Across the Lake, In the Red: UVM Health’s Struggling New York Hospitals Raise Questions About Network’s Priorities

As the University of Vermont Health Network slashes expenses and braces for up to $185 million in cost reductions, new scrutiny is emerging over a lesser-known part of the system: its hospitals in upstate New York.

Acquired over the past decade, these rural facilities were brought into the network to expand access and stabilize care in the North Country. But a closer look reveals that the financial burden of these out-of-state assets has grown steadily — and today, they are a significant factor in the Network’s fiscal distress.

Three New York Hospitals, One Mounting Deficit

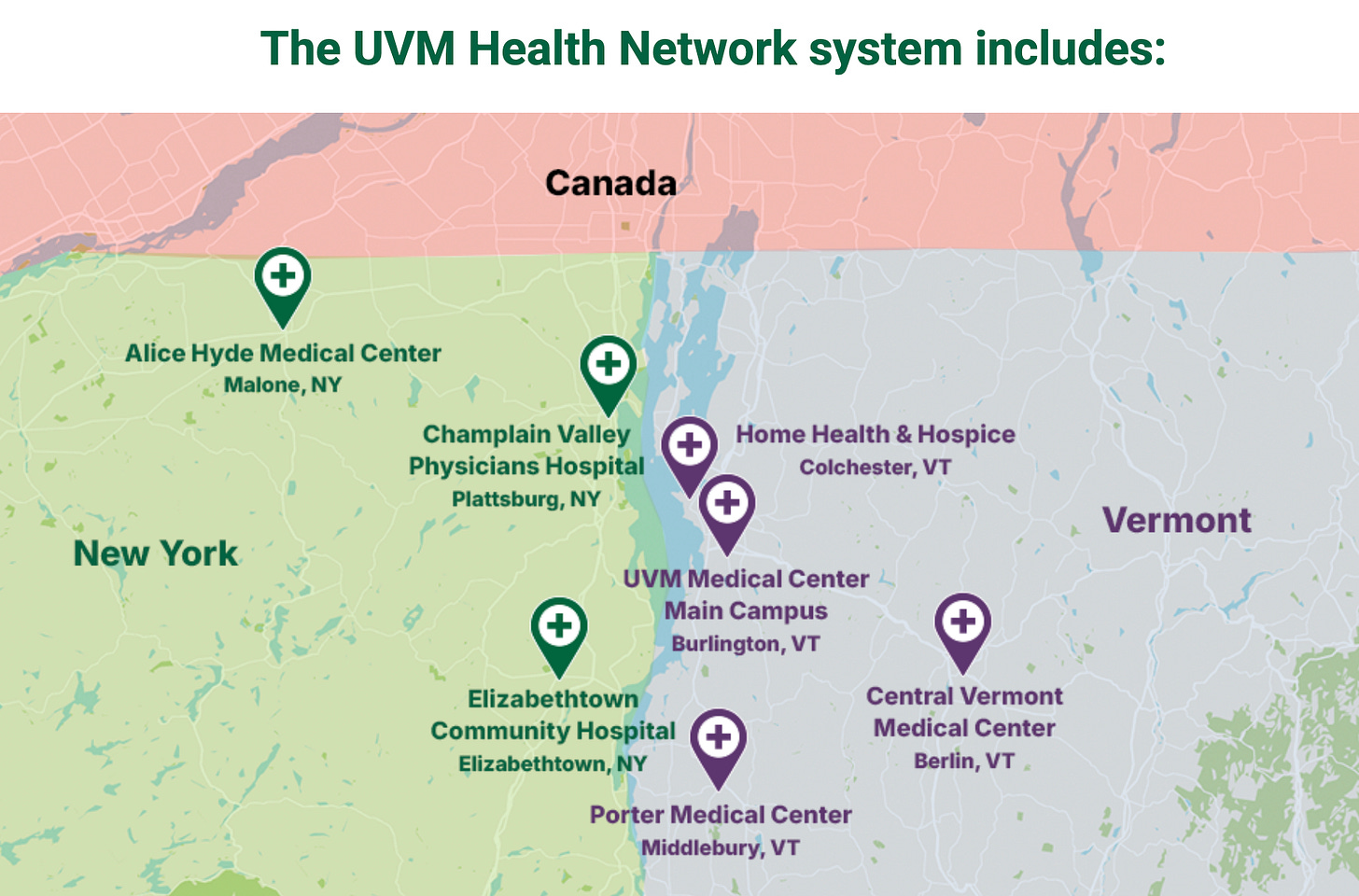

The UVM Health Network owns and operates three hospitals in northern New York: Champlain Valley Physicians Hospital (CVPH) in Plattsburgh, Alice Hyde Medical Center in Malone, and Elizabethtown Community Hospital (ECH). The first two — CVPH and ECH — joined the Network in 2013. Alice Hyde followed in 2016. These affiliations were announced with the promise of creating a seamless, bi-state system of care that would share resources and improve services for rural communities.

But the promise has come at a cost.

According to a 2023 financial analysis by former Vermont State Senator Christopher Pearson, now with the healthcare watchdog group Healthcare 911, UVM’s three New York hospitals collectively lost more than $62 million between 2014 and 2023, while the Network’s Vermont hospitals generated a $601 million surplus in the same period (“UVM Health Network Financial Overview,” Healthcare 911, Nov. 2023).

In 2023 alone, CVPH and Alice Hyde accounted for over $44 million in losses, or more than 80% of the Network’s total hospital operating deficit that year, according to a separate report submitted to the Green Mountain Care Board (UVMHN FY23 Hospital Budget Summary, Aug. 2023).

“This isn’t a small dip in the margin,” said Pearson. “These New York hospitals are a structural financial drag on the system. And it’s Vermont commercial insurance payers who are making up the difference.”

Cross-Border Subsidies and Quiet Transfers

For years, UVM Medical Center in Burlington — the Network’s academic flagship — has generated robust surpluses, mainly from private insurance payments. But internal financial disclosures reveal that cash from the Vermont side of the network has routinely been transferred to cover losses at its New York counterparts.

In 2017, UVMHN’s then-Chief Financial Officer Todd Keating confirmed that UVM Medical Center was making “cash infusions” to support Alice Hyde and CVPH when needed (VTDigger, Sept. 2017). That practice has continued, according to several Network budget presentations since.

CVPH — the largest of the New York hospitals — has consistently operated in the red. By FY2022, its annual operating deficit approached $30 million, and more recent figures place it near $40 million (GMCB Budget Hearings, 2023). Alice Hyde, a smaller hospital in Franklin County, also ran annual deficits in the range of $10–12 million, though its recent designation as a “Critical Access Hospital” (which boosts federal reimbursements) may slightly improve its outlook going forward (Alice Hyde Press Briefing, Oct. 2023).

In contrast, Elizabethtown Community Hospital — the smallest of the three and also a Critical Access Hospital — appears to operate close to break-even.

Strategic Vision or Mission Drift?

UVMHN leaders defend the New York acquisitions as consistent with their nonprofit mission.

“Our goal has always been to ensure that people in both Vermont and the North Country of New York can access quality care close to home,” said Dr. Stephen Leffler, president of UVM Medical Center, in a 2022 Network statement. “These communities would likely have lost essential services without a stable partner.”

Indeed, when Alice Hyde joined the Network in 2016, it was facing a nearly $3 million deficit and relying on traveling nurses to keep services running (Press-Republican, Jan. 2016). UVMHN helped it cut those monthly losses in half within a year, and brought specialty care from Burlington to its Malone campus, such as cardiology and orthopedics clinics (UVMHN Regional Integration Report, 2017).

Network officials also argue that shared clinical protocols and a unified electronic health record system have improved care coordination across the Vermont–New York border. Critically ill patients from Malone or Plattsburgh are often transferred to UVM Medical Center for advanced care.

The Cost to Vermonters

But critics say this expanded mission is coming at the expense of Vermont’s own healthcare stability.

“The average Vermonter doesn’t know their premiums are propping up hospitals in a different state,” said Pearson. “And it’s not clear the Network has delivered the efficiencies it promised.”

In fact, since the formation of UVMHN, administrative staff across its hospitals have grown by over 30%, outpacing growth in clinical staff, according to data reviewed by the Green Mountain Care Board in 2023 (GMCB Staff Analysis: UVMHN Budget Trends).

Meanwhile, access to care in Vermont has tightened. Wait times at UVM Medical Center have grown, several outpatient services have been consolidated or closed, and the Network recently announced layoffs, frozen positions, and a halt to executive bonuses — though base pay remains in the millions for its top leaders (Seven Days, July 2025).

Could Selling the New York Hospitals Help?

Financially, divesting from Alice Hyde and CVPH could dramatically improve UVMHN’s bottom line — at least on paper. By shedding their operating losses, the Network could show better margins and reduce pressure to raise rates in Vermont.

But the solution isn’t that simple.

“These hospitals are struggling not because of mismanagement, but because of demographics and payer mix,” said Dr. Sunny Eappen, CEO of UVMHN, in an interview with Vermont Public in March. “They serve older, poorer populations with high Medicaid and Medicare volumes, and reimbursement doesn’t cover the cost of care.”

That’s a challenge for nearly every rural hospital in the country. And there’s no guarantee that another system — or the state of New York — would take over facilities like Alice Hyde or CVPH if UVMHN exited.

“Walking away could leave whole regions without essential services,” said Eappen.

Some see the Network’s dual-state footprint as a long-term strength. With the right reforms — such as increasing federal payments or trimming administrative costs — UVMHN could stabilize its finances without downsizing.

But for many Vermonters, the question remains: In a time of crisis, should the University of Vermont’s flagship health system be anchoring hospitals across state lines? Or should it focus on making care more accessible and affordable at home?

“It’s not about us versus them,” said one Burlington nurse who asked not to be named. “But it sure feels like Vermont is picking up the tab.”

I am new to Vermont Compass. The articles are well written and informative. I read on the About page why there is no byline, but the reasoning doesn’t satisfy. Please consider amending the no byline policy.