A Nine-Year-Old from Ludlow Bought the First Share in a New Ski Area 70 Years Ago—It Was Named Okemo

The seeds of Okemo were planted during the Great Depression, when State Forester Perry Merrill—often called the “father of Vermont skiing”—pushed to create recreational forests.

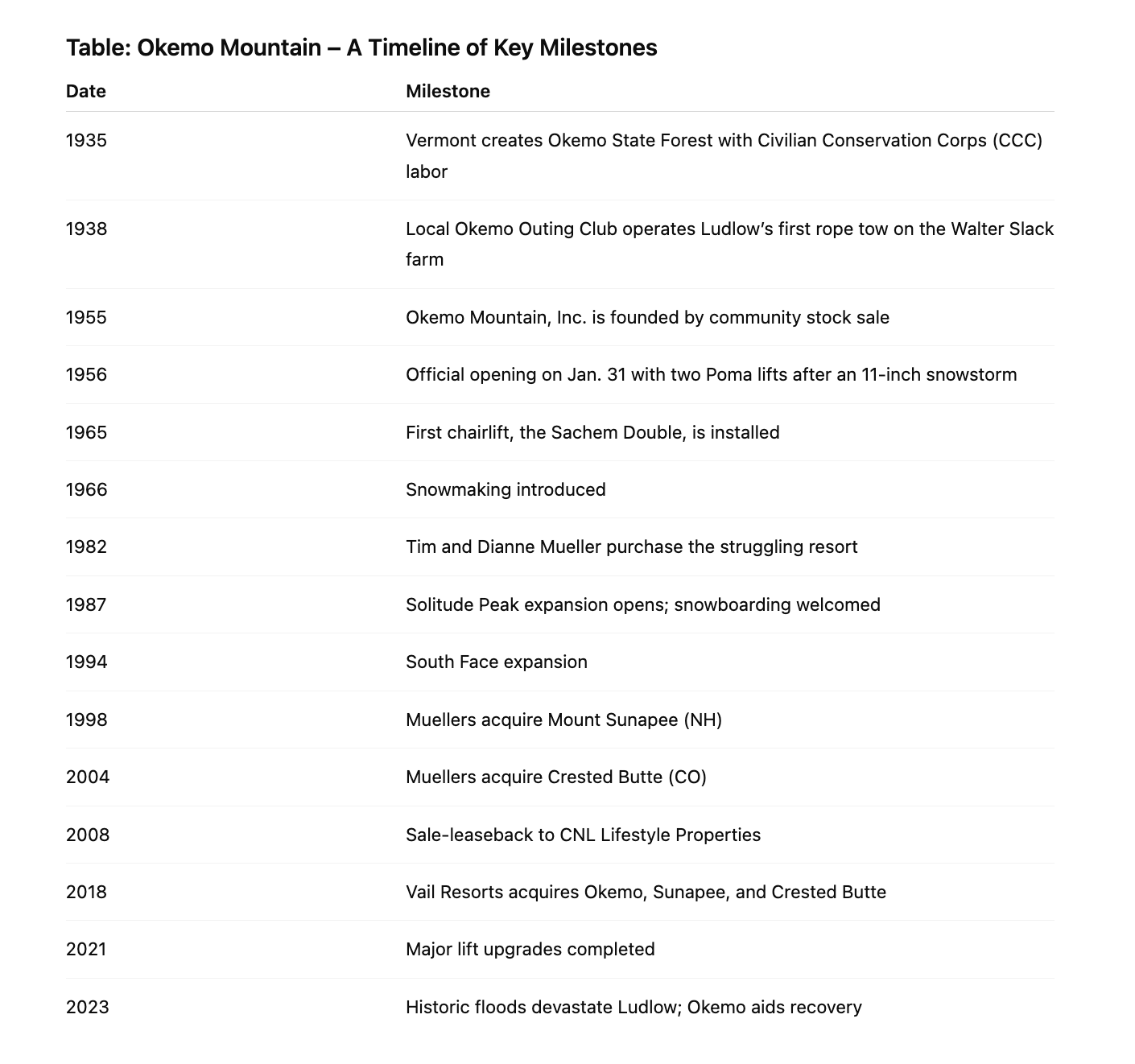

Seventy years ago, on a wing, a prayer, and a last-minute blanket of snow, a small Vermont ski hill sputtered to life. Built not by tycoons but by townspeople with ten-dollar shares and borrowed trucks, Okemo Mountain Resort in Ludlow has grown into one of the most recognizable names in Eastern skiing.

Its story unfolds in three acts: first, the grassroots creation of a community-owned ski area; second, the renaissance of a struggling hill under a “mom-and-pop” couple who turned it into a national powerhouse; and finally, its current role as a global corporate asset under Vail Resorts. Each era has left its own mark, and together they form a uniquely Vermont story of resilience, ambition, and identity.

Part I: The Community’s Mountain (1935–1956)

A Vision in the Green Mountains

The seeds of Okemo were planted during the Great Depression, when State Forester Perry Merrill—often called the “father of Vermont skiing”—pushed to create recreational forests. According to state records, Vermont purchased 4,000 acres on Ludlow Mountain in 1935 for $9,250, about $2.31 per acre. Critics in Montpelier called it “frivolous spending” in lean times, but Merrill pressed ahead with Civilian Conservation Corps crews who carved trails, built road, and left behind the infrastructure that would later serve skiing.

Meanwhile, locals were impatient. In 1938, the Okemo Outing Club installed Ludlow’s first rope tow on the Walter Slack farm. It wasn’t much, but it proved that the town wanted skiing—and was willing to make it happen.

“For the Price of a Share”

By 1955, townspeople decided to take matters into their own hands. On January 7, they formed Okemo Mountain, Inc., funded entirely by community stock sales at $10 a share. According to New England Ski History, even children participated—one of the very first shareholders was a nine-year-old Ludlow boy who, after more research, was determined to be a girl.

A local lumber mill owner hauled the new French-made Pomalifts from Boston at no charge. And in the fall of 1955, according to early accounts, the founders themselves cleared the first trails by hand. It was a community project in the truest sense.

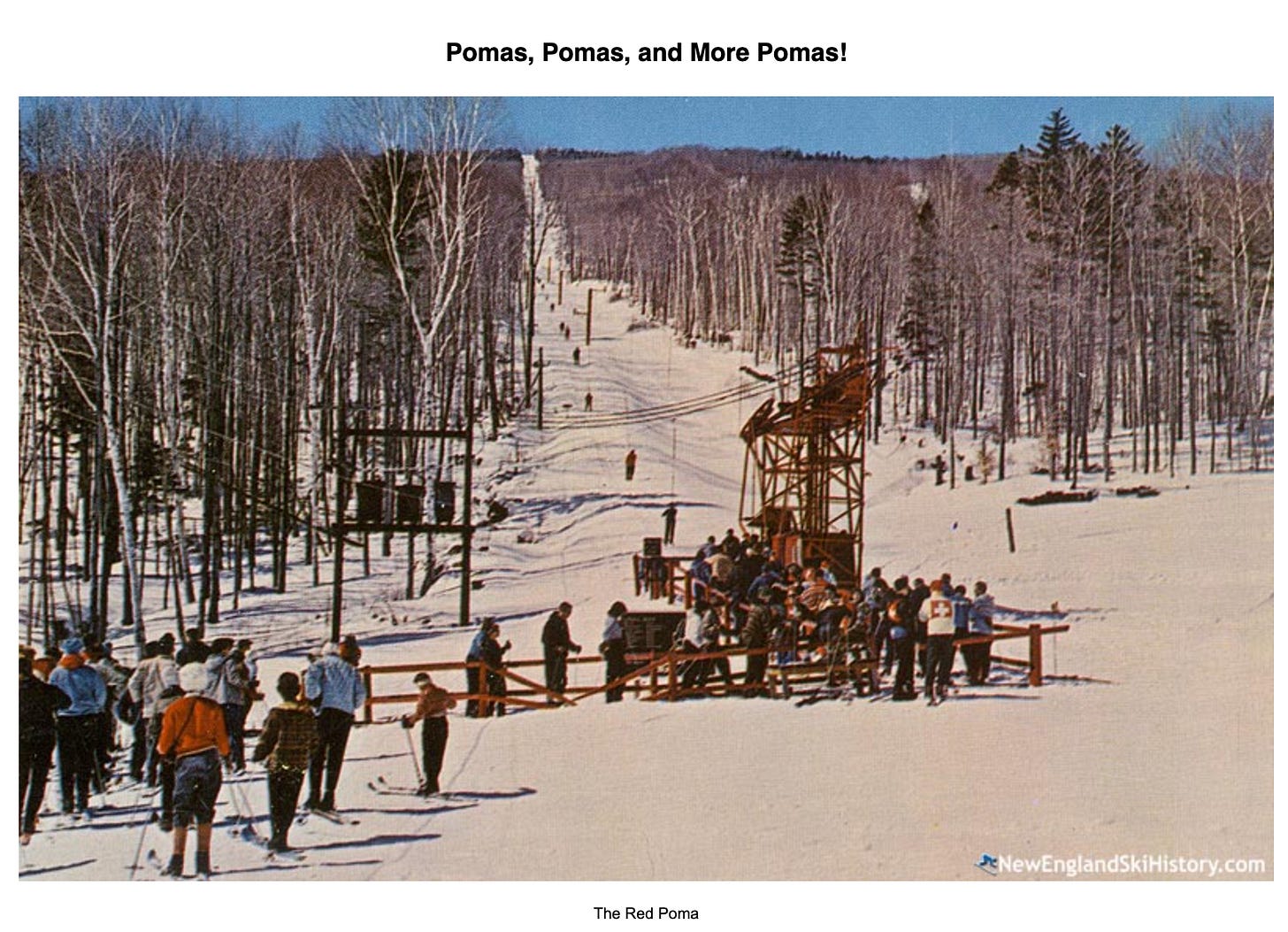

When the mountain finally opened on January 31, 1956—after a desperate 11-inch storm saved the snowless slopes—the dream had become real. Rides on the long summit Poma cost 60 cents, but for locals who had invested, it was priceless.

Part II: The Poma Years and the Precipice (1956–1981)

For its first decade, Okemo was known as the “Poma mountain.” While other Vermont resorts built chairlifts, Okemo expanded its platter lifts. This frugality kept it alive but also earned a reputation as outdated.

The 1960s brought snowmaking (1966) and grooming machines, but by the 1970s, hard times hit. Floods, fires, and competition battered the resort. Then came the disastrous winter of 1979–80, when little snow fell across New England. According to industry accounts, skier visits collapsed and Okemo nearly went bankrupt. By 1982, the board decided to sell rather than close—setting the stage for its rebirth.

Part III: The Mueller Renaissance (1982–2018)

A Gamble in Paint and Snow

Tim and Dianne Mueller bought Okemo on August 2, 1982, with everything on the line. They couldn’t afford big projects at first, so Diane hand-painted signs herself to freshen the place up. “Mom-and-pop” wasn’t just a label—it was reality.

When snow failed to arrive until mid-January that first winter, the Muellers fired up snowmaking, opening six trails by Christmas. This cemented their philosophy: skiing could no longer depend on the weather.

Building the “Okemo Difference”

Over 36 years, the Muellers poured over $100 million into snowmaking and grooming. By the mid-1990s, Okemo had 98% snowmaking coverage, guaranteeing corduroy skiing even in dry winters. In 1995, when natural snowfall barely reached 100 inches, Okemo still drew 480,000 skiers, while competitors suffered steep losses.

The Muellers also expanded terrain—opening Solitude Peak in 1987, South Face in 1994, and the Jackson Gore village by 2004. They welcomed snowboarders early (1987), invested in family programs, and reinvested condo profits back into the mountain.

By the late 2000s, Okemo was ranked among the top two resorts in the East by skier visits.

Part IV: The Vail Era and a New Identity (2018–Present)

The Epic Arrives

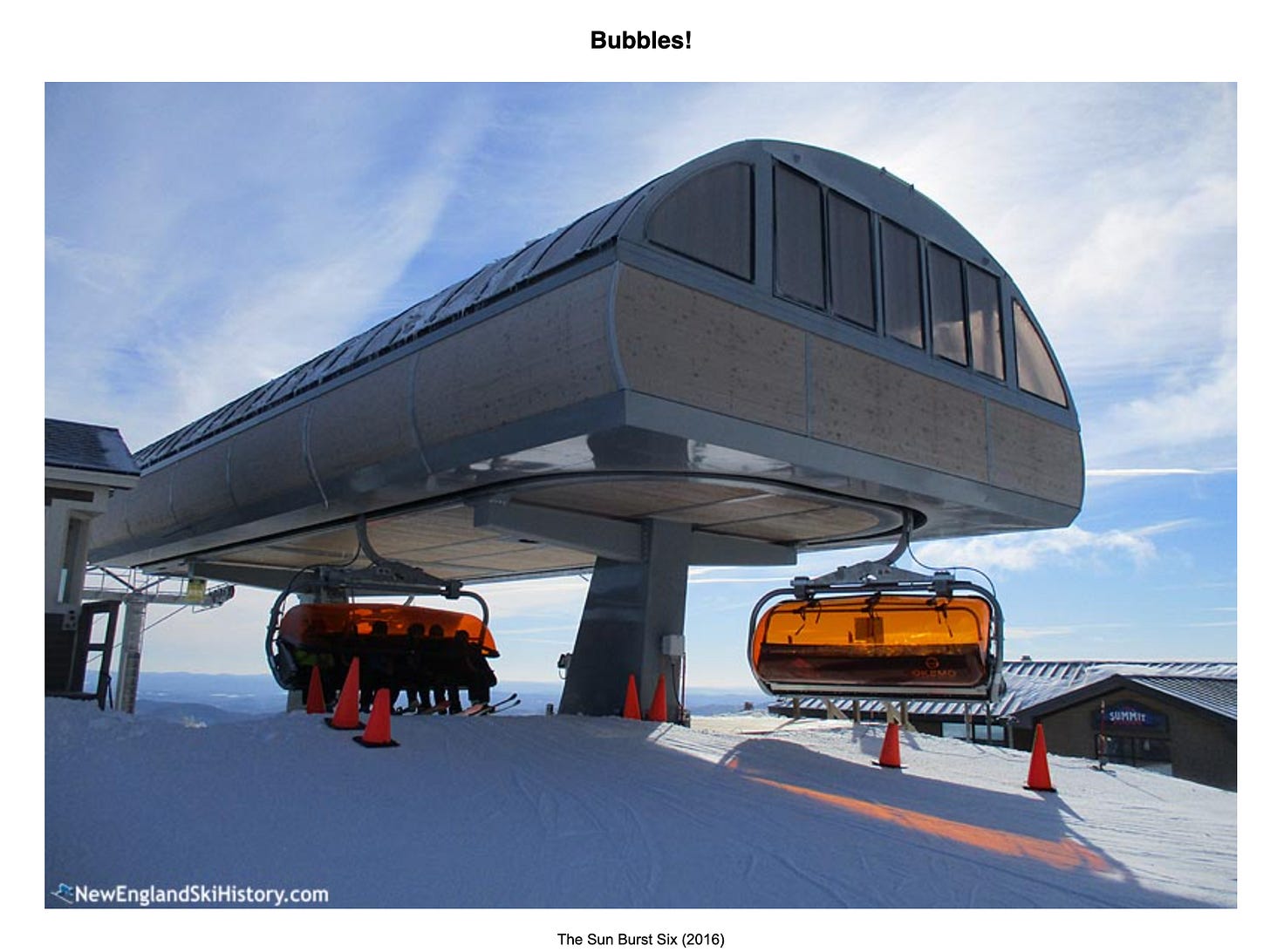

On September 27, 2018, Vail Resorts acquired Okemo, folding it into its global Epic Pass network. The move brought scale, efficiency, and major investments—new high-speed lifts in 2021 among them.

Today, skiers ride the Quantum Six, a heated-seat bubble lift, a long way from the clunky Poma platters of 1956. The leap from rope to bubble tells the story of the industry itself.

Corporate Soul or Soulless?

According to skier surveys and reviews, Vail’s ownership brought mixed feelings. The Epic Pass offers huge value, but some longtime visitors lament the loss of the Mueller-era “family feel.” Complaints about food prices, lift operations, and “corporate culture” swirl. Yet Vail has also brought sustainability goals and affordable housing projects for employees, signaling the responsibilities of a global operator.

Part V: The Enduring Soul of Okemo

Ludlow’s Lifeline

Okemo has always been tied to Ludlow. According to town records, the Jackson Gore expansion even funded the Ludlow Enterprise Fund, which built civic projects like a new police station.

That bond was tested in July 2023, when floods devastated the town. Okemo opened its inn to house displaced residents, cooked meals, and sent machinery to clear debris. Once again, the fates of mountain and town proved inseparable.

What’s in a Name?

Before it was Okemo, the peak was known as Glitchever Mountain. The adopted name “Okemo” has disputed origins—some say “All Come Home,” others suggest meanings ranging from “chieftain” to “a louse.” But whatever the linguistics, 70 years of skiing have given “Okemo” a meaning of its own: family, snowmaking, resilience, and Vermont.

Conclusion: The Next Run

Okemo’s journey from ten-dollar shares to corporate consolidation mirrors the story of American skiing itself. Each chapter—community, family, corporation—has added something lasting.

The challenge ahead is balance: preserving the mountain’s soul while benefiting from global scale. Whether it can keep that balance will define Okemo’s next seventy years.