where Your Data Actually Goes

Once entered, patient data doesn’t stay at the local practice. Vermont operates one of the nation’s most centralized Health Information Exchanges through the nonprofit Vermont Information Technology Leaders (VITL). This system aggregates data from every hospital in Vermont, federally qualified health centers, and participating practices into a single longitudinal record for each Vermonter.

As of 2025, VITL connects 16 hospitals, 11 community health centers, and numerous pharmacies and laboratories across the state.

The critical detail: Vermont operates on an “opt-out” model following Act 53 of 2019. Unless patients take affirmative action to contact VITL and register an objection, their demographic and clinical data is automatically shared across the network. Reports indicate that 98.9% of Vermonters are currently sharing their data through this system.

The Research and Commercial Pipeline

Beyond direct patient care, this data feeds multiple streams. The UVM Health Network recently launched a “secure, collaborative research data enclave” specifically designed to “remove barriers” for University of Vermont researchers accessing clinical data for academic studies and “evidence-based policymaking.”

This means a patient visiting a UVM Health Network facility for a routine checkup simultaneously generates data that may be analyzed by researchers in Burlington studying rural health economics or maternal health outcomes.

The data can also enter commercial pipelines. While federal HIPAA regulations restrict the sale of identifiable patient data, the sale and licensing of “de-identified” datasets—with names and obvious identifiers removed—represents a multi-billion dollar industry involving analytics firms, pharmaceutical companies, and third-party vendors. Vermont’s own experience includes controversy over pharmaceutical companies purchasing prescriber data, an issue that reached the Supreme Court in 2011.

The Small-Town Privacy Problem

De-identification techniques that work in large cities face mathematical challenges in small Vermont communities. In privacy science, a dataset is considered safe when any individual record is indistinguishable from many others. A “35-year-old female with Type 2 diabetes” might match thousands of people in Boston; in a Vermont town of 3,600 residents, that same description combined with marital status and zip code might identify a single individual.

Research specifically examining Maine and Vermont hospital data has demonstrated these re-identification risks. Vermont’s small-town demographics create exactly the type of environment where standard de-identification may prove insufficient.

The risk isn’t merely theoretical. An incident at Southwestern Vermont Medical Center involved an employee accessing a specific patient’s record 106 times and her children’s records 94 times without legitimate medical reason. In VITL’s opt-out environment, every nurse, receptionist, and billing specialist at participating clinics across the state potentially has technical access to these records.

What the Data Isn’t Used For

While researchers emphasize population health benefits, patients should understand what the data collection doesn’t typically provide: immediate, individualized treatment modifications. A patient who reveals they’re unmarried generally won’t receive a tailored cardiovascular intervention during that visit. Instead, the data primarily supports retrospective research and population-level modeling—studies that may lead to public health programs or algorithmic tools developed years later.

The immediate users of demographic data are often billing departments using it for insurance risk adjustment and public health officials conducting surveillance, not the treating physician making clinical decisions during the appointment.

The Legislative Gap

Vermont patients looking to state consumer privacy laws for protection face a significant gap. The Vermont Data Privacy Act (H.121), which would have provided robust consumer data rights, was vetoed by Governor Phil Scott in June 2024. Even if enacted, the bill contained a “HIPAA exemption” explicitly excluding healthcare entities and protected health information from its provisions.

This leaves Vermont healthcare patients relying solely on federal HIPAA protections—a law enacted in 1996 that predates the era of big data, artificial intelligence, and statewide health information exchanges.

Patient Options

Vermont residents have limited but real options for controlling their data:

Patients can decline to answer demographic questions on intake forms that aren’t required for billing or direct care. UVM Health Network guidance indicates patients may select “Decline to Answer” for sensitive questions, though this may exclude them from certain outreach programs.

To opt out of VITL data sharing, Vermonters can call 1-888-980-1243 or submit a written request. This prevents routine access by providers statewide while maintaining emergency “break-the-glass” access for urgent care situations.

Patients using UVM Health Network’s MyChart portal can request an audit trail showing who has accessed their records—a right guaranteed under HIPAA.

However, opting out of VITL doesn’t prevent data sharing within the UVM Health Network itself, as all network facilities operate as a single “covered entity” under HIPAA. Restricting internal sharing requires filing a separate request with the network’s privacy officer, though such requests are rarely granted for treatment operations.

What Happens Next

Vermont’s healthcare data collection system continues to expand. The UVM Health Network’s research data enclave launched in 2024 represents increasing integration between clinical care and academic research. VITL’s participation rates—98.9% of Vermonters sharing data—suggest most residents either approve of the system or remain unaware of their opt-out rights.

The medical research community continues to demonstrate the value of comprehensive demographic data, from predicting pregnancy complications to identifying rare drug side effects. Yet the fundamental tension remains unresolved: data that saves lives at the population level can expose individual patients to privacy risks that scale inversely with town size.

Without new state privacy legislation specifically addressing healthcare data, and with VITL’s opt-out system firmly established, Vermont patients face a practical choice: accept the intake form’s increasingly personal questions as the price of participation in modern medical research, or take the affirmative steps necessary to limit their data’s circulation through the state’s interconnected health information systems.

The intake forms won’t be getting shorter.

Excellent deep dive on the small-town reidentificaton risk. The math here is crucial—standard deidentification breaks down when a "35-year-old female with Type 2 diabetes" becomes uniquely identifiable in a Vermont town of 3,600. I've worked on healthcare datasets where similar assumptions failed once you layered in even basic demographics. The 98.9% opt-in rate feels less like consent and more like inertia, especially when most pateints probably dunno the data flows to a research enclave or gets used for commercial analytics downstream.