Battle of the Giants: Understanding the Public Split Between Blue Cross and UVM Health Network

According to the Blue Cross campaign, a standard MRI scan at UVM Medical Center costs approximately $6,520 compared to $1,799 at an independent facility.

The landscape of Vermont healthcare is shifting beneath our feet. For decades, the relationship between the state’s largest insurer, BlueCross BlueShield of Vermont (BCBSVT), and its largest hospital system, the University of Vermont Health Network (UVMHN), was defined by private negotiation.

As of late 2025, that dynamic has dissolved into a public confrontation that places Vermont patients directly in the middle of a high-stakes financial dispute.

This week, BCBSVT launched a marketing campaign titled “VT Affordable Care.” The initiative explicitly urges Vermonters to bypass the state’s academic medical center in Burlington for certain services, citing massive price disparities. To understand what this means for your coverage and care, we must look beyond the marketing slogans and examine the financial realities driving this conflict.

The “VT Affordable Care” Campaign

The centerpiece of the insurer’s new strategy is a public website designed to highlight price differences between hospital-based care and independent providers. The campaign relies on “sticker shock” to drive its message home, utilizing specific data points to illustrate cost inefficiencies.

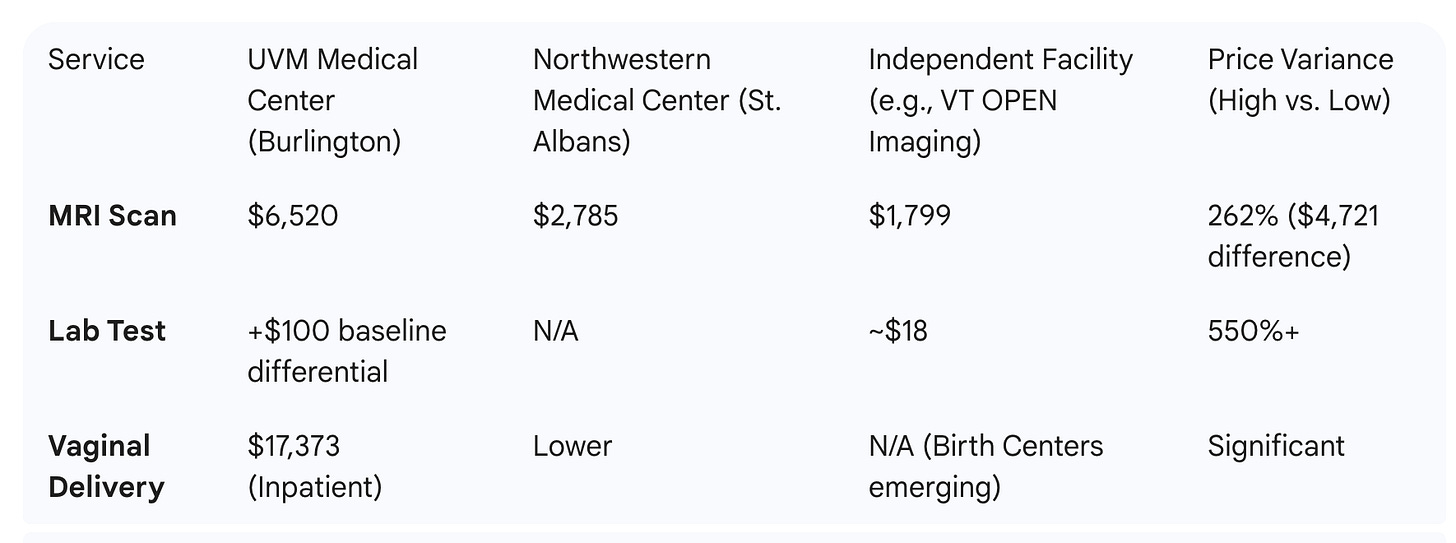

The insurer has released specific cost comparisons to illustrate why they are steering patients away from the academic medical center. The following table details the price variances highlighted by the campaign for common procedures:

According to the campaign data, a standard MRI scan at UVM Medical Center costs approximately $6,520. In contrast, the same scan at an independent facility, such as Vermont OPEN Imaging, is listed at $1,799—a difference of over $4,700. Similarly, the insurer highlights that lab tests can cost over $100 more at the hospital due to facility fees, compared to independent labs.

The campaign frames this not just as a saving for the insurer, but as a critical choice for patients, particularly those with high-deductible plans. By partnering with independent entities like Northwestern Medical Center in St. Albans and the Green Mountain Surgery Center, BCBSVT is attempting to steer patient volume away from the more expensive academic medical center to lower-cost community alternatives.

The Financial Engine: Why Now?

This aggressive move by BCBSVT is not arbitrary; it is a survival mechanism. The insurer is currently navigating a period of severe financial distress. In 2024, BCBSVT reported a deficit of $62.1 million, a loss that depleted its reserves to $58.4 million.

To put that in perspective, the insurer pays out roughly $35 million a week in medical claims. With reserves covering less than two weeks of operating costs, the company’s stability was threatened, leading to a credit rating downgrade by AM Best. Consequently, BCBSVT underwent a significant restructuring, becoming a subsidiary of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan to secure necessary capital and stability.

The “VT Affordable Care” campaign is a direct response to this solvency crisis. The insurer argues it can no longer afford to pay the rates charged by UVMHN without passing unsustainable premiums on to Vermont ratepayers.

The 19.6% Statistic

A major talking point of the new campaign is the claim that Vermonters spend a staggering portion of their income on healthcare. The campaign cites data showing that Vermonters spent 19.6% of their income on insurance premiums in 2025, ranking the state as the most expensive in the nation for premiums relative to income.

This figure is based on a WalletHub study comparing “Silver” plan premiums against median household income. For comparison, neighboring New Hampshire ranked as the lowest in the country, with residents spending only roughly 4% of their income on premiums.

It is important to interpret this number with nuance. For many employed Vermonters, employers cover a significant portion (often 70-80%) of that premium. Therefore, while the total cost of the policy may equal 19.6% of household income, the amount deducted directly from a paycheck is usually lower. However, economists argue that these high premiums still impact workers by suppressing wage growth.

The Hospital’s Position and Market Dynamics

The University of Vermont Health Network contends that simple price comparisons are misleading. As a Level 1 Trauma Center and an academic teaching hospital, UVMHN bears costs that independent imaging centers do not. They maintain expensive standby capabilities for burns, trauma, and complex neurosurgery—services that are often cross-subsidized by the higher margins on routine procedures like MRIs.

However, the relationship between the two entities has deteriorated significantly. During recent budget negotiations, state regulators noted a “simmering and ongoing adversarial relationship.” Reports surfaced that UVMHN had threatened to stop accepting Blue Cross insurance if their rate demands were not met, a move that would have left thousands of Vermonters without access to their primary doctors.

Legislative Changes Fueling the Shift

The insurer’s push for independent options has been bolstered by recent legislative action in Montpelier. In May 2025, the legislature passed Act 19 (S.18), which relates to the licensure of freestanding birth centers.

Crucially, this law exempts new birth centers from “Certificate of Need” reviews, removing a regulatory hurdle that often prevents new medical facilities from opening. The campaign highlights childbirth costs—citing inpatient deliveries at UVM costing over $17,000—and promotes these emerging independent birth centers as a viable, lower-cost alternative supported by the new state law.

What Happens Next

The launch of this campaign signals the end of private negotiation and the beginning of a market-based battle for patient volume.

Regulatory Intervention: The Green Mountain Care Board (GMCB) is closely monitoring this fracture. Independent liaisons have already suggested radical solutions to the pricing standoff, including potentially capping reimbursements at 500% of Medicare rates.

Consumer Behavior: The immediate question is whether Vermonters will change their habits. Will patients drive to St. Albans, Colchester, or West Lebanon for imaging to save money? If they do, UVMHN may face revenue shortfalls that could impact their budget requests for 2026.

Network Stability: If the financial bleeding at BCBSVT does not stop, or if UVMHN retaliates by narrowing its network, the state could face a crisis where insurance products and provider access no longer align.

For now, Vermont patients are being asked to become active consumers, comparing prices and “voting with their feet” in an effort to stabilize a system that regulators and insurers alike agree is on the precipice.

This experiment of creating a single bloated, uncompetitive health system, appears to have failed to produce any sold benefits. If uvm can not prove outcome or financial benefits the experiment has failed.

Further I would note that in my circle, most people drive to Dartmouth for specialized treatment, uvms treatment options are not perceived as on particular with Dartmouth.

How do we pull the plug on this failed experiment and open up opportunities for independent operators or adopt the Dartmouth model?